Mission Possible:

Returning the Kelp Forest

to Our Coast

Santa Barbara Fisherman Chris Goldblatt

Plans to Bring Back Reef Habitats

Around the Globe

By Callie Fausey | Photos by Chris Goldblatt

December 21, 2023

When I sat down to interview Santa Barbara–based fisherman Chris Goldblatt, I was expecting a conversation about the benefits of putting rocks on the seafloor to create reef habitats.

What I got instead, however, from the 50-year-old seafarer on that sunny morning in Goleta, was a Cast Away–esque survival story.

Ultimately, though, it still turned out to be about rocks and fish.

Sitting out on the Dean coffee shop’s patio, Goldblatt, wearing a T-shirt with the blue-and-yellow logo of his nonprofit, the Fish Reef Project, asked me, “Do you want me to go all the way back to the genesis?”

Maybe, unless you’re speaking to a Jehovah’s Witness at your doorstep, the answer to that question should always be: “Yes,” I told him, “go all the way back to the genesis.” And he did.

The Genesis

“I was in a horrible tragedy at sea in 2003,” Goldblatt began.

It was a cold November night, and Goldblatt and five of his friends were on a 50-foot speedboat heading to San Clemente Island, 50 miles offshore of San Diego.

Goldblatt was sound asleep when the boat accidentally ran into the towline of a tugboat towing a 300-foot petroleum barge. “The boat snapped in half like a toothpick,” he said.

Goldblatt and his friends jumped ship, and he found himself in freezing ocean water wearing only his underwear in the middle of the night. “It was the most horrifying thing you could ever imagine,” he said.

Everyone was banged up and bleeding, but alive. Finding a small escape raft, they climbed aboard and drifted all the way down toward Mexico until U.S. Border Patrol found them the next day, almost dead from hypothermia.

“But when you’re in a situation like that, and you’re basically just floating and waiting to die, you tend to make a lot of bargains. Right? There are no atheists in foxholes,” he said. “The deal I made was, if I survived, that I would spend the rest of my life trying to balance the equation of what I’ve taken out of the ocean.”

That was two decades ago, but it was that promise that sparked the Fish Reef Project — Goldblatt’s life’s work for the past 12 years.

Rocks = Fish

The Fish Reef Project, which Goldblatt founded in 2011, aims to replenish depleted reef habitat on the Central Coast and around the world by providing a crucial building block for kelp forests: a hard, rocky surface on the seafloor.

Kelp is vital for the marine ecosystem, offering fish habitat, reducing ocean acidity, supporting plankton, and mitigating beach erosion by softening the impact of ocean waves on the shoreline.

Coastal ecosystems, particularly fast-growing macroalgae like kelp, can sequester up to 20 times more carbon than land forests, an estimated 200 million tons annually. Despite some debate on kelp’s carbon output and overall climate impact, it remains crucial for marine health. But it is disappearing.

A marine heatwave from 2014 to 2016, coupled with a decline in sunflower sea stars, decimated more than 90 percent of California’s North Coast kelp. Sunflower sea stars were being killed off by a state-wide epidemic, leading to an increase in their favorite snack: kelp-eating sea urchins.

Southern California also faces severe kelp reduction — more than 75 percent in some regions — but largely due to pollution and overfishing in the past century.

Records from 1912 describe a thousand-foot-wide kelp forest extending from El Capitan to Rincon Point, which has nearly vanished, thanks to the damming of rivers, storms, and repeated droughts.

Phil Beguhl, chair of the Santa Barbara County Fish & Wildlife Commission, recalls admiring the massive kelp bed when he was younger, seeing it stretch from Campus Point for miles down the coastline.

However, the 1983 El Niño tore out the kelp’s massive anchors that would usually support new kelp growth after big storms. Only about 5 percent of the kelp recovered, Beguhl estimates. However, he thinks, “Thousands of acres of kelp could be restored by giving it some kind of substrate to grow on.”

