Homeless in Santa Barbara: From Hobo Jungle to Living in Cars

Trying to Solve the Same Old Problem With the Weird and the Wonderful

SAME OLD SONG: Things don’t ever really change; they just get more the way they are.

I don’t know if this qualifies as a mangled variant of Isaac Newton’s First Law of Nature — that bodies in motion stay in motion, and that bodies at rest stay that way, too — or a new Fourth Law Newton never got around to figuring out.

Calling this conundrum to mind is the fundraising gala hosted by New Beginnings taking place June 20 — tickets, I am told, are still available — to celebrate the 20-year anniversary of their wildly but quietly successful Safe Parking Program. At last count, this program sets aside 178 managed and curated parking spaces in 27 nighttime parking lots scattered throughout the county for people who find themselves forced by economic realities to live in their cars.

Like the Egg McMuffin, ranch dressing, and the tri-tip barbecue, Safe Parking originated right here in Santa Barbara — in the downtown parking lot behind the County of Santa Barbara’s Administrative Building. Born out of necessity and in the spirit of improvisational creativity and chaos, it proved so successful that it’s spawned a massive number of spin-offs throughout the country.

Western civilization did not crumble, as many predicted at the time. Of all Santa Barbara’s big-time events now marking major anniversaries this year — Fiesta and Roosevelt Elementary School turn a blushing 100, and Solstice hits 50 this week — this may be the one most in urgent need of “celebration.”

That’s because right now, roughly 600 county residents live in their cars. That population has increased by about 20 percent in each of the past three years. The real numbers, no doubt, are much higher. These are people who desperately don’t want to be seen and have learned how to blend in. More than 80 percent of Safe Parking clients are 55 or older. A handful are in their nineties. Life didn’t work out quite as planned.

It’s not exactly rocket science. Rents have exploded. Incomes are fixed. People live longer. The number of shelter beds has plummeted. Maybe a few bad decisions got made along the way.

At the same time, long-term, single-room-occupancy hotels — until recently an abundant ecosystem of genuinely low-income housing — have gone the way of the white rhino.

And who wants to live in a shelter?

The keynote speaker at this Thursday’s event happens to be a badass sociologist from Connecticut named Michele Wakin, who’s done more actual dirt-under-the-fingernails research on homelessness in Santa Barbara than all but one or two people alive on the planet.

What Wakin will talk about exactly, I don’t know. She was too busy putting the finishing touches on her new book. Her most recent book, a sociologically minded history of Santa Barbara’s sprawling hobo jungle (located for decades where the zoo now stands) proves yet again that fact trumps fiction every time when it comes to all things being weird and wonderful.

Depending on what source you want to believe, Lillian Child first opened a portion of her 17-acre waterfront estate to a large colony of hobos — in 1915, 1919, or 1935. Depending on the year, there were anywhere from 32 to 60 older men living there in a semi-permanent settlement of tarpaper shacks they constructed on the site. They lived there for decades.

The sanitation, to put it delicately, was crude — outdoor privies. Jungleville residents elected their own mayors and maintained their own sense of order. Former Judge Jack Rickard told me that, back when he was the City of Santa Barbara’s mayor in the mid-’50s, he would meet once a year with the mayor of Jungleville and exchange diplomatic and ceremonial pleasantries.

In other words, it was a thing. Weird. Eccentric. Resented in some quarters. But accepted.

What is actually known about Lillian Child is not nearly enough — often the case when wealthy, headstrong women are involved. She reportedly opened her grounds to what the local press then described as “vags” or “Weary Willies,” after witnessing two of Santa Barbara’s finest attempting to arrest a couple of hoboes for crimes they had not yet committed but that the officers were certain they soon would.

Whatever “it” is, Child apparently had enough of “it” to have married three millionaires in her lifetime, divorcing one and burying two. That — and the 17 acres she inherited — enabled her to tell the local cops to pound sand. She called the shots as she saw fit.

What’s most striking in the historical record is the stunning lack of curiosity about Child and her motivation. But maybe she did not take kindly to questions. When asked on one occasion if “kindness” was a factor, Child bristled, “Kind? There is nothing kind about it. I never think of it as kind.”

The residents of Child’s “Hobo Ritz” or “Hobo Hostel” would probably not qualify as “our unsheltered neighbors” or “the homeless” by today’s standards. “Vagrants” have long been regarded as the bane of existence by the city’s mothers and fathers. Press clippings from 1903 and 1906 loudly bemoaned the tsunami of road tramps then reportedly inundating Santa Barbara and how it was prohibitively expensive to lock them up in county jail. New cops needed to be hired! That song sound familiar?

News accounts wrote admiringly of “rockpile” therapy, in which vagrants were forced to smash large rocks into much smaller ones. This would discourage unwanted visitors from ever coming, they pointed out, while providing cheap but necessary labor for road repairs.

All, in other words, was not warm and fuzzy.

By 1955, most of the residents — about 32 — had grown long of tooth and creaky of bone. In response, another local millionaire who’d made his fortune manufacturing a mentholatum-based foot powder for cooling the feet — Alex Hyde — took an interest in the plight of the Jungleville residents.

By then, Child had been dead for four years, her property bequeathed to the Santa Barbara Foundation and then fobbed off to the City Parks Department. Hyde had heard — from the Jungleville mayor — that a cinderblock building with a rec center, showers, toilets, and washing machines — would be greatly appreciated by the older residents.

Hyde — a share-the-wealth capitalist and devout Christian — enlisted the assistance of a young city cop named Noah “Stormy” Cloud to the cause. Cloud likewise enlisted two African American teen clubs — the Cavaliers and Cavalettes — and together they took their case to City Hall to secure the necessary permits.

Ultimately, the council voted in favor of the plan, but only after Mayor Rickard stressed the residents’ days were numbered. Already, the Jay Cees (junior chamber of commerce members) had sized up the property as the possible site for a city zoo. One councilmember — Donald Dockendorf — expressed concern. “If you upgrade it, you are going to bring a lot of guys in there,” he objected. In response, Officer Cloud asked, “Where are you going to send them?”

“Wherever they came from,” Dockendorf answered.

“They are citizens of Santa Barbara,” Cloud replied.

And we’ve been having the exact same argument — in the exact same terms — for the past 68 years.

In 1959, the Child family’s pink Vegamar estate — having been occupied and partied into the ground by a then-fledgling UCSB fraternity — was torched by the city fire department. Officer Stormy Cloud had been given a young-man-of-the-year award by the Jay Cees and left Santa Barbara in 1956 to take a job with the Orange County Probation Department. In 1962, Hyde — the mysterious foot-powder millionaire — was killed in a car crash and his wife was badly injured. In 1963, Santa Barbara’s brand-new zoo opened to the public. And for the last three Jungleville residents, housing was found.

I have no idea what Michele Wakin plans to talk about this Thursday. But I can’t wait to hear. In the meantime, we’re still singing the same old song, only louder

Premier Events

Wed, Jan 08

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Country Line Dancing at Soul Bites

Wed, Jan 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Broadway In Santa Barbara Presents “Mean Girls”

Thu, Jan 09

12:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Thursday Lunchtime Meditation Class

Thu, Jan 09

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow: A Vision Board Party

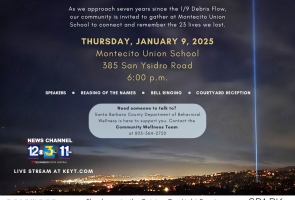

Thu, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

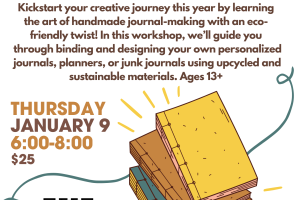

Thu, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

DIY Journal Workshop

Sat, Jan 11

9:00 AM

Goleta

Coffee & Community at Armitos Park/ Café y comunidad en Armitos Park

Sat, Jan 11

11:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Crafternoon: Sustainable Stagecraft

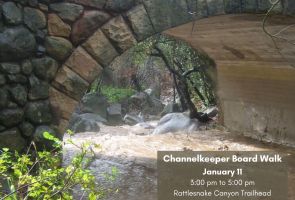

Sat, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Rattlesnake Canyon Walk

Sat, Jan 11

3:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

Santa Barbara Music Club Free Concert Jan 11, 2025

Wed, Jan 08 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Country Line Dancing at Soul Bites

Wed, Jan 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Broadway In Santa Barbara Presents “Mean Girls”

Thu, Jan 09 12:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Thursday Lunchtime Meditation Class

Thu, Jan 09 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow: A Vision Board Party

Thu, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Thu, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

DIY Journal Workshop

Sat, Jan 11 9:00 AM

Goleta

Coffee & Community at Armitos Park/ Café y comunidad en Armitos Park

Sat, Jan 11 11:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Crafternoon: Sustainable Stagecraft

Sat, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Rattlesnake Canyon Walk

Sat, Jan 11 3:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

You must be logged in to post a comment.