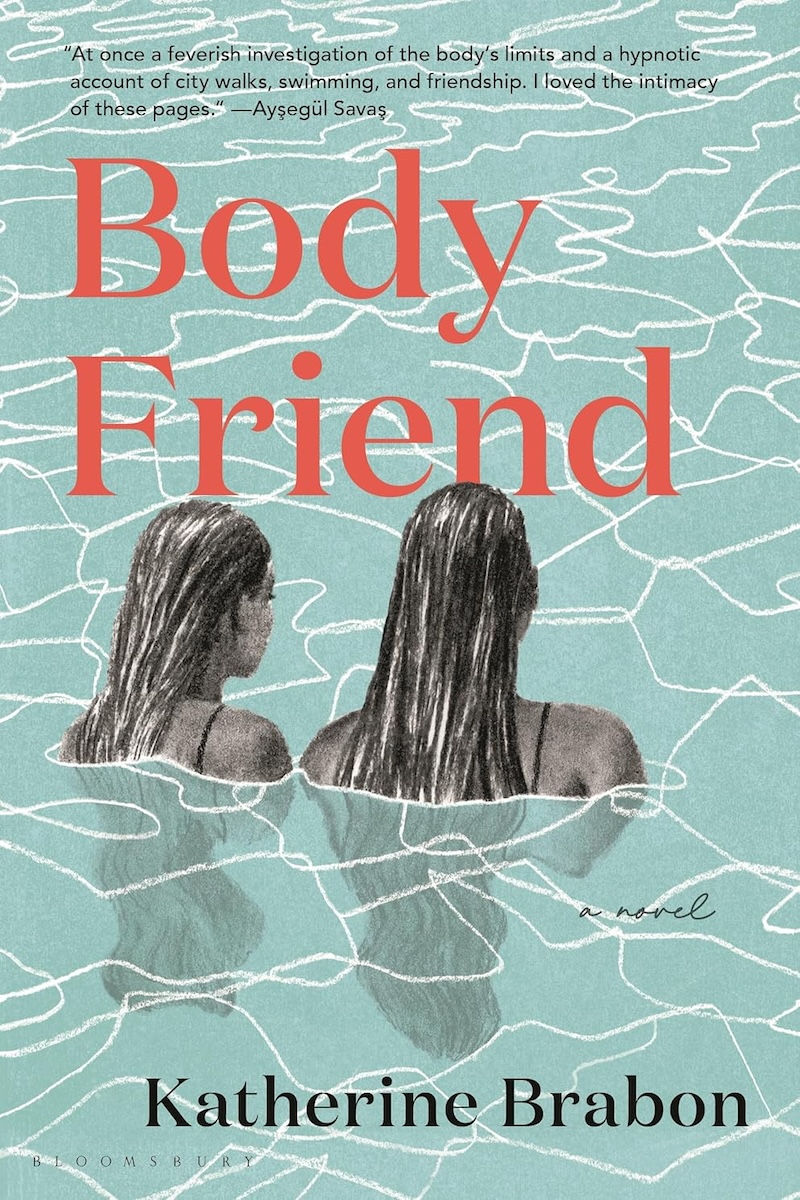

Book Review | ‘Body Friend: A Novel’ by Katherine Brabon

A Potent Story of Chronic Illness

In Katherine Brabon’s third novel, Body Friend, the narrator is never named. She’s a woman who knows herself best when she’s in the greatest physical pain, a result of an illness which also goes unnamed. The chronic pain she suffers defines her.

She’s a graduate student, a teacher, a writer, with a kind and patient boyfriend named Tomasz. They live in a shared house with a balcony. As the novel begins, she’s recovering from surgery, aware of a new artificial joint, anxious about the scar. Muscles that had atrophied are suddenly being used again, stretched and pulled as she relearns to walk with an even stride. She’s in convalescence which to her is a state of being that suggests a path leading to somewhere beyond.

She joins a hydrotherapy class with others in various stages of ill-health or recovery. Two Italian women in their seventies who struggle to reach and put on their socks, a young woman with a body bearing several surgical scars. She notices that some people move better in water than others, including a woman about her same age, same build, same long and blonde-auburn hair. This is Frida. At first the narrator observes the way Frida moves, and it’s like watching a distant mirror, the likeness uncanny.

“With this mirror woman I didn’t feel her pain but rather I knew it, because it was also mine. Towards her pain I felt the same banal familiarity.”

The women bond in the pool, and later swim together in the open ocean and talk over coffee. They suffer from the same illness, display similar outward symptoms: swollen joints, stiff necks, rashes. To be a body in pain is to recognize the same in another. The narrator becomes obsessed with Frida, pulled into her orbit. There’s a fierceness about Frida: she’s not inclined to give in to her pain, to use it as an excuse or allow it to stop her from swimming or walking.

Frida prods them both toward recovery and health.

And then the narrator meets another woman who is also about her age, Sylvia, whose hands are always hidden inside gloves, who wears baggy clothes. “I feel like I recognize you,” Sylvia says, “from sometime so long ago.”

Though no less obsessive, this relationship is of a different character. Where Frida concedes nothing to illness, Sylvia constantly advises the narrator to rest, sit, sleep, do nothing. “You don’t need the ocean today. You can just sit today. It’s okay. We’re in pain.” The narrator opens up to Sylvia as they sit side by side on a bench in the park where they meet. Sylvia is so accepting and nurturing that the narrator forgives herself for not swimming, for not pushing past the pain and anxiety as Frida implores her to.

Frida occupies one pole, Sylvia the other, and the narrator moves between them, almost as if the women represent opposing sides of her own consciousness. The three are never together. If Frida and Sylvia met it would disrupt the soul-level alignment and intimacy the narrator feels. Aside from some cursory details we don’t learn much about Frida and Sylvia, their private lives, loves, or families. Brabon maintains a tight focus on the interplay between the women.

Bonded by physical pain, by water, by stillness, the narrator feels like she’s on a pendulum between two different selves, never certain which will prevail. The feeling is at times unsettling. “In a practical sense another’s physical pain can never be ours.” Pain is something woven tight to the self.

Near the end of the novel Frida’s condition takes a turn for the worse, and the pain can no longer be pushed through, ignored; she endures another surgery, with only the narrator for support. Meanwhile, Sylvia is also struggling, her joints swelling and angry. By now the narrator, if not exactly thriving, is well enough to return to work, and then move with Tomasz into a single-story house of their own in another area where she no longer encounters Frida or Sylvia. She leaves these women behind, almost as if they had existed only in her imagination.

In the end the narrator comes to this conclusion: “The person I was in front of each of them, I am not anymore. The pendulum I felt ticking back and forth between them no longer exists.”

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.