Historically, creeks, rivers, and mudslides would flow into the ocean, carrying rocks, sand, and debris that would have replenished the foundation needed for kelp growth. Human activity and infrastructure, however, “choked off that supply of critical habitat for kelp to regrow our local ecosystem,” Goldblatt said.

Taking a stroll along the semi-rickety Goleta Pier, past pigeons and anglers, Goldblatt pointed out the city’s wastewater pipeline, submerged 90 feet deep and extending a mile offshore. It runs parallel to the pier, a dark stripe in the greenish-blue water. Looking down through guano-splattered planks, we could see seaweed swaying against the pier’s supports. Kelp had transformed the quarry-rock-covered pipeline into a vegetative runway.

Goldblatt explained, “The rest of the bay is just mud. But when you have structure, good structure, the kelp seeds find a way. I guess the reason I’m showing you this is, clearly, nature wants to participate. It just needs a vehicle.”

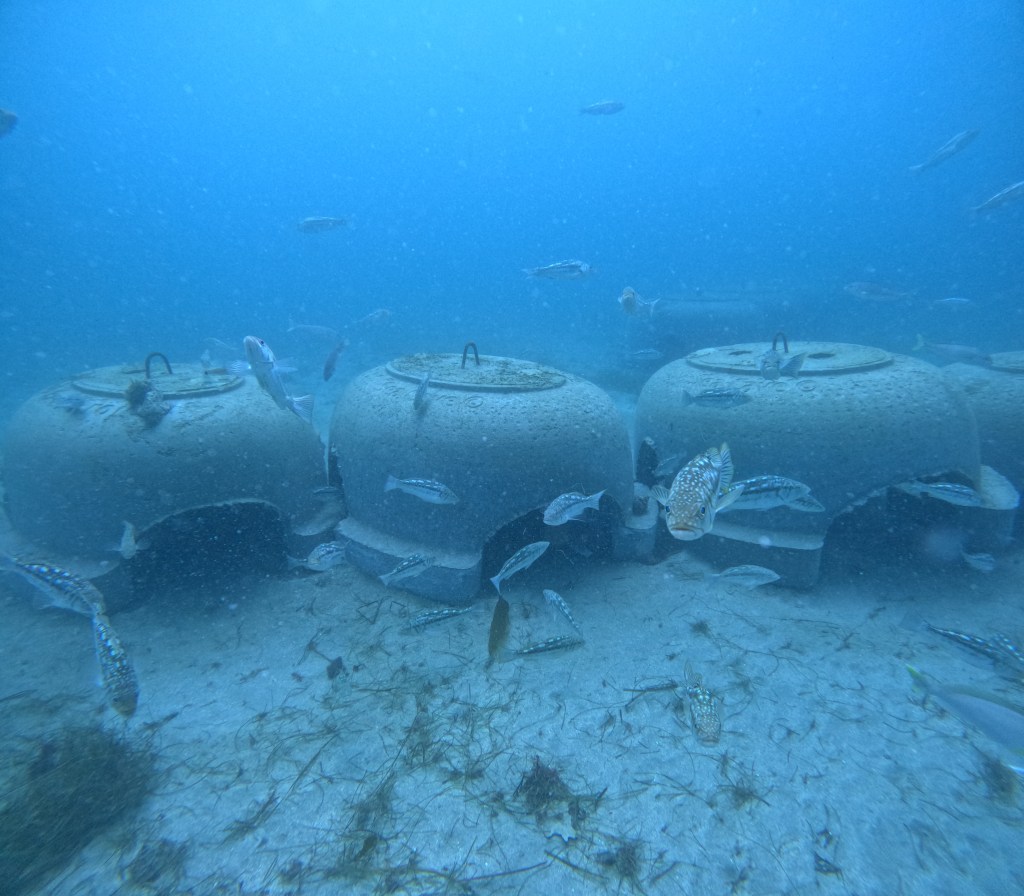

The Fish Reef Project is planting those seeds. That is, if you could call nearly 3,000-pound cement igloos “seeds.”

The massive cement units are intended to be artificial reef structures on the barren seafloor. Similar techniques are now being deployed in more than 70 countries.

Right here in Southern California, our coasts already host numerous artificial reefs, such as the SONGS (San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station) reef near San Clemente, built by Southern California Edison to mitigate the outfall from the nearby power plant.

According to Dan Reed, a UC Santa Barbara research biologist involved in the SONGS project for 30 years, most artificial reefs that are out there now were intended to serve as “fish-attraction devices.”

“People just throw junk, anything, out there to do this,” he said, “but California has much more rigorous laws governing what you can put in the ocean.” The Fish Reef Project will be creating a new kind of habitat in Santa Barbara County. Not a bad one, Reed said, “just different.”

Sea Caves

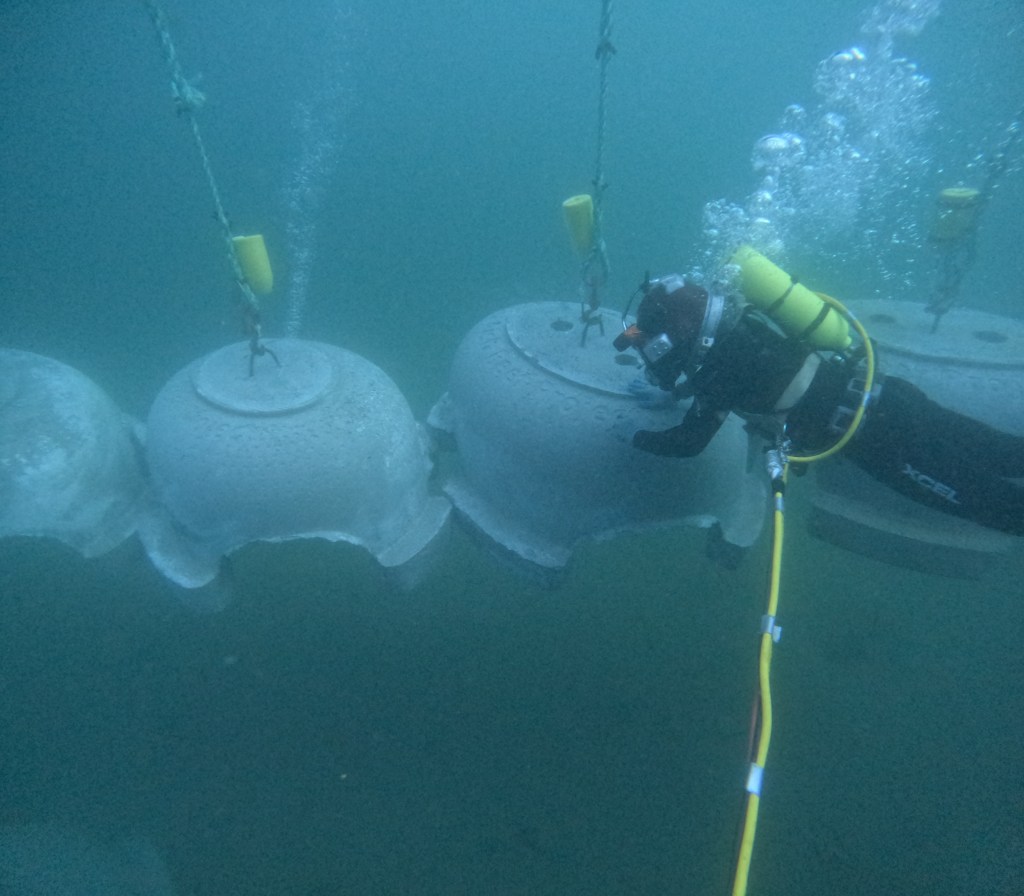

Although the Fish Reef Project originally employed “Reef Balls,” a product of the Reef Ball Foundation, to build the reefs, they recently shifted their focus to Goldblatt’s original design. Now they use their own, newly patented Sea Caves — textured concrete domes, resembling four-legged structures with a metal hook at the top, which rest on the seafloor.

