Solving the Housing-Versus-Hotels Riddle in Santa Barbara

City Looks into Adaptive Reuse, Restricting Hotel Development to Prioritize Housing

The hotel boom in Santa Barbara may be nearing its end, as the push to provide more housing is forcing city leaders to rethink the imbalance of developers choosing to build hotels instead of residential.

These city leaders held a meeting of the minds on Friday, July 26, with a special joining session between the City Council and city’s Planning Commission to gauge the group’s opinion on two potential solutions to the housing-versus-hotels issue: allowing underused downtown properties to be converted into housing through adaptive reuse and restricting new hotels by amending the city code to either eliminate new hotels or require developers to earn approval on a case-by-case basis.

“If we want more housing in the city, we need to do things that make residential development more attractive to those that produce it,” Planning Commissioner Lesley Wiscomb said during the discussion. “We need to develop policies that prioritize and incentivize residential development over hotel development.”

Converting Commercial

Converting underused buildings into housing may be the key to revitalizing the downtown, but according to developers attempting these types of projects, adaptive reuse comes with its own sets of challenges.

Last November, the Housing Authority of the City of Santa Barbara unveiled an innovative new project in the heart of downtown that served as a test model for adaptive reuse, with the conversion of a former retail space into 14 studio apartments at the former Sur La Table at 821 State Street. Done in collaboration with philanthropic developer Jason Yardi — who purchased the property and donated it to be used for affordable housing — the project was an immediate success, proving that housing could be built in downtown’s empty commercial spaces.

Architect Brian Cearnal, who designed the conversion project, spoke during the joining meeting to shed some light on the economic viability of adaptive reuse in the city. While he supports the idea of encouraging more commercial properties to be converted into residential, he said that the reality is much more difficult — and expensive.

“Doing adaptive reuse is not easy,” Cearnal said. “It is not cheap, yet it is so needed as an element of our housing goals.”

Ben Romo, the consultant who helped organize the adaptive reuse project alongside Yardi, told the council and planning commissioners that, while they were on the right track, there were certain details in the proposed plan that would create issues in the property conversions.

If the city really intends to bring life back into the downtown area through housing, he said, the tangle of red tape needs to be cut to help potential developers.

In the downtown area, Romo said, the city could consider lifting the inclusionary requirement that all new projects must have 10 percent of units set aside as affordable housing. In the central district, where “properties have the highest land values and construction costs are through the roof,” he said, requiring affordable units would tank many of the potential developments from the start — unless, like the State Street conversion, they are done in collaboration with a nonprofit or with donated property.

“We know no other owner or developer that would take the risk and invest the capital necessary to do a project like this with such a low return,” Romo said. “It’s super complex to do development, and there’s a huge risk.”

The city currently allows a “change-in-use,” but the proposed changes would allow for developers proposing an adaptive reuse project to receive more concessions, removing the requirements on parking and open space and allowing for “unlimited density,” according to City Planner Dana Falk.

Councilmembers and planning commissioners were supportive of the plan for adaptive reuse, though several boardmembers voiced concerns over the slow-moving review process and inclusionary requirement in the downtown area. As an alternative, the group asked that city staff look into “in-lieu fees,” which would allow developers to pay a sum of money to the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund instead of building the affordable units themselves.

‘More Housing, Not Hotels’

The other side of the issue is the prevalence of hotels in the city, and the zoning conflict in many areas that allow both housing and hotels. Currently, zoning codes allow developers to propose new hotel projects “by right” in certain areas, with no additional levels of approval necessary.

In many cases, sites that would be prime locations for housing development in the downtown area are in zones that also allow for hotels. “Development for housing on these sites is directly competing with hotel use,” Falk said.

To address this, the city is proposing a change in the zoning code that would either eliminate the hotel use altogether or require developers to earn a conditional-use permit from the city review boards. City staff gave several options for the areas that currently allow hotels, and asked for input on each area.

During public comment, President of Santa Barbara Property Group Trey Pinner raised concerns with the hotel restrictions, suggesting that the city should consider tackling the problem by making housing a more financially viable option to housing developers. If a hotel is more lucrative, he said, then developers should have the right to choose to build what they want.

But Councilmember Oscar Gutierrez, who has recently been on the campaign trail knocking on doors, responded by relaying what he had seen and heard from the people in the community.

“Other than some of the people in the room right now,” Gutierrez said, “I’ve not heard anybody in the community say that they want more hotel rooms. That’s even from hotel owners and employees of hotels that I’ve spoken to personally.”

Hotels in the city usually hover around 70 percent occupancy, leaving plenty of empty rooms on any given day, while the hotels struggle to maintain local staff. In some cases, Gutierrez said, hotel owners have resorted to allowing their employees to stay in vacant rooms because they can’t find housing in town.

“It just doesn’t make sense,” he said. “We need more housing, not hotels.”

Halting New Hotels?

Much of the discussion surrounded whether the city should allow for conditional use or take the more aggressive approach of eliminating hotel use altogether (except in the coastal zone). Commissioner Devon Wardlow, who has been the most vocal in opposition to hotels, said it would be better for developers to get a clear message from the city that no new hotels would be considered rather than allowing them a pathway to approval on a case-by-case basis.

“Again, this is not saying we’re not going to have hotels,” Wardlow said. “This entire report details the significant number of hotels we have today. They will continue to exist, and in the coastal zone, we will continue to get more hotels as well.”

Councilmember Meagan Harmon says her priority is having no more new hotels, though she mentioned that there might be legal concerns over eliminating the use altogether. Allowing a conditional use, she said, would be a “perfect balance to getting us what we want” while allowing for flexibility in the future.

In a series of straw poll votes, the majority of the group supported allowing adaptive reuse of existing hotels, in the Central Business District and in buildings with historic resources, and everywhere in the city limits if developers promise to build 100 percent low-income-affordable units. Some boardmembers wanted city staff to look into other concessions for developers who were willing to offer a portion of affordable, at least 50 percent moderate-income units.

The group also supported eliminating hotel use in areas zoned for multi-family residential, the upper State neighborhood, and the manufacturing commercial zones near Haley and Gutierrez streets. For the Milpas neighborhood and areas covered in the city’s priority housing overlay, the group was split between eliminating hotel use or requiring conditional-use permits.

This is far from the finish line, as city staff will now take comments from the meeting and work toward crafting a draft ordinance before at least four more public hearings at the Planning Commission, Ordinance Committee, City Council for introduction, and then back again for council adoption of the proposed changes. As part of the city’s housing element plan, the goal is for the programs to be implemented by December 2025.

Premier Events

Sun, Jan 26

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

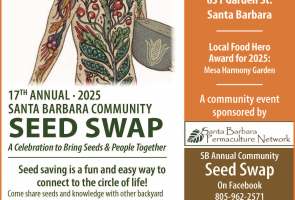

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sun, Jan 26

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Tue, Jan 28

5:00 PM

Zoom

Fire Safety Community Zoom Meeting

Thu, Jan 30

8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31

9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08

12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Adrien Brody and Guy Pierce

Sun, Jan 26 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sun, Jan 26 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Tue, Jan 28 5:00 PM

Zoom

Fire Safety Community Zoom Meeting

Thu, Jan 30 8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31 9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08 12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.