UC Santa Barbara Scholar Ingrid Banks Discusses the Controversy Over AP African-American Studies

The History of Black Studies, the College Board, and Why Intersectional Blackness Matters

This article was originally published in UCSB’s ‘The Current‘.

The controversy around the College Board’s A.P. African-American Studies Course, which was targeted by Republican politicians in Florida seeking to restrict its contents, resulted in a version that made optional several key concepts and areas that were initially part of the core curriculum, including critical race theory, structural racism, intersectionality, Black queer theory and Black feminism, among other issues. Studying the Black Lives Matter movement, which helped make the course a reality in the first place, was also deemed optional. The most recent version, released in December 2023, reinstated the term “intersectionality” and sections on Black feminism and police violence.

But by relegating large swaths of Black experiences and histories, as explored in areas such as Black feminism and Black queer theory, to optional research topics, argues Black studies scholar Ingrid Banks, the College Board undermined the importance of centering intersectional Blackness in Black studies in general, and Black families in particular. Her recent article in the Journal of Family Theory & Review examines the controversy’s broad implications for family science and Black studies.

In the following interview, Banks, an associate professor of Black studies at UC Santa Barbara, discusses that article, the use of the term “anti-blackness” in Black studies, perceptions of Black families, and the importance of centering Black people’s experiences in understanding how racism manifests. The conversation also touches on the erasure of uncomfortable histories and the importance of open access to knowledge.

Let’s talk about the words you use in your discussion. Why do you use the term “anti-blackness” instead of “racism”?

Ingrid Banks: There’s a way in which there can be an appropriation of the understanding or definition of racism such that white elite men can be victims of racism. In this country, in Black studies, we center racism within the context of institutions and structures of power, such as schools, employment, media. We see images of Black people, for example, that continue to present blackness in negative ways. But when we talk about anti-black racism, that’s a way of centering Black people and really understanding the history of anti-blackness that goes back to slavery because throughout this country’s history, there’s never been any kind of move by this country to deny white people as a group access to social, political and economic rights because they are white.

For example, it wasn’t just white men who were storming the capitol on January 6. There were also women and folks of color. You don’t have to be white to be committed to or support the system of white supremacy, but there’s this idea of “white grievance” and “white fragility.” But again, white people have enjoyed access to social and political rights in this country in ways that Black people have not. So that’s why in Black studies we actually talk about anti-black racism. But as a Black studies scholar, I understand that even when I just speak on institutionalized racism, again, we can look at how Black and brown and Native Americans and Asian folks have to deal with particular things that speak to migration, immigration and so forth.

In your article you say that “the policing of Black families and Black studies go hand in hand through an explicit attack on intersectional blackness.” Discuss what you mean by that and how it can help us understand the recent controversy about A.P. African-American Studies.

Ingrid Banks: In the article, I discuss how anti-blackness is not only central to how the United States views Black families and Black Studies, but how anti-blackness intersects with other key social forces such as gender, sexuality, age, disability, ability, religion and more, to form what I term “intersectional blackness.” I actually use the AP African-American Studies course as a case study, if you will, to show how Black studies as a discipline and the perception of Black families are maligned.

The Florida Board of Education and Governor Ron DeSantis stated that the AP African-American Studies course did not meet the standards of something that had academic merit. It was the same old narrative about topics such as intersectionality, critical race theory, Black queer theory and Black feminism. The College Board made Black feminism, Black queer theory, Black Lives Matter and studies on the carceral state or prison studies optional categories for students taking the AP African-American Studies course

I thought about this and I was like, ‘Wow.’ Look at the outstanding work that Black queer theorists and Black feminists have done within Black studies to center the family and yet here, families that are seen as non-normative, such as LGBTQ families, they won’t fit into Black studies. Remember, going back to the enslavement period, Black women have historically been stereotyped as bad mothers. So what I try to do is make new connections by asking what does the AP African-American Studies controversy have to do with Black families? We can see how it has something to do with Black studies. But I think that I even shed light on the way in which the College Board really didn’t know the history of Black studies.

The College Board was very intentional in calling it an “African-American Studies” course. But then it was presented as an African-American history course. African-American history is not a general African-American studies course, though African-American history is an important part of an Introduction to African-American studies course.

Tell us about how the discipline of Black studies came about and its history.

Ingrid Banks: There’s a whole history of the institutionalization of Black studies in 1968-69 at San Francisco State College. My argument is that the College Board missed an opportunity to understand the history of how Black studies enters the university, enters the college curriculum, but also enters as a discipline in academia, even though there are scholars from different disciplines that do Black studies.

