Santa Barbara Teachers Close Their Doors in Protest as Labor Negotiations Heat Up

S.B. Teachers Association Members ‘Working to Contract’ to Put Pressure on District for Better Pay

Salary negotiations between the Santa Barbara Unified School District (SBUSD) and Santa Barbara Teachers Association (SBTA) enter round two on Tuesday, November 28.

The first round of bargaining prompted teachers to close their doors in protest nearly two weeks ago.

On Wednesday, November 16, these Santa Barbara Unified educators, many for the first time in their career, began doing the bare minimum of what’s required of them — no more before- and after-school hours, no more student lunches in the classroom, no more letters of recommendation, and no more weekends spent lesson-prepping.

They described it as a kind of “last resort” to persuade the district to heed their demands for better pay, benefits, and working conditions.

“This is meant to demonstrate that teachers go above and beyond what they are meant to do contractually,” said SBTA president Hozby Galindo, a math teacher at La Cumbre Junior High for 19 years.

“It’s so people start to realize, ‘Wow, teachers do a lot more for us than we ever imagined.’”

First Day of Negotiations

Teachers’ “working to contract” is in response to the district’s seemingly laissez-faire attitude at the bargaining table. During the first round of contract negotiations on November 15, teachers asked for a 20 percent increase across the entire salary schedule in the 2024-2025 school year.

The district, SBTA says, did not come prepared with a counter-proposal as they had hoped.

“It was disappointing,” Galindo said. “We’ve made it clear that teachers do not feel valued, and when they’re not valued, teachers go elsewhere. At the end of the day, the students are the ones who are hurt.”

The district estimated that the cost of the proposal would be $20 million for the bargaining unit. “SBTA stated its belief that the District could afford this proposal through spending down reserves (which are one-time funds) and making potentially major changes in District spending,” the district’s negotiations update read.

What the district did bring to the table, however, was a health benefits proposal, offering to increase coverage from 40-60 percent to 75 percent of premium costs.

According to the district, that would save employees around $1,020 to $9,370 annually, depending on household sizes, and would cost an estimated $3,081,422 to cover only the SBTA bargaining unit. There are about 600 SBTA unit members — out of around 850 certificated non-management staff — covered by the district’s insurance.

The SBTA bargaining team also proposed to maintain reduced class sizes, at an estimated cost of $6.2 million from the district.

In the first negotiations update sent on November 15, the District shared its “Core Values in Negotiations,” which includes “support quality educators to promote success for students.” The SBUSD Board of Trustees highlighted this in a letter to all district employees on November 20.

“Both the Board and District leadership are fully aware of the vital need to attract and retain dedicated teachers and staff to provide excellent educational programs to students,” the letter reads.

It continues to say that they are informed about the proposals exchanged in negotiations and will “provide clear direction to District leadership and our negotiations team to bargain in good faith. We are all unified in this effort — the Board, the Superintendent, District administration, and the negotiation teams.”

They acknowledge the “increasingly competitive market to employ and retain educators in all districts across the state as more leave the profession or move to less expensive locations,” adding that they wish to complete negotiations in “a timely manner.”

“Be assured that we see you, we hear you and we will do our best to reach a mutual agreement on compensation while maintaining the fiscal health of the District,” the letter concludes. “The Board believes that any agreement reached must benefit the students, staff and community we serve now and well into the future.”

Apples Won’t Fix This

Stress and burnout seem to be the most common symptoms of being an educator in Santa Barbara.

From speaking with teachers around the district, other symptoms include: living paycheck to paycheck — and with roommates/parents — even with master’s degrees displayed on their walls; taking care of students with special needs even if they are not trained to do so; working up to 60-hour weeks; and spending full days in sweltering classrooms without A/C when Santa Barbara heats up.

One 4th-grade teacher from Harding University Partnership School (who requested to remain anonymous) said she bought an A/C unit for her classroom using money from her own pocket. It was fine last year, she said, but this year, she and other teachers who had done the same were told to remove them because they were “overloading the circuits.”

“It’s harder to concentrate when you’re too hot,” she explained. “You’re not happy. Kids get antsy.”

But when teachers have asked the district for air conditioning, they’ve been told that, since many of the schools are so old, it’d be too expensive to update the electrical circuits.

“I’m disappointed that we as a community aren’t taking better care of our teachers,” said Jessica Johnston, a parent of elementary-aged children in the district. “Asking teachers to work in classrooms that are 85 degrees or worse is unacceptable. … We need to do better, a lot better.”

