On a bright spring day in 1967 at Santa Barbara’s seaside La Playa Stadium, a field of collegiate sprinters lined up for the start of the Easter Relays 100-yard dash. Standing tall among them was OJ Simpson, a new face in a USC Trojans track singlet, having recently transferred from City College of San Francisco.

At the crack of the starter’s pistol, Simpson exploded out of the blocks, sprinted powerfully down the dirt track and hit the tape in a winning time of 9.5 seconds. I was watching from the stands with a UCSB classmate from Los Angeles, and he had visions of grandeur for USC football, knowing that Simpson had been recruited to become Troy’s next tailback.

And so it happened. OJ took the college football world by storm, piling up the yardage with dazzling runs, including a 64-yard burst of broken-field artistry against UCLA. “OJ” or “Juice” became the most recognizable monikers in sports. Another play on his name was uttered by a Notre Dame coach: “Oh Jesus, there he goes again.”

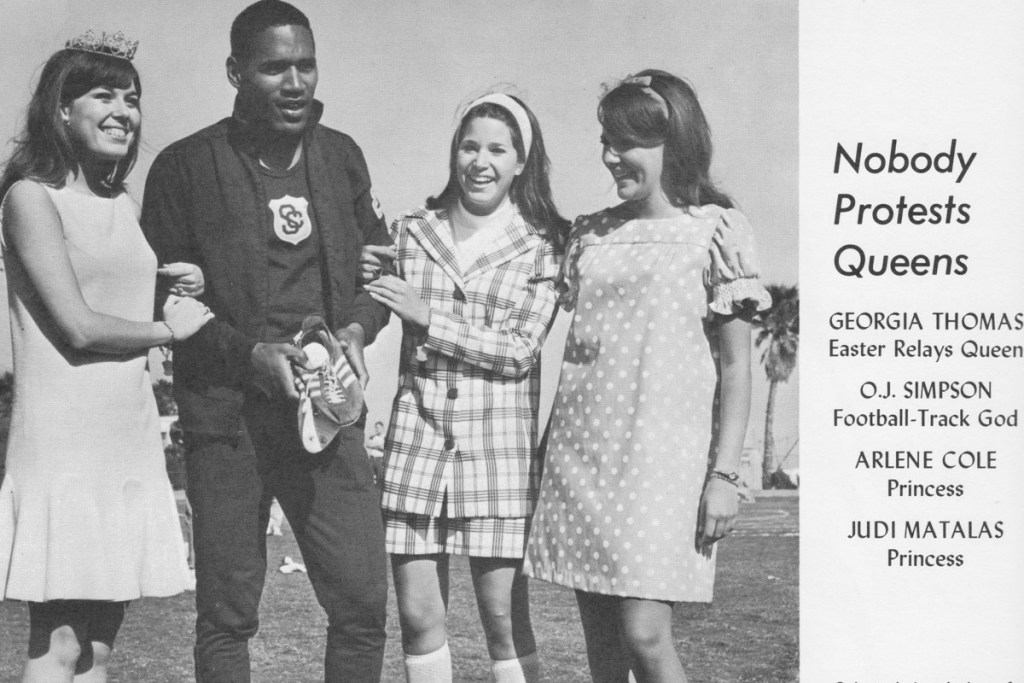

Santa Barbara gave OJ a hero’s reception at the next year’s Easter Relays, where he ran on USC’s sprint relay teams. He posed for a photo with three UCSB coeds, the queen and princesses of the Relays, and a caption in the UCSB yearbook described him as a “Football-Track God.” I was editor of that yearbook. In a year of anti-war protests and racial disharmony, OJ’s affable presence seemed to be an antidote.

In the fall of 1968, I was hired to a then-temporary position on the Santa Barbara News-Press sports staff. During the football season, I primarily covered the Dos Pueblos Chargers, the new high school team in town. When sports editor Phil Patton asked if anybody wanted to spend New Year’s Day covering the Rose Bowl Game, I eagerly volunteered. It was USC versus Ohio State, OJs last collegiate game.

Ohio State won, 27-16, overcoming an early 10-0 deficit fueled by OJ’s 80-yard touchdown in the first half. The game turned in the third quarter when OJ fumbled a pitchout. I stood a few feet from him in the dressing room after the game. He took the defeat with equanimity, blaming himself for mishandling the pitchout. “We made the most mistakes,” he said. “A good team capitalizes on mistakes. They’re certainly a very good team.” OJ then seemed no less a hero than I had imagined. Heroes take responsibility.

A few weeks later, I received a call from Sunset magazine, where I had interviewed for a job. They made an offer: Come and help cover the good life in the West. I declined. Partly because of the thrill of getting up-close and personal with the greatness of OJ Simpson, I decided to continue my budding career as a sportswriter.

I learned much about the profession from the book No Cheering in the Press Box, a compilation of reflections of noteworthy sports writers. The revered columnist Red Smith recalled that early in his career an editor told him to stop “Godding up those ball players.”

I never had another close encounter with OJ, but my godded-up image of him — shared by the media he was chummy with — remained mostly intact through his record-breaking NFL career and his years on the celebrity circuit, though he did at times seem too full of himself, as when he was filmed in a video, holding up his newborn baby Justin, and the first thing he said was, “Don’t I look good at 41?”

Then the news broke that OJs ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman were murdered on her doorstep the night of June 12, 1994. I could not believe OJ had anything to do with the crime. But then came credible accusations, the flight of the Bronco, and OJ’s arrest.

Revelations of domestic abuse, of a rage he concealed from the public — that was brushed off by authorities — made me realize that I did not truly know the man beyond his exploits on the track and the gridiron.

While OJ’s televised trial was going on, I visited Lowell Steward at his home in Oxnard. Steward had flown 143 missions in World War II with the Black pilots who were featured in a new HBO movie, The Tuskegee Airmen. He told me he was driven to prove himself in air combat after a painful rejection in the land of Jim Crow. Steward had been the leading scorer and rebounder on UCSB’s 1941 basketball team, but when the Gauchos were invited to play in a national tournament in segregated Kansas City, their Black star was banned from participating.

He endured other slights because of his color — in full uniform, he was refused service at an L.A. restaurant, he could not buy property in certain neighborhoods, he had to be wary of the police — and when our conversation turned to the Simpson trial, I gained an insight into the upcoming verdict.

Steward jumped on the revelation that Mark Fuhrman, a lead detective in the murder case, was a brazen racist. “Look at what Fuhrman could do, even though he was hired to protect the public,” he said. “The best thing to come out of this is that maybe people believe Blacks when they complain about the police. …The prisons are full of Blacks convicted on phony evidence.”

As for Simpson, Steward said, “He’s guilty as hell,” but he could see an L.A. jury deciding otherwise as retribution for past injustices.

“OJ will suffer if he did it and got away with it,” Steward added. “An explosive life will wear him out.”

I wrote several stories about Lowell Steward — the last when he and other Tuskegee Airmen received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2007 — and I unapologetically deigned him a hero. He died on December 17, 2014, at the age of 95.

OJ Simpson did go free, but he later had to serve nine years for another crime, and he never made headway in his fanciful quest to “find the real killers.” He died on April 10, 2024. He was 76.