It has been some time since I finished a novel and immediately felt compelled to turn back to the first page and start over. The Overstory by Richard Powers moved me this way. I knew Powers by name and reputation, and from reading a review of Bewilderment by my colleague David Starkey, but had never read him. During a visit to the Strand Bookstore (a reader’s nirvana) in New York City, my son handed me The Overstory, promising it would captivate me.

My son was right. I read most of the novel on a flight from Newark to Phoenix. It’s a magnificent tale, and I don’t exaggerate when I say I almost couldn’t bear to put it down. Masterfully conceived and executed, full of intelligence and wisdom, essential questions about humankind’s often destructive relationship with the planet and, in particular, trees. Heavy stuff to be sure, but I didn’t find Powers to be pedantic or heavy-handed.

When I was 6 years old, I stood alongside other kids from my neighborhood and watched men and bulldozers demolish a walnut orchard that sat at the end of our street. Before the arrival of heavy machinery, the orchard was our playground, a magical place of dappled sunlight, shadow, a thick carpet of leaves, a home for birds, ideal for games of concealment, mock battles. The orchard was private property, of course, and we weren’t supposed to be there, and were often chased off by an old farmer, who probably wasn’t as old as he appeared to my 6-year-old self.

Once the orchard was cleared and graded, different men came and drove thin stakes decorated with pink, white, and red flags into the ground. My dad explained that these were survey markers for the construction that was coming, a Ford dealership, an office building, homes. Although nowhere near as magical, the cleared land was a fantastic place to build underground forts and wage battles with dirt clods, so the neighborhood kids had a vested interest in delaying the day of reckoning. We repeatedly yanked and scattered as many survey stakes as we could, sure this would gum up the works.

It didn’t. We failed to halt “progress” as surely as Maidenhair and Watchman do in The Overstory.

The violence I witnessed as those walnut trees toppled in an explosion of roots and dirt is indelible in my mind. All these years later, I can still see the massive piles of trunks and branches and twisted roots. As I read deeper into the novel I also recalled the shock I experienced upon seeing clear-cuts in “managed” forests in Oregon and Washington, entire hillsides dotted with stumps and slag.

Trees link the lives of the characters, from the massive chestnut that has been part of Nicholas Hoel’s family for generations, to Patricia Westerford, who as a graduate student in the midwest recognized that something was wrong with the way the men in charge of American forestry thought about trees, to Neelay, the precocious son of immigrants who becomes paralyzed for life after falling from a tree. The characters are like a root system, crossing over and under one another, seeking succor and connection, mutual aid.

As phrased by the writer Rick Moody, “Fiction is the lie that tells the truth.” This neatly sums up how I feel about The Overstory. Through his characters and their circumstances, Powers poses questions that the world barely addresses let alone answers, such as: “How is extraction ever going to stop? It can’t even slow down. The only thing we know how to do is grow. Grow harder; grow faster. More than last year. Growth, all the way up the cliff and over. No other possibility.” In a financialized global economy, growth is the Holy Grail, even if it produces awful consequences for millions of people and the health of the planet.

The parts of the novel in which Patricia Westerford featured brought to mind ideas I encountered in nonfiction books such as Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer and A Forest Journey by John Perlin, both of which I reviewed for this website. These books center the profound relationship between people and trees, and the consequences of ignoring that relationship. In the case of Braiding Sweetgrass, consequences spring from rejecting the indigenous knowledge gathered through close observation over millennia. Both books celebrate trees as givers of life, of food, of shelter, of shade, of respiration, of medicine — as vital parts of a complex system on which life relies.

As Adam Appich and his co-conspirators prepare to execute the act of eco-terrorism that carries such bitter consequences for them all, he experiences a moment of doubt. Is he mad to deny the bedrock of human existence, which is, as he perceives it, private property and mastery of Nature. What else counts? “Earth will be monetized until all trees grow in straight lines, three people own all seven continents, and every large organism is bred to be slaughtered.”

Adam’s pessimism is well-founded. He and his compatriots are tilting at windmills and like most who choose this path, experience loss far more often than the thrill of winning. The men and machines and money and force of law behind them are insatiable and sweep aside all obstacles. That’s one way to look at it.

Another way, which depends on a more capacious concept of time, is that a seed can lie dormant for thousands of years, patiently waiting for the right conditions to begin life anew.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

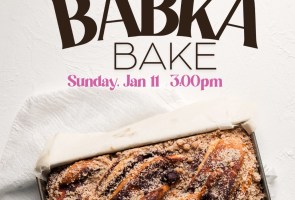

Premier Events

Sun, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 02

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with King Bee!

Fri, Jan 02

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ DJ Claire Z 1.2.26

Fri, Jan 02

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Cosmic Dawn: When Galaxies Were Young

Sat, Jan 03

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Nic & Joe go Roy

Sat, Jan 03

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04

7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Mon, Jan 05

6:00 PM

Goleta

Paws and Their Pals Pack Walk

Mon, Jan 05

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancient Agroecology: Maya Village of Joya de Cerén

Tue, Jan 06

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Amazonia Untamed: Birds & Biodiversity

Wed, Jan 07

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

Sun, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 02 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with King Bee!

Fri, Jan 02 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ DJ Claire Z 1.2.26

Fri, Jan 02 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Cosmic Dawn: When Galaxies Were Young

Sat, Jan 03 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Nic & Joe go Roy

Sat, Jan 03 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04 7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Mon, Jan 05 6:00 PM

Goleta

Paws and Their Pals Pack Walk

Mon, Jan 05 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancient Agroecology: Maya Village of Joya de Cerén

Tue, Jan 06 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Amazonia Untamed: Birds & Biodiversity

Wed, Jan 07 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara