The formidable Ojai Music Festival has returned to the Ojai Music Festival (OMF) business at hand. Birds, unpaid and uncharted freelancers, chirp along in the idyllic venue of the Libby Bowl, along with the extra-musical sounds of welcome church bells and unwelcome car alarms and motorcycles. Festival-goers lounge into a weekend in a dreamy hamlet, catching concerts at 8 a.m. and throughout the day and evening. All is — and was — well.

But beneath the peaceful escapist element of the OMF, there are high stakes for this revered festival’s legacy and in consideration of its role in the evolution of music of the now, informed by music of the then.

Last year, this internationally important festival — mostly about classical music, and, within that umbrella, mostly about contemporary or recent-ish music — took a fascinating side trip courtesy of the immensely gifted and versatile Rhiannon Giddens as music director. She folded her musical voice and vision, from Americana (and African-Americana) to her new status as Pulitzer Prize–winning opera composer (for Omar) and shook up the old Ojai guard, while luring in new audience factions.

Last weekend, the OMF felt more aligned with the agenda laid out over its now 78-year history, with the eminent pianist Mitsuko Uchida in the director’s seat, and a solid program of music spanning a Baroque-to-contemporary perspective. Uchida, whose musical reach includes working with Vermont’s Marlboro Festival, brought along the bold Mahler Chamber Orchestra as resident ensemble, along with the sharp Brentano Quartet and such bedazzling young artists as violinist Alexi Kenney, lateral-thinking cellist Jay Campbell (the “C” of the JACK Quartet) and accordionist Ljubinka Kulisic.

As for the detailing in the program’s texture and range, the composer focus ranged from the fundamental loam of Bach, Haydn and Mozart to composers she has worked with—the late Finnish Kaija Saariaho, the Russian Sophia Gubaidulina, the German Helmut Lachenmann, Arnold Schoenberg and a powerful “newcomer,” German Jörg Widmann, whose “Chorale Quartet” on closing night was this listener’s pick for best of fest, in terms of a new discovery.

For her part, Uchida dove deep into her famed poetic prowess as a Mozartean, performing three Mozart Concertos in primetime evening concerts. It could be argued that this may have been one or two too many major Mozart works, for a festival which has built its reputation and global standing by championing music of our time (and times). But the argument leaned in Uchida’s favor, given the sublime experience of hearing her grace these scores with her uncommon depth of understanding — while leading the MCO between her keyboard flights.

Uchida was the ideal choice as music director at this moment, contrasting the Giddens year with a more Ojai-centric grounding. She first appeared here in 1996, with Pierre Boulez at the helm, and then returned as co-director with David Zinman, and then later as performer.

In programming cahoots with artistic director Ara Guzelimian, Uchida managed to tap many important and lesser-heard musical touchpoints over the weekend, including paying respects to Saariaho, who died just more than a year ago. Her Lichtbogen, conducted here by her daughter Aliisa Neige Barriere, has a shimmering, evanescent atmosphere, mixing acoustic and electronic elements with abiding sensitivity (this 1986 piece was her first in collaboration with the Boulez-run IRCAM lab in Paris).

Schoenberg had a special slot in the festival programming, given his status as a game-changing 12-tone architect revolutionary. But the emphasis here was on key works — the String Quartet No. 2 (with soprano Lucy Fitz Gibbon joining the Brentano) and his Chamber Symphony — which led up to his internal metamorphosis from late romantic to systematic atonality guru. In these works, we hear a composer rattling the cage, still trying to burst free into his own new language.

To my ears, the weekend’s most powerful Schoenberg came in the compact form of his solo piano work “Six Little Pieces,” the first piece we heard from Uchida on Thursday night’s opening concert, and eight minutes of modernist bliss. The finest example of emotionally expressive serialism this weekend came from Schoenberg student Anton Webern’s classic “Five Movements for Strings.” Row music rarely sounded so sweet. Well, bittersweet, with an objective air.

In more general local terms, the festival furthered the recent question: Is it the dawning of the age of accordions in the 805? The presence of superlative Bosnian Kulisic at this festival marks the third notable classical accordion siding this season. She had appeared in these parts, after last fall’s appearance by the Chinese Hanzhi Wang at the Lobero Theatre and last month’s premiere of Clarice Assad’s new work for accordionist Julien Labro, at Hahn Hall.

In Ojai, we first got acquainted with Kulisic at a striking Friday 8 a.m. concert in Zipper Hall (on the campus of the Besant Hill School in Upper Ojai), as the partner of cellist Campbell on Gubaidulina’s In Croce — repeated at the Libbey Bowl, the only work played twice here. She later impressed in both contemplative and maverick party modes, with a delectable early morning program of John Cage works at 8 a.m. in the Chaparral Auditorium and, at the Libbey Bowl, navigated the tricky road map of John Zorn’s wildly impish postmodern mash-up Road Runner.

As has happened in recent years, some of the more intriguing and off-radar music of the Ojai weekend takes place in the early morning slot, says one who is decidedly not a morning person but will rise to a good musical occasion. Friday’s program featured Campbell’s experimental eloquence on Saariaho’s deconstructive Dreaming Chaconne and Lachenmann’s delicate percussive extended techniques on Toccatina. Lachenmann also supplied the tour de force percussion piece Interieur I, which festival newcomer Sae Hashimoto performed with a wizardly choreographic — and highly musical — grace.

On Saturday morning, Campbell took charge of transforming the inviting old-school Chaparral Auditorium into a meditation zone with intellectual overtones (a bounty of overtones, actually), in the form of American-in-Berlin composer Catherine Lamb’s solo cello piece “The Additive Arrow.” Via elaborate computer sound-chasing programming and additive processes, the half hour work built up a hypnotic swirl of sounds and overtones, with a palette of 32 notes to the octave. The sum effect was mind-bending, and mind-mending. It is also one of those pieces you have to experience live in a room to fully appreciate.

Aptly enough, the main Sunday morning Libbey Bowl concert came equipped with religious resonances of varying types and idioms. Kenney played the “church music” of baroque composer Heinrich Biber’s Passacaglia for solo violin, circa 1676, followed by the gentle percussion poetry of Saariaho’s Six Japanese Gardens, vaguely tinged by Buddhist qualities and radiantly delivered by Hashimoto. The centerpieces came next, with a section from Haydn’s The Seven Last Words of Christ (played by the Brentano, with its usual aplomb), and Russian Orthodox-linked Gubaidulina’s In Croce (“On the Cross”), closing with ascending cello motives versus descending accordion chords, landing in a redemptive resolution.

Special “off campus” afternoon concerts featured the refined and adventurous young Kenney (who, incidentally, will appear in Santa Barbara with his group Owls next year), in the Greenberg Center of Ojai Valley School. His elaborate “Shifting Ground” program, with visuals by Xuan — sometimes symbiotic with the music, sometimes not — blends the grounding force of Bach with more modern material, including Saariaho, his Owls comrade Paul Wianco (also in the Kronos Quartet) and the angular and taut, soloist-with-electronics maze of Mario Davidovsky’s Synchronisms No. 9, from 1988.

Sunday afternoon found Kenney impressing in a different, more internally programmatic direction, joining soprano Fitz Gibbons on the great Hungarian composer Gyorgy Kurtag’s engaging, angst-filled and humor-sprinkled Kafka Fragments.

As for other high points of OMF 78, we couldn’t help but love the rumbling minimalist charm of John Adams’s Shaker Loops, a still-vital seminal work from the composer who directed the 75th anniversary festival and whose music resonates deeply in this place, on this stage.

And then there was the thrill of Widmann’s Sunday evening triumph, with MCO’s masterful reading of his Chorale Quartet. In a sense, here we had the ultimate expression of the weekend’s over-arching theme, connecting early music — which arrives in ghostly patches in the score — alongside thoroughly modern approaches to experimentation with instrumental color and ensemble writing. We hear a similar searching synthesis effect in Widmann’s 2017 epic Arche, a two-hour piece honoring the opening of Hamburg’s great new orchestra hall the Elbphilharmonie (take a listen here).

In this music, new meets and wrestles with old, coming to agreeable understandings and paving the way for future discussion. So went the OMF, circa 2024. Next up in the discussion, 2025 music director Claire Chase, an iconoclast with a sense of play and depth. We’re all ears.

Premier Events

Sun, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Sat, Jan 03

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Nic & Joe go Roy

Sat, Jan 03

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04

7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Mon, Jan 05

6:00 PM

Goleta

Paws and Their Pals Pack Walk

Mon, Jan 05

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancient Agroecology: Maya Village of Joya de Cerén

Tue, Jan 06

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Amazonia Untamed: Birds & Biodiversity

Wed, Jan 07

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

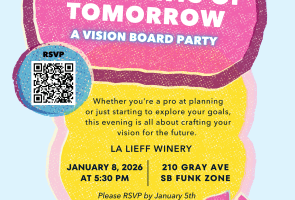

Thu, Jan 08

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

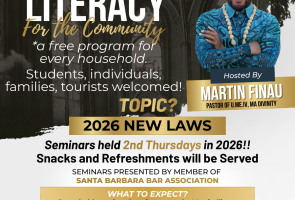

Thu, Jan 08

6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Music Academy: Lark, Roman & Meyer Trio

Sun, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Sat, Jan 03 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Nic & Joe go Roy

Sat, Jan 03 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04 7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Mon, Jan 05 6:00 PM

Goleta

Paws and Their Pals Pack Walk

Mon, Jan 05 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancient Agroecology: Maya Village of Joya de Cerén

Tue, Jan 06 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Amazonia Untamed: Birds & Biodiversity

Wed, Jan 07 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

Thu, Jan 08 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

Thu, Jan 08 6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.