In addition to wages and weather, the shortage of paraeducators in the district has overwhelmed teacher caseloads and pushed educators to their wit’s end. Numerous teachers told the Indy that they have students with “severe behavioral problems” in their classrooms who are not receiving the support they need, forcing teachers to step in where a paraeducator should be.

These students, according to teachers, “destroy classrooms” and “disrupt and upset other students” because they do not have access to the individualized support and attention they need.

“I’ve seen a student injure another student because he did not have a paraeducator with him,” said one 4th-grade teacher who’s taught in the district for five years. “My husband thinks I’m crazy for wanting to keep teaching. I don’t know how much longer I can do this.”

Galindo said that SBTA intends to negotiate in good faith with the district. But, if for some reason they come to an impasse, they’ll have to involve a mediator. There’d be a long process before they could seriously consider a strike, he said. “We’re going to negotiate in good faith, and we hope the district comes to the table and does the same.”

Teachers did receive a 4 percent raise last year, but that wasn’t enough, the union said. “It feels like a Marie Antionette ‘Let them eat cake’ type of thing,” said Dee Carter-Brown, a 2nd-grade teacher at Harding.

“Teachers shouldn’t have to take a vow of poverty to work here,” she continued. “Plus, stressors, like around rent, find their way into the classroom. We have a ‘soft job’ — you have to have an emotional connection to teach. It’s hard not to take things personally and let your feelings follow you into the classroom.”

There’s no doubt, then, that working to contract, or doing the bare minimum, will be difficult for many of these teachers. “Probably one of the hardest things a teacher can do is say no to a student,” Galindo said. “We work from the heart; we want to make sure we show up for our students. This will not be easy.”

Heated Boardroom

Even students are fed up. Students from elementary to high school stayed up on Tuesday night, November 14, to tell the school board how the issue of teacher salaries and turnover trickles down to the campus, the classroom, and even the playground.

“As a student myself,” stated a young girl named May, standing on a chair to reach the podium,

“the playground feels unsafe because there are not enough yard duties because you guys aren’t paying them enough, and people are getting bullied.”

When former student boardmember Kavya Suresh approached the podium, she was met with smiles from the board. But she wasn’t there for niceties.

“We all inherit the stress and trauma of each other; if our teachers are stressed, we feel it as students,” Suresh said, speaking on behalf of her peers at San Marcos High School. “So how can we take care of each other?”

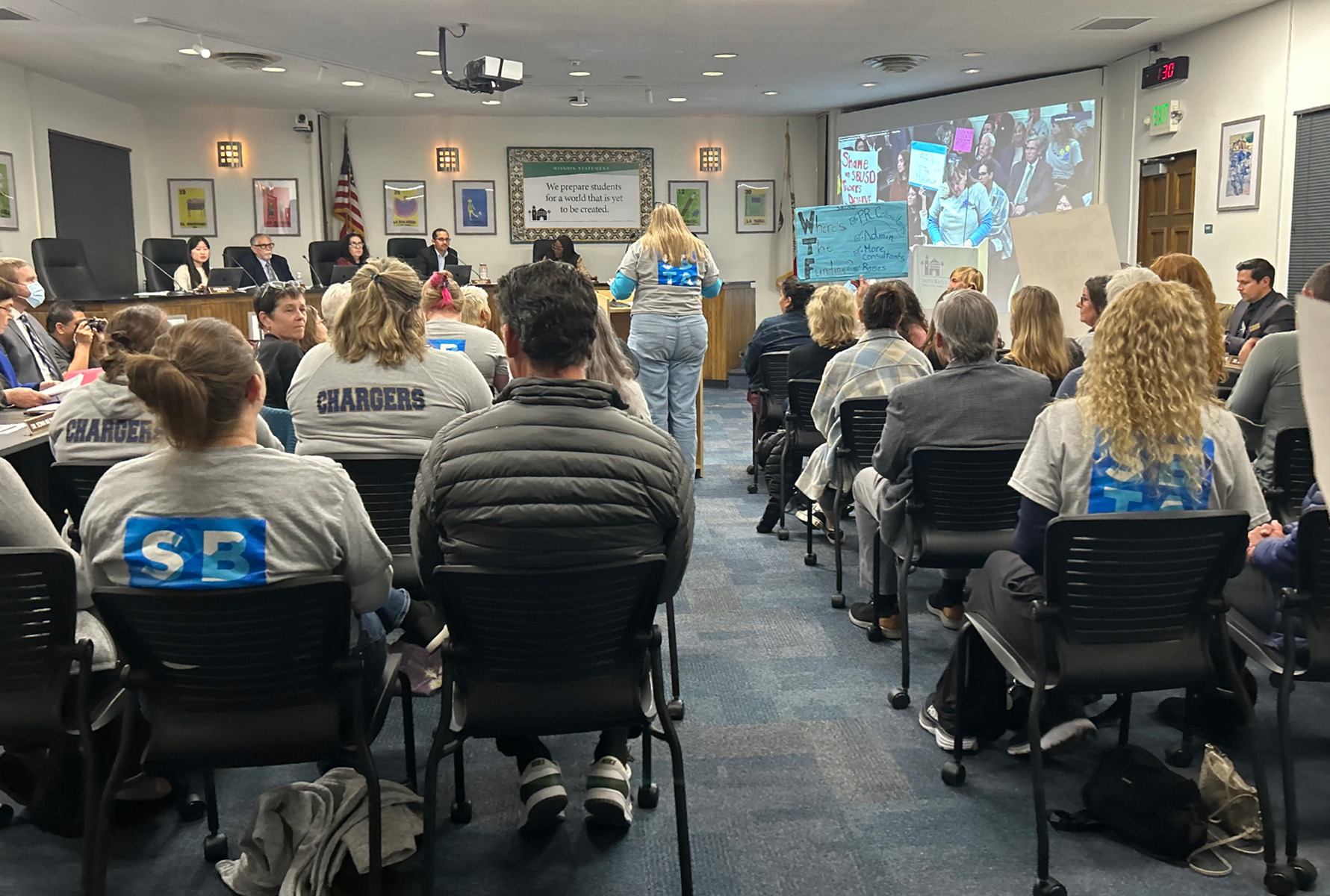

On the night before the first day of contract negotiations, a group of around 200 librarians, teachers, students, and parents crowded the floor and watched through windows in the most well-attended board meeting in recent memory.

The energy of these teachers, many at the ends of their ropes, was palpable. The sounds of bells and cheers echoed throughout the building when a speaker made an especially poignant comment, no longer observing formalities.

Boardmembers made repeated, futile requests for attendees to not cheer and “respect the meeting.” But tensions were high.

Teacher Leo Borden passed the 90-second mark allotted for public comments. And then he kept going. He addressed the board directly, pointing his finger and saying, “No one sitting in front of me truly cares about the people standing behind me.”

“We have a superintendent who has driven off every member of the cabinet, except for one,” he continued. “More troubling is the annual exodus of teachers — more than 100 this past year and 100 more before that.”

With support from the crowd, he raised his voice to speak over the boardmembers’ “thank-yous” to try to get him to step down. “Is somebody calling time, or announcing 30 seconds, when we are grading papers on a Saturday afternoon?” Borden asked.

“I am sorry for my transgression,” he concluded. “Maybe I will ask the state for a waiver.”

The mantra for the night was “$6.7 million” — representing the amount by which the district failed to meet state requirements for teacher salaries last school year, requiring them to seek a waiver from the state. They blamed it on one-time COVID-19 funds and expenditures — from 2020-2024, the district received $60,513,658 in those funds.

Kelly Savio, an English teacher at Dos Pueblos, said she was “deeply troubled” that the board approved a waiver that “told our district that it was okay to ‘accidentally’ underpay our staff by almost $7 million.”

“And you did so after asking exactly zero questions about how that happened,” she told the board. “And yet, you asked several questions about the cyber security insurance policy that was presented at the same meeting.”

Jose Caballero, a teacher at Santa Barbara High School going on his 21st year, was one of many teachers who wrote a letter to the Santa Barbara County Education Office in opposition to the waiver.

“I’m sure you know that S.B. Unified has been, for many years, flirting with the absolute rock bottom of what the state requires; while other neighboring districts are investing 60%, 68%, even 73% of their budget in their teachers,” Caballero wrote.

“However, you might not know that teacher morale in our district is at all-time historic lows, and everyone in our community knows that the cauldron of dissent is about to boil over,” he continued. “You absolutely can not allow our district to make excuses for underfunding our teachers. There can be no education without our teachers, and I need you to hear that our teachers are at the absolute ragged edge.”