Goldblatt and his team had to chemically engineer a concrete that matched the pH of the seawater so that sensitive kelp seeds had a better chance of germination. Designed with flat surfaces for holdfasts and inner chambers for fish habitat, they create a dynamic cave system for fish to populate and reproduce. After a few years, Goldblatt believes the structures will look and act entirely natural, supporting giant kelp growth for up to 500 years.

Tina Reef

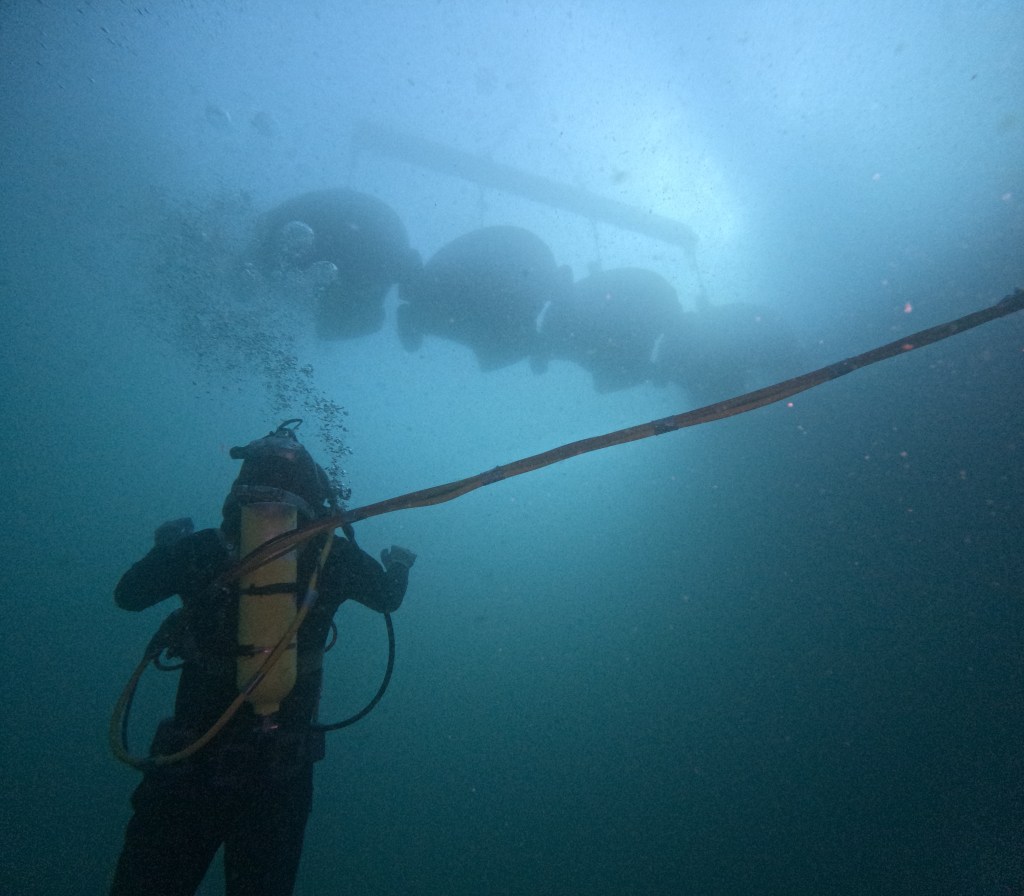

In August 2023, Fish Reef Project Mexico launched the first batch of 500 Sea Caves in the prime kelp-growing regions of Baja California, covering four acres of seafloor. They are the first of thousands, Goldblatt said, that will be produced at a modest facility his nonprofit built in Ensenada, Mexico. Using fiberglass molds, it turns out eight sea caves a day, six days a week.

Fish Reef Project Mexico is their biggest undertaking yet. The permitting process alone took more than a year. But it was worth it. In just seven months, the caves were covered in “thick, robust kelp plants … with abalone, lobster, calico bass, and giant black sea bass,” Goldblatt beamed. “We thought that would take five years.”

Fish Reef Project Mexico executive director Ulises Uribe, a 13-year veteran of the fishing industry, said that for now, the reef is off-limits to fishing while marine life continues to take hold. But he agreed that it’s showing great promise, with fish sheltering right away in the new caves.

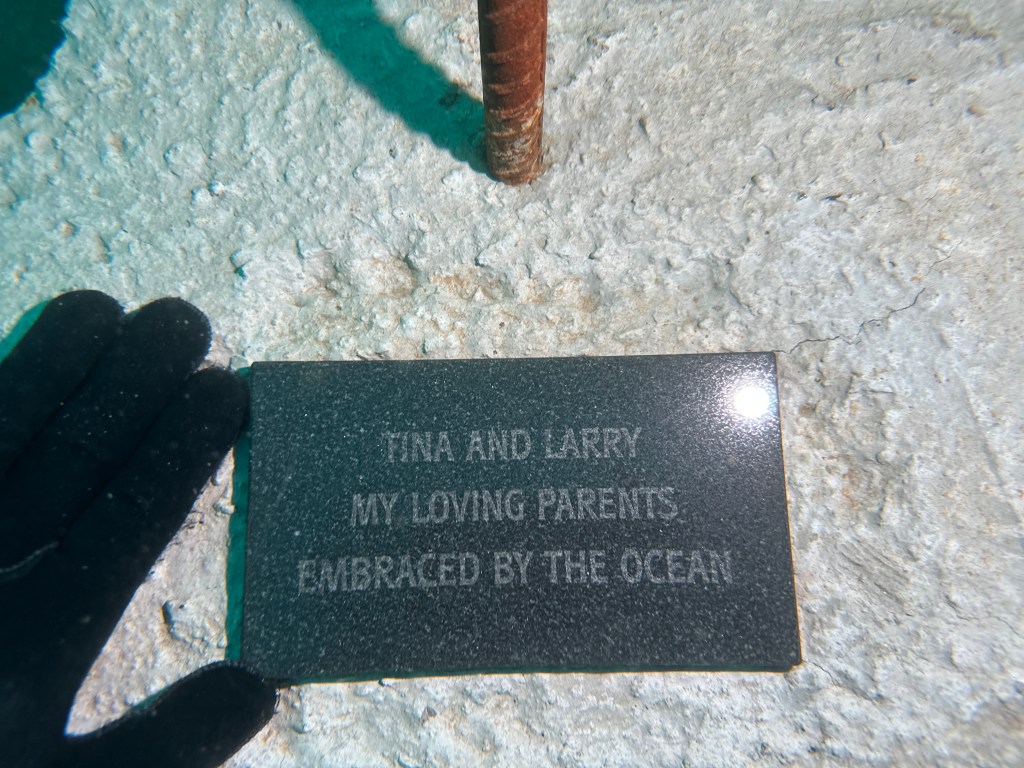

Goldblatt named the site “Tina Reef” after his late mother. He even put both of his parents’ ashes into a sea cave together, marked with a plaque in their honor.

“That’s how I memorialized them,” he said. “Hopefully they won’t fight.”

True Believers

Despite his traumatic boating incident, Goldblatt has had a lifelong love for the ocean. “My mom let me take a lot of chances that most mothers would never do,” he recounted. “As early as 12, I was working in an offshore San Diego tuna fleet. I bought my first boat when I was 13, doing laps around Catalina.”

He stayed on that course, gaining more than 35 years of experience, including earning a bachelor’s degree in Fisheries and Business from Humboldt State University. Somewhere along the way, he met the fishing buddies who’d become the “core group of true believers” in the project that was sparked by brainstorming during diving trips they took together.

Discussions around the emerging Marine Life Protection Act in 1999 prompted their focus on restoring and creating habitat in less productive and unprotected areas, according to Andy Taylor, the project’s marine biologist and equipment coordinator, who owned a dive shop in the Santa Barbara harbor for more than 20 years.

Goldblatt was known as an outspoken critic of state-sanctioned marine protected areas (MPAs) in Southern California. But since he has had time to study the MPAs, he has “seen their benefits,” though he still feels that “future MPAs should include the needs of subsistence fishing.”

He sees the reefs as “complementary” to MPAs, that they can alleviate fishing pressure, “unite the ocean community,” and offer vital habitat for small fish spilling over from MPAs to flourish.

A Rocky Start

Initially, the Fish Reef Project operated on unpaid 40-hour workweeks and a shoestring budget. They relied on self-funding, in-kind, and modest donations — the first of which, Goldblatt says, was $10,000 from the late SpongeBob creator Stephen Hillenburg.

“In the early years, it was a lot of people putting in their time for free,” said Taylor. “Even now, no one is getting paid too much. A lot of people are holding onto this dream and wanting to see it through.”

So far, the project — which has recruited professors, engineers, graphic designers, and construction workers — has spent about $1.5 million including for development, site surveys, prototyping, travel, permitting, reef construction, outreach, and deployment. “So we have stretched our funds like a rubber band and made every dollar count,” Goldblatt said.

In 2012, when the Fish Reef Project was barely a year old, they landed in some hot water for putting experimental Reef Balls off Hendry’s Beach without the necessary permits. “No doubt [Goldblatt] jumped the gun a bit,” the California Coastal Commission’s Cassidy Teufel told Indy reporter Ethan Stewart at the time.

During our interview, Goldblatt lamented the difficulty of navigating state and federal permits. He maintained that they thought the project’s actions were legitimate under existing aquaculture permits. However, the Coastal Commission opened an investigation when they found out about the reef balls.

“It was very complicated,” he said. “We removed and destroyed those units … and then that case was completely closed.”

Reel Results

In the years following the Hendry’s Beach hiccup, Fish Reef undertook small-scale projects in locations such as Lake Cachuma, San Diego, and South Carolina, and they even started to venture into foreign waters.

“Although it started locally, there was always an international side of it,” Taylor grinned. “Constantly brainstorming how we can help these very different types of areas, from a kelp bed here, to working with a local Girl Scout Troop at Lake Cachuma, to coral reefs in Papua New Guinea.”

In 2019, they deployed 21 reefs near that country’s capital, Port Moresby, where the aim was to rebuild coral beds for coastal communities that Goldblatt explained depended on subsistence fishing for a living. Today, the thriving reef system, captured in video footage after only 2.5 years, hosts vibrant marine life, including algae, coral, and clownfish.

Similarly, Sea Caves deployed in 2021 by the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources survived a hurricane and hosted barnacles, corals, and marine algae within 3.5 months of being placed off Charleston.

Even the illegal reef balls off Hendry’s Beach were “crawling with life” within a month, Goldblatt said. Footage of the two units on Fish Reef Project’s YouTube page revealed kelp-covered structures, adorned with starfish and complimented by a “halo” of life after 18-19 months.

Goleta Study

Goldblatt called Tina Reef a “great beta test” for their Santa Barbara plans. Goldblatt is securing permits, including from the Army Corps of Engineers, California State Lands Commission, Coastal Commission, and Department of Fish and Wildlife, for a five-year pilot project in Goleta Bay — the “Goleta Kelp Reef Restoration Project.”

“I think it’s probably easier to run for governor of California than it is to make a reef in California,” Goldblatt ventured.

Standing on the Goleta Pier, he pointed to the heart of the bay. “That’s about where the 16 sea caves are gonna go,” he said. They plan to deploy them sometime in January.

This year, the California Coastal Commission voted unanimously to waive the Coastal Development Permit requirement, and State Lands approved a general lease for the land where the sea caves will be deployed.

If proven effective, they will apply for permits for a permanent, 65-acre project, retaining the study reef as a starting point. If they’re unsuccessful or lack funds for expansion, they’ll have to remove them. Given the rapid success of the Baja reefs, though, Goldblatt remains optimistic.

The pilot project will cost about $300,000, but the full-scale 65-acre project would approach an estimated $20–$25 million. “For the price of a decent home in Montecito, the entire community can have a good portion of historic kelp forests back,” Goldblatt offered.

