Moving Life in the Projects Saga, and Much More on the SBIFF-scape

SBIFF, Day Two, on the Town and in the Cine-field

SBIFF, Day Two, on the Town and in the Cine-field

And the award for at least one of the smartest, wittiest award recipients in SBIFF history goes to … Robert Downey Jr., who held the room of the Arlington Theatre in epic fashion last night. The brilliant actor whose career has had its ups and downs and downs and outs proved to be alternately humble and mock-cocky, self-effacing, and appreciative of his current good life as a family man. In a full-bodied tête-à-tête with Leonard Maltin, Downey Jr. was both off script and on point. In short, he rocked (see Leslie Dinaberg’s report here).

His career in filmography is so crazily varied that it made sense to have two pals/presenters on hand for the Modern Master award occasion, starting with Rob Lowe, whose connection goes back to high school in Santa Monica and includes membership in the ‘80s Brat Pack scene. As Lowe quipped, his friend “met the challenge of overcoming addiction and the brat pack.” When talking about his sodden, drunken role in David Fincher’s brilliant Zodiac, Downey commented “I might have become that character if I hadn’t quit drinking and using.”

Downey Jr. recalled coming to the Montecito Inn during his prep work for one of his finest roles, Charlie Chaplin, who famously stayed at the Inn. He remembered telling the director “I’m going to become Chaplin. This will be my make-or-break role,” adding that “Hollywood — it can be a hard knocks space.”

More recently, Downey’s fascinating and self-searching pandemic project was Sr., a delightfully eccentric documentary about his iconoclastic filmmaker father Robert Downey Sr., of Putney Swope fame, who was dying at the time. Jr. described this filmmaking process as “very surreal. I think of it as the beginning of this new phase.”

And of course, the very reason for his timely Modern Master award at the Arlington was his role in Oppenheimer, in his potent Oscar-nominated supporting role as sparring partner of the titular performance of Cillian Murphy, also on hand to present accolades and a shiny trophy to his comrade.

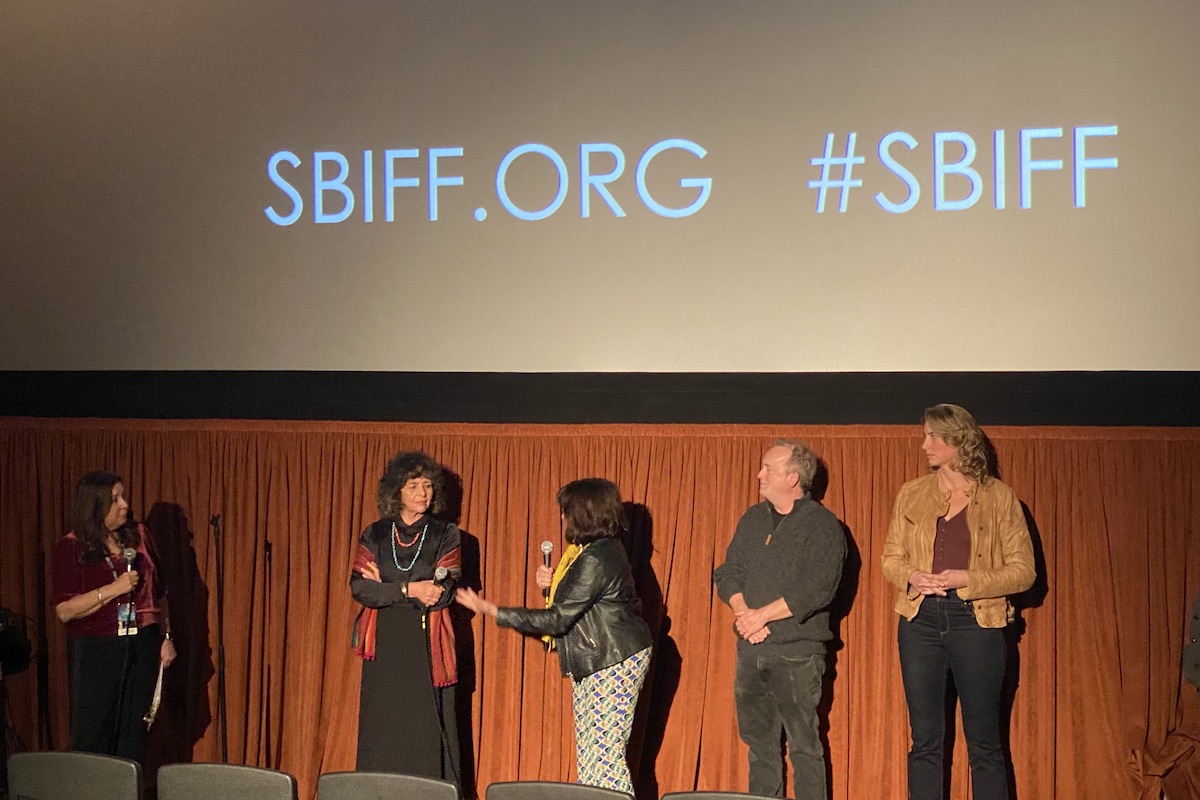

Interestingly, just prior to the Downey night out, a packed house saw the documentary First We Bombed New Mexico, a sobering and powerful talk about the ongoing dark legacy of radiation related cancer in the area around the atom bomb’s first blast in New Mexico and the impassioned activist struggling to bring the tragedy to public —and governmental — light. In a post screening A&A, director Lois Lipman made the salient point that “the huge success and popularity of Oppenheimer has put a lens on the subject. The question is: if the cloud went up, what happened when it came down?”

Clearly one of the best of fast titles this year has a strong link to Black History month, but with a unique time-and-place factor. Minhal Baig’s masterful, sweet, and unexpectedly poignant We Grown Now takes place in the legendary and sometimes infamous Cabrini-Green housing project in Chicago, circa 1992. The massive housing project, which became perhaps the largest in the world and occupied mostly by impoverished black residents, launched as a worker housing mega-effort in the 1960s and was demolished by 2011. Starting in the early 1990s, mayor Richard Daley began a ruthless campaign, waging war on drugs and crime in the project but with collateral damage on innocent families living there.

And it is a tale of innocent youths and family that warmly radiates throughout the film, in stark contrast to Hollywood’s stereotyped betrayal of black urban lives on the edge. Instead, we are led into the good-hearted formative lives of two pre-teen friends, still at an age of wonder and discovery despite the dire circumstances they live in. Our main protagonist lives in a nurturing family nest, guided by his loving and protective mother and wise grandmother, who was part of the Great Northern migration to Chicago from the racially volatile Mississippi.

We Grown Now is also an unusually meditative and sensual film, with rapturous visuals, lingering shots autumnal interiors, and the peaceful sonic coating of Jay Wadley’s minimalist score. No Uzis were used in the making of this film, although we are given hints of violence on the fringes — some from intrusive police — and the chronic low rumble of urban noise in the background. In the foreground are inspiring washes of hope and humanity. This too is an important slice of black history.

Whatever else might say or think about the British film Wicked Little Letters, it contains the best fecking cussing of the festival. And one of the great pleasures is hearing said expletive outburst emanating from the mouths of the always charming Jessie Buckley — a true pro — and the later-blooming, if awkward, cussing queen Olivia Colman.

Based on the true story of a mysterious campaign of obscenity-laced letter-bombing in Littlehampton, England, director Thea Sharrock’s film takes great and naughty delight in of such opposites as proper British and good Christian uprightness and wanton vulgarity. Buckley plays an Irish emigre, with daughter and black beau in town, and her guff-resistant frankness creates tensions in the neighborhood, esp. her Bible-righteous neighbor Colman.

Feminist elements sneak into the picture, which lapses into a whodunnit gone to trial, losing its sting and tang. But do stay for the plot twists and expert ejaculations of expletives.

Fri, Dec 27 6:00 PM

Solvang

Fri, Dec 27 9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Sat, Dec 28 7:00 PM

Lompoc

Sat, Dec 28 7:00 PM

Carpinteria

Sat, Dec 28 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Sat, Dec 28 9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Tue, Dec 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Tue, Dec 31 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Fri, Jan 03 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Sun, Jan 05 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Please note this login is to submit events or press releases. Use this page here to login for your Independent subscription

Not a member? Sign up here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.