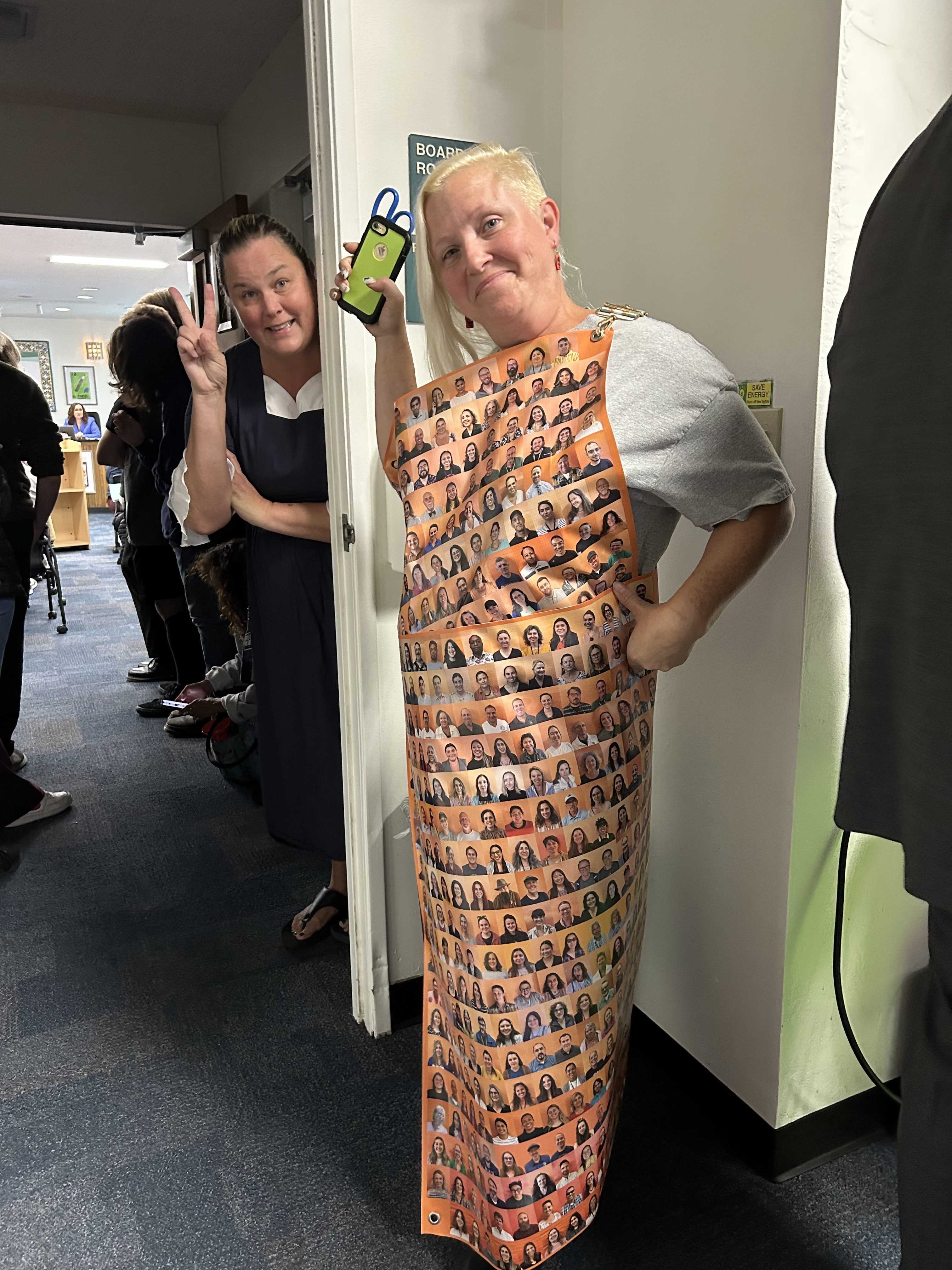

Out of the 724 teachers in the union, 611 teachers had their faces printed on a photo petition, which was made into a three-foot-by-six-foot banner to present at the school board meeting.

However, Superintendent Hilda Maldonado and board president Wendy Sims-Moten called the sign a “safety issue,” implying that it could be a fire hazard. In response, teacher Kate Lambert wrapped the banner around her body to speak to the board on November 14.

“Thank you for letting us know that having a banner would be a fire hazard,” said Lambert, a teacher at Santa Barbara High School for the past four years. “It is not, but we took it off of our post, we offered you lots of ways to bring it in, and you still said no, but I am wearing it, and if I have to leave, that’s just fine.”

Galindo said the banner is supposed to represent the “solidarity and unity that teachers have,” but it’s also meant to garner community support during the bargaining cycle.

“We need the community to show up for us — that makes a huge difference,” Galindo said. “We’re definitely asking for community support, so teachers can afford to live where they work, and so they don’t have to make the choice between paying bills and buying food.”

San Marcos High School science teacher Sammi Lambert — who was named a 2023 “Distinguished New Educator” by the Santa Barbara County Education Office — says that out of the 11 educators from S.B. Unified that have been presented with the award over the past decade, only four are still teaching in the district — including the two awarded this year.

On the agenda that night, somewhat ironically, was a proposal to offer an early retirement plan to educators to save the district money, as well as a declaration of need for fully qualified educators to fill vacant positions in the district.

The early retirement proposal, brought forward by Superintendent Maldonado, would offer staff — 411 eligible employees — the opportunity to retire early and earn up to 90 percent of their final pay, which would save the district at least $1.7 million.

“At this time of year, we would be getting resignations or announcements of retirements anyway,” Maldonado said, adding later that the district is “overstaffed” because of hires made last year. More teachers were hired to keep class sizes low, but many were paid for by one-time funds, which are expiring.

But boardmembers expressed unease at the proposal, especially considering the high turnover brought up repeatedly by teachers earlier that night. “I just don’t know that the timing is right, just given the sentiment that we just went through,” said Sims-Moten.

Ultimately, the board decided to take no action and discuss it at a later time. Later on in the meeting, they adopted a declaration of need for fully qualified educators — allowing emergency certifications and limited assignment permits for teachers to fill vacant positions outside of their particular subject areas, such as special education.

According to the declaration, 13 emergency certifications and 11 limited assignment permits are needed.

Where’s the Money?

Speakers at the November 14 board meeting also pointed fingers at the district’s spending, including the travel budget for administrators, and the amount spent on consultants and professional development for district leadership.

“It was recently revealed that the district travel and conference budget increased by an astounding $1 million,” said teacher Kim Baron, referencing the SBTA’s recent budget analysis.

“The money spent on consultants increased from $11 million to $16 million,” she continued. “Are you hiring the right people? It seems like the more people who work in admin, the more consultants you hire, and it doesn’t add up.”

District spending in the past few years includes a board-approved $10,805 on leadership training for Superintendent Maldonado in the 2022-23 school year. For several months in 2021, the board also contracted public relations firm Nichols Strategies for $50,000 to create strategic communications plans with the former Public Information Officer.

Over the past five years, the district’s total revenue has increased by about 40 percent, leading teachers to question why their salaries haven’t budged. They have consistently pointed out that, based on Santa Barbara’s high cost of living, they are considered low or very-low income, and make far less when compared to other districts.

After 27 years at La Colina Junior High School, teacher Rebecca Stillers is at the top of the pay scale, but she still can’t afford a house, and, at 59 years old, has to live with a roommate to afford rent in Santa Barbara.

However, Superintendent Maldonado and her cabinet make more than $1.1 million in salaries and benefits combined. Every member of her cabinet is new, except for one — Assistant Superintendent of Human Resources John Becchio. Almost every member of the district’s executive cabinet left in the three years after Maldonado was hired in 2020.

Madeline Bordofsky, a 5th-grade teacher at Harding University Partnership School, said at the board meeting that although the district expects educators to know every child by “name, face, and story,” they do not lead by example by getting to know their teachers.

“Unlike previous administrations who knew my name, my face, my school site, my grade level — I am certain that none of you could pick me out of a lineup,” Bordofsky said.

Maldonado’s former colleague from the Los Angeles Unified School District, Steve Venz, is the district’s new Chief Operating Officer, a position that Maldonado created and that, previously, never existed in the district. He earns $274,000 annually. The other members of her cabinet earn between $215,000 and $288,000 annually.

The district’s chief of communications, Ed Zuchelli, earns $181,000 annually. The district also recently hired an additional communications specialist for $71,000 annually.

Caballero and other teachers believe that the district may be “hoarding or hiding” extra funds that could go toward the classroom. “They look broke — they’re like, ‘We only have $40 to pay teachers,’ but it’s shady,” Caballero said.

Galindo said that the money spent on travel, conferences, and consultants is “worrisome.”

“Instead of putting that money toward classrooms, they’re hiring people to help them do their jobs,” he said. “They’re putting a lot more administrators in the office — by doing that, Hilda is distancing herself from the teachers and students she is supposed to understand and serve.”

Although he and his partner have been able to make it work in Santa Barbara in recent years, Galindo knows the struggle of living on a teacher’s salary in the district. “I have found myself homeless in the past,” he said. “It’s just indicative of how hard it is here.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.