We have a discipline. We center social justice. We actually understand the importance of critical thinking. We critique the European-centered model of knowledge and education. And we’re not saying that we want to get rid of it, but when it is exclusive, then we must say, ‘Hey, there are other histories and experiences that must be centered within a liberal arts education and even within the context of just knowledge and knowledge construction.’ We critique the types of myths about, for example, Black culture as being deficient, inferior, dysfunctional, non-normative, all of that.

Your research shows that Black families and Black family values are undervalued and ignored in popular culture whereas they must be at the center of Black studies. Help us understand that.

Ingrid Banks: Going back to the family, there is a historical understanding of the Black family as being non-normative. Black families need to mirror white middle class heterosexual families. This goes back to Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s report in 1965 when he argued that, ‘Look, the reason why Black culture is so out of whack is because Black men do not head families, meaning that the problem is the matriarchal structure of Black families.’

That’s problematic. Because it means Black men need to be “men.” They need to be patriarchs and take their rightful place at the head of Black families, and therefore the head of Black communities. But I completely reject that patriarchal structure. Because it’s not only oppressive to Black families but also to white and brown families to think that men, just because they’re men, have to head families and therefore, that women have to be passive members of families.

We have to think about the ways in which Black people have experienced unemployment. The rate for Black men in 1965 when Moynihan was writing his report was extremely low. He told Black men, ‘Go into the military, find some structure, come out, get a job, and take your rightful place as patriarchs in Black communities.’ Well, how does that happen in a context in which there’s high unemployment for Black men?

So there’s a way in which Black families are viewed as non-normative throughout history, but there’s also a way in which Black studies is viewed as non-normative when it becomes institutionalized on college campuses — because it came out of Black student demands. There’s a long history of folks on the outside shaping Black people’s lives, going back to slavery and Jim Crow segregation. I make these connections that, again, I certainly saw as a Black studies scholar, but because I was talking to an audience of family science scholars, I wanted to lay it out and also do some theorizing because I think the College Board had good intentions in terms of trying to democratize AP advanced placement courses. But in the end, they failed.

Today, they’re coming for Black studies but tomorrow they’re coming for other disciplines. Sure enough, AP Psychology, which was a long standing AP course, essentially violated Florida’s “Don’t say gay” bill. There were concerns that if LGBTQ studies or topics such as gender and sexuality were taught in AP Psychology, then the course would be banned. In fact, the folks in psychology were like ‘that means AP psychology has effectively been banned in Florida.’ Parents also got upset and said, ‘Wait a minute, our kids are signed up for this to get college credit, are they not going to be able to get college credit?’ And what does the College Board do? They stand up for AP Psychology. The very thing they didn’t do for the AP African-American Studies course.

Let’s make sure we understand. In order to talk about anti-black racism, and in order to talk about Black folks in the United States, you also have to talk about Black families and values. At the same time, Black studies is not just Black history. So while you might say that queer theory is not Black history, it is still a part of Black studies?

Ingrid Banks: The theorizing and language that I use is “intersectional blackness.” So we have to say that part of this problem is thinking about Black people’s lives as being shaped only by race. But George Floyd isn’t murdered simply because he’s Black or simply because he’s a man; it’s because he’s a Black man. Because of the intersection of race and gender. As Black women, we just don’t experience racism and we just don’t experience sexism. We experience both of those. There’s no space in between Black and women there.

My argument is that intersectional blackness matters in how we study Black people and Black families. Here you have this AP African-American Studies course that is supposed to reflect a college level course. So it should look like my introduction to African-American studies course that I teach. But if you are going to fringe Black feminism and Black queer theory, then that actually leaves out a more democratized understanding of Black studies — of Black families, of Black people in general, and of Black identities. Because Black people are straight, gay, lesbian, trans, non-gender conforming, all of that.

When the American Psychological Association responded to their own College Board controversy, they said, ‘Look, in the AP psych course, students have to study about gender and sexual identity, and that makes them better students and better citizens.’ I want that for students who are taking the AP African-American Studies course, too, as well as students taking my Introduction to African American Studies course at UCSB.

Premier Events

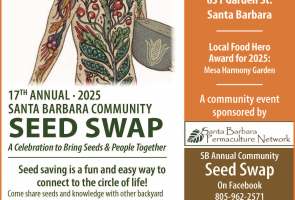

Sun, Jan 26

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

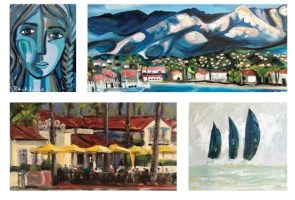

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sun, Jan 26

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Tue, Jan 28

5:00 PM

Zoom

Fire Safety Community Zoom Meeting

Thu, Jan 30

8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31

9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08

12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Adrien Brody and Guy Pierce

Sun, Jan 26 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sun, Jan 26 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Tue, Jan 28 5:00 PM

Zoom

Fire Safety Community Zoom Meeting

Thu, Jan 30 8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31 9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08 12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara