Attention, technophobes and technophiles alike: SBMA wants to borrow your eyes and imaginations. Artists gathered in the current Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA) exhibition — Made by Hand/Born Digital — have, in various ways, drawn on computer systems or the warily received world of AI directly, in the preliminary stages and sometimes finished-product phase of their work.

Far from casting aspersions or nurturing fear-mongering regarding the techno-present, this show gamely presents a friendlier, gentler vantage on the uses of the tech and AI specter/promise, art division. We could easily argue the timeless merits of artistic practices for art’s own sake, divorced from the info-overloaded world. But evidence for the defense makes an intriguing case for itself in the museum’s upstairs contemporary gallery, where the museum’s more envelope-pushing art is known to dwell.

Often, the digital aspect of the work in the show is deceptively enmeshed in the end result before us. Tech art is certainly not the first impression given by Yassi Mazandi’s sculpture “Nine,” a circle of spindly bony forms, suggesting spinal forms or vertebrae, or an orderly coral display. The repeating structure itself — which the artist refers to as “flowers” — was formed in the ancient manner, with clay and a potter’s wheel, but then 3D-printed using pulverized stone. The ambiguity of materials and reference points becomes part of the charm and conundrum of the art.

Large paintings leap out for our attention, with ulterior means and backstories enhancing full appreciation of what the art is about. Justin Mortimer’s “Dog” is disturbing in ways we may not immediately understand, with its fuzzy-formed image of a nude man on all fours in an alien-antiseptic room. It brings to mind the fever-dream quality of Francis Bacon’s gnarled figurative paintings.

Here, though, the process moves beyond timeless pigment-on-canvas painting tradition, in that the classic “sketch” stage was supplanted by working with collaged magazine cuttings and Photoshop wood-shopping, leading the artist to the final, strange, and strained final painting.

Similarly, technology in the formative creative stage lurks behind Ena Swansea’s fairly massive painting “area code, 2019.” She culled and reflected on thousands of digital photographs before coalescing the reality-twisting view before us on the wall — a retro phone booth (with her young son inside) in a forest scene appearing everything but natural. With its fragile, faux pixelated surface, the imagery nudges our bearings duly askew, fueled by data points that compute more as artistic fantasy than realism of the old-school sort.

Shifting in yet another, and highly personal, direction, Taha Heydari’s “Reterritorialization” contains a blurred and disoriented vision of the world we know, and its rules of order. In this case, the unsettled logic refers both to the inchoate world through AI’s eye-view and life in the artist’s past as an Iranian born just after the Islamic Revolution of the late 1970s. The title tells all in “Reterritorialization,” in sociopolitical and artificial intelligence terms.

Elsewhere in this purposefully divergent selection of contemporary artists, technology rears her/his/its head in different ways and to different degrees of artistic influence. Alex Heilbron’s “Dictation” and “Phonemic” represent almost a direct collaboration with digital forces of Photoshop and other design programs.

Pae White uses a computer-controlled laser cutter to burn off layers of ink and paper, in a machine-driven reductivist scheme.

Over in the tapestry art corner — which might seem antithetical to digital footprints — Sarah Rosalena’s “Exit Grid” blends vintage dyeing methods and a computer-controlled loom to create a colored fabric grid replete with glitches and raggedy elements in place. Shaker furniture makers included “mistakes,” so as not to offend God. Do tech-linked artists similarly celebrate the beauty of happy accidents, as proof of humanity?

The question is relevant in the case of Analia Saban’s “Pleated Ink (Music Synthesizer: Max MSP, 1996).” A rough and splotchy — and clearly handmade — ink-on-panel image is a fine and funky visualization of the readout of the well-established computer music software MSP/Max.

Saban’s piece faithfully lives up to the exhibition title Made by Hand/Born Digital, while artfully pondering the considerable gray zone between those two realms.

Made by Hand/Born Digital is on view at Santa Barbara Museum of Art through August 25. See sbma.net/exhibitions for additional information.

Premier Events

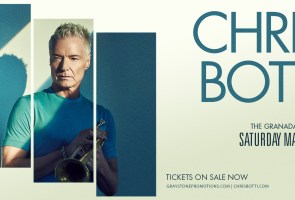

Sat, Mar 29 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Chris Botti in Concert

Sun, Apr 06 11:30 AM

Santa Barbara, CA

Gun Violence Prevention Forum with Asm. Gregg Hart

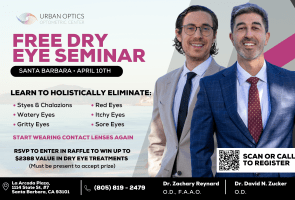

Thu, Apr 10 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Free Dry Eye Seminar w/ Dr. Zucker & Dr. Reynard

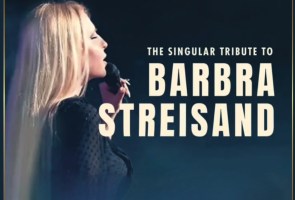

Fri, May 23 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Songbird: The Singular Tribute to Barbra Streisand

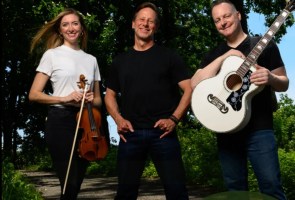

Thu, Mar 27 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Live Music Supporting Direct Relief

Fri, Mar 28 11:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Encore Screening: Cycling Without Age

Fri, Mar 28 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

The Happiness Habit (2 for 1)

Fri, Mar 28 7:00 PM

Ojai

Evening of Sacred Song & Mantra with Donna De Lory

Sat, Mar 29 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

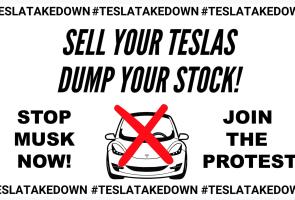

Global Tesla Takedown

Sat, Mar 29 10:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Children’s Resource Fair

Sat, Mar 29 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

National Vietnam War Veterans Day Celebration

Sat, Mar 29 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

3rd Annual Canned Food Drive and Community Event

Sat, Mar 29 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

MCASB Presents Los Tranquilos Mini Concert

Sat, Mar 29 5:30 PM

Santa Barbra

You must be logged in to post a comment.