Book Review | ‘California Against the Sea: Visions for Our Vanishing Coastline’ by Rosanna Xia

An Environmental Reporter Takes a Look at People Who are Doing Their Best to Deal with the Realities of Rising Sea Levels

In California Against the Sea: Visions for Our Vanishing Coastline, Rosanna Xia, an environmental reporter for the Los Angeles Times, writes: “When talking about climate change solutions, most actions fall under one of two categories: mitigation (reducing the rate of global warming) and adaptation (adjusting how to live with these hazards).” She notes, “Much of California’s climate change policies have centered on the former,” and it’s safe to say that mitigation is likely to be the first thought that comes to mind to the average person petrified by impending climate disaster. Indeed, to think first of adaptation may feel like giving up before the battle has been lost.

However, Xia’s book deals with realities, not fanciful hopes. She argues “the hard truth” is that “Even if the entire world stopped emitting carbon dioxide tomorrow, the sea will continue to rise for decades.” She likens this nasty forward movement to “putting the engine of a speeding ship abruptly in neutral: Existing momentum will continue to push the vessel forward until it finally slows down.” Like the many climate experts she interviews, Xia believes both mitigation and adaptation are vital, but California Against the Sea is under no illusions: Ultimately, the sea is going to win.

In fact, of course, the sea has always been the winner when it comes to California’s coast. Extensive modern settlement of the shoreline coincided with “a remarkable moment in history when the sea was at its tamest.” Now, though, in addition to human-caused climate change, “the mighty Pacific” has arrived at “the final years of a gentle but unusual cycle that had lulled dreaming settlers into a deceptive endless summer.” In short, if things look bad now, they are only going to get worse. Still, California Against the Sea does not wallow in despair. Perhaps the most crucial word in the book’s subtitle is the preposition: These are visions “for” our vanishing coastline, not “of.” As such, Xia seeks examples of Californians who are doing their best to deal with the realities of sea level rise. We meet Sara Cuadra of the Bay Foundation at Point Dume in Malibu, who pulls up the roots of the harmful invasive ice plant and sows seeds of “fiercely stubborn perennials” like red sand verbena. “For Cuadra … the sand is her palette, the pristine beaches her canvas for a different, more resilient landscape that beachgoers could learn to love.” And up in the salt flats at the southern end of the San Francisco Bay, long-time homeowners in the San Jose neighborhood of Alviso work to roll back the pernicious influence of industry and restore the wetlands, despite the complicated legal and ethical decisions involved.

Certainly, some areas present more dire problems than others. In a chapter entitled “Overlooked and Forgotten,” Xia speaks with residents of working-class Marin City and Deep East Oakland, who continue to suffer from ill-advised attempts to build atop and against the coast’s natural shoreline. Xia suggests that authorities may find it easier to ignore areas that have not been extensively studied, but “just because there isn’t data proving something needs fixing doesn’t mean that everything is okay.” Meanwhile, the largely affluent citizens of Pacifica, south of San Francisco on the Peninsula, struggle to keep their municipality from crumbling into the ocean. Despite all the money and effort the community has spent on retaining their land, “Their beloved town was built on an edge that nature wants back, and now they’re paying the price to hold the line.”

The book’s final chapter, “Bridges to the Future,” focuses on Gleason Beach, just north of Bodega Bay. Here, “Sand only emerges in the lowest of tides. Bits of concrete and rebar are all that remain of 11 clifftop homes that once faced the sea. A graveyard of seawalls, smashed into pieces, litters the shore.” But that grim picture is just a tease. It turns out that some of the land is being returned to the Kashia people, with the idea that the current generation’s “grandchildren, their children, and one day their children’s children will finally learn the ways of this coast. They can attend to the trees and re-balance each grove, and answer the ocean whenever it calls.”

It would have been nice to have had a chapter on California’s rocky and rural far North Coast — Fort Ross, 15 miles past Gleason Beach, is as far north as Xia ventures in any detail — but that’s a small quibble with a book that should be read by everyone who lives along California’s coastline, and everyone who cares about this jagged, unpredictable marvel of a landscape, one of the great natural wonders of the world.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

Premier Events

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Wed, Jan 22

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Talk: “Raising Liberated Black Youth”

Sun, Jan 26

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

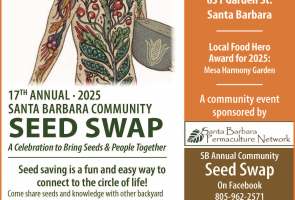

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Thu, Jan 30

8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31

9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08

12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Adrien Brody and Guy Pierce

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Wed, Jan 22 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Talk: “Raising Liberated Black Youth”

Sun, Jan 26 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Thu, Jan 30 8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31 9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08 12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.