Community Support

Regional regulatory agencies and the environmental community have finally begun to embrace the project. Letters of support have come from all corners of the community, including the City of Goleta and former state senator and current Independent board member Hannah-Beth Jackson.

Fish Reef has been involved in outreach at schools, museums, and community events for years, but just this month, the MOXI museum debuted a 90-day exhibit dedicated to the nonprofit and its Sea Caves.

Over the past year, the Santa Barbara County Fish & Wildlife Commission and the County Board of Supervisors approved a total of $69,500 in grants for the project. The commission’s Beguhl has been a longtime fan, calling the project “one of the most potentially effective environmental improvements that could be done anywhere around Southern California.”

Supervisor Laura Capps, whose district includes the bay, emphasized the importance of kelp as the forest of our oceans. “It’s my district,” she said, “but there was unanimous support and enthusiasm from the board.”

Various funding sources, such as the Santa Barbara Foundation and Deckers Brands, also contributed relatively modest grants to the project, considering the work that lies ahead. Goldblatt says he makes up the rest personally as needed, but 2023 has been their most lucrative year, “with about $200,000 donated now that Goleta permits are coming to fruition.”

Mitigation Money

The Fish Reef Project has been building a “blue carbon” bank to allow industries to buy carbon offsets based on measurable carbon sequestered and biomass created by the reefs. The International Marine Mitigation Bank, which Goldblatt founded in 2016, aims to use the reefs as a mitigation option for future deep-sea mining operations.

“Deep-sea mining is a major upcoming means for the world to access vital minerals, mainly for electric vehicles, but it is not without impacts or controversy,” said Goldblatt, who has been a deep-sea mining consultant through GLG Insights since 2019.

Deep-sea mining is expected to have severe environmental impacts, including habitat removal, the release of heavy metals and other toxic compounds into the ecosystem (with the potential to contaminate seafood), and noise pollution, to name a few.

Since 2015, the Fish Reef Project has been a permanent observer on the United Nations International Seabed Authority, which was established to regulate deep-sea mining operations in international waters. They’ve advocated for regulations mandating seabed restoration and social mitigation projects — like rebuilding coral reefs — after mining for metals on the seafloor.

In a 2016 interview with ECO Magazine, Goldblatt revealed plans to create reefs at the nearest points of land adjacent to “Solwara-1, the first deep-sea mine to go into operation owned by Nautilus Minerals in Papua New Guinea.”

Ultimately, no deal was made with Nautilus, and Goldblatt told me the project is now defunct. However, as Goldblatt told ECO Magazine, they moved ahead with the reefs anyway, storing “credits in the bank that can be used for other purposes,”.

Branching Out

The Fish Reef Project has explored potential reef installations in locations from Hawai‘i to Jamaica and is actively working on projects along the African coast and in Bangladesh.

They also have big dreams of converting California’s abandoned oil rigs into reefs and are seeking funding for the Rincon Island (Fish Reef Island) Climate Mitigation and Reef Research Center as a means to repurpose old oil infrastructure.

“It’s all in the works,” said the Fish Reef Project’s Director of Construction Lonnie Nelson. “It’s a slow process. If we had funding and a bigger staff, it’d be a lot further along than it is. The fact that it is this far along, with the limited resources we have, is a feat in and of itself.”

In Bangladesh, marine scientist Mahbub Alam reached out to Goldblatt on LinkedIn, citing the potential for reefs to mitigate climate-change impacts and renew fish populations, which would support the small country’s coastal communities.

Similarly, in Senegal, Executive Director Hamet Owens-Ndiaye has been working to obtain permits and finances for the initiative over the past year. He met Goldblatt at a UN conference in Qatar in March, and recognized that they “have the same vision.”

Owens-Ndiaye said that not only will it alleviate some of the challenges local fishermen are facing, but “it will also be empowering women because women are the backbone of the fishing industries” in Africa.

“This is the kind of project that will be extremely important for us,” he said, smiling. “It’s doing a small part. But, you know, a small part can create a great impact on our society.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.