Santa Barbara County Approves Rezones for South Coast After Marathon Planning Effort

Board of Supervisors Choose 28 Sites That Could Bring More than 5,000 Units of Housing

It’s a new era in housing development in the state of California, and ever since Governor Gavin Newsom vowed to build 2.5 million units of housing by 2030, every region has felt the pressure. Here in Santa Barbara County, planning staff had to account for at least 5,664 in the unincorporated areas of the county over the next eight years, with at least 4,142 along the South Coast from Goleta to Carpinteria.

This required the county Board of Supervisors, Planning Commission, and planning staff to scour hundreds of parcels to assess which sites would be rezoned in the name of housing. Supervisor Joan Hartmann called this a “staggering effort” by the county planning staff, which had to navigate “unmovable state regulations, a “skeptical and frustrated” Board of Supervisors, and the “hot fires of intense public opinion” over the rezone process.

On May 3, the board officially approved its list of 28 sites on the South Coast that could bring more than 5,000 units of housing. On the same day, the board approved nine sites in North County for another 3,500 units.

Supervisor Hartmann acknowledged the gravity of the decision during the nearly eight-hour hearing, saying she has watched her home state “utterly transformed” over the past few decades due to the impacts of the housing crisis.

Hartmann said she has seen “families pulled apart” because adult children can’t afford to live in the same communities where they grew up, tenants displaced due to “renovictions,” and “way too many families with children renting a single room in a home with other families because they just can’t afford more.”

“The lack of housing is hollowing our community,” Hartmann said. “So today, it’s with a great deal of personal anguish that I find myself considering approval of the most controversial set of housing rezones the county has ever adopted.”

Supervisor Laura Capps, whose 2nd District in the Eastern Goleta Valley was hit with the biggest chunk of housing — nearly 3,000 units of housing proposed within a three-and-a-half-mile radius — said that it was “a huge step, but just the beginning step” to addressing the needs of the county’s low-income workforce.

“It would be a challenge to raise an issue that we deal with in the county that isn’t impacted by the fact that housing is so expensive and out of reach for most people,” Capps said.

Supervisor Capps joined the board as the rezone process was already underway in late 2022. But ever since joining, she has been vocal about the need to encourage higher levels of affordability in all the projects being considered for rezones, while also pushing for the county to do its part by offering some of its own land to be developed into housing.

After the county hosted a developer workshop in March, which became a beauty contest of potential housing developments, almost every project increased its number of affordable units, with some pushing over 50 percent below market rate housing. The county offered up 320 units, with 278 dedicated for low- and moderate-income households.

Still, the county’s approved rezones (a full list can be viewed here) include a substantial amount of above-market-rate housing, something that the planning staff and board explained was needed in order to meet the state’s low- and moderate-income housing goals.

“We don’t need to rezone any market-rate housing,” Capps said, “but without the market rate, we wouldn’t meet the low-income goals.”

The board chose 16 of 18 potential rezone sites in addition to nine county-owned sites and two sites that had pending projects already underway. With all these sites, the county would meet the state’s affordable housing goals plus a 15 percent buffer. But while the county is 360 units above the threshold for low-income units and 250 above the mark for moderate-income, it expects to come in with more than 2,500 units of market-rate housing above what the state requires.

There were no major surprises in the board’s decision, though more than 90 people gave public comment during the hearing, many of whom represented neighbors raising concerns against potential projects near Goleta.

The Glen Annie project, which could bring 1,000 units to the golf course on Cathedral Oaks Road, was approved despite a wave of public backlash over traffic impacts in the busy intersection. It was praised for its high number of affordable units — 300 lower-income and 350 moderate-income — and the developer’s willingness to work with the county and donate 7.7 acres of the land that would be used for Santa Barbara Unified School District staff housing.

Supervisor Hartmann suggested that the county look to the state for support with traffic mitigation for Glen Annie. “The state is imposing these housing requirements; I think the state has to come up with more support for the infrastructure to help us manage the impacts of these projects,” she said.

The Orchard project, which proposed 1,177 units of mixed income housing, was denied a rezone after members of both the Planning Commission and the Board of Supervisors agreed that they could not move forward with every proposed rezone in the Goleta area. But the project could still move forward under Senate Bill 330, which would allow the development of the land under the “builder’s remedy.”

Premier Events

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Wed, Jan 22

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Talk: “Raising Liberated Black Youth”

Sun, Jan 26

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

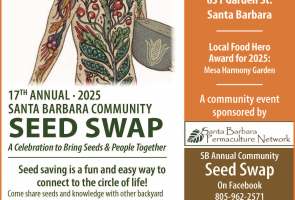

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Thu, Jan 30

8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31

9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08

12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Adrien Brody and Guy Pierce

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Wed, Jan 22 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Talk: “Raising Liberated Black Youth”

Sun, Jan 26 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Thu, Jan 30 8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31 9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08 12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara