Death of a Daily

The Rise and Self-Inflicted

Fall of the Santa Barbara News-Press

by Nick Welsh | August 17, 2023

There were warning signs even as the first celebratory champagne corks were exploding. I remember at the time — 23 years ago now — trying to contact Wendy P. McCaw for a comment and getting nowhere fast. She had just purchased the Santa Barbara News-Press, the county’s flagship daily newspaper then said to date back 132 years. Many in the community were giddy over the prospects her purchase seemed to promise.

What we knew of McCaw back then, admittedly, was next to nothing. She lived in Hope Ranch, was ungodly rich, loved animals, and spent lavishly to protect them. She was a libertarian, an environmentalist, a preservationist.

A rich, passionate eccentric who actually lived here.

What could be better?

At that time, the answer was nothing. We were far more concerned the paper would be sold to some over-leveraged, debt-riddled conglomerate that would usher in a slow-bleed regime of corporate cost-cutting and cookie-cutter journalism. After reading a paper owned and managed by the New York Times for 16 years, we’d grown spoiled. We wanted to stay that way.

I was quickly surprised to learn, however, there would be no interview with McCaw. Reporters were referred instead to a public relations outfit in Los Angeles called Sitrick and Associates. I can’t remember the details, but it was canned spam. The whole thing seemed weird.

At the time, I knew nothing about Sitrick. But his specialty, it turned out, was high-profile crisis management for high-octane celebrities who got in jams for punching their wives in public or even higher-octane oil companies — think Exxon during the Valdez oil spill — in toxic meltdown mode.

That should have been a tip-off.

The New York Times — which sold the paper to McCaw for something north of $110 million — would fare no better. Also denied access to her, the Times was forced to run a classic paparazzi drive-by photo of McCaw. The photograph was taken by Kevin McKiernan, a seasoned photojournalist and longtime Santa Barbaran; it would be the first photo ever taken of McCaw in Santa Barbara. McKiernan would wind up on McCaw’s Enemies List. She was reportedly furious with the Times for publishing her photo. Though the story has not been corroborated from News-Press sources at the time who would have been in a position to know, McKiernan heard from his Times editor that McCaw was so furious about being “hunted” that she almost nixed the deal. As a precaution, the editor said, he put McKiernan’s negatives in a safe.

Twenty-three years later, we still don’t know who Wendy P. McCaw really is, though, of course, stories abound.

People who actually know her either signed non-disclosure agreements or don’t want to risk litigation. But it’s a small town, and over the years her name has been routinely preceded by such adjectives as “reclusive,” “embattled,” “combative,” “litigious,” and “vindictive.” People familiar with McCaw from those days remain astonished and mystified how, aside from the obvious real estate values, such a ferociously private person would have — could have — signed up to become so public a figure.

No good could come from all this. It didn’t.

Spoiler alert: On July 21, Wendy P. McCaw officially deep-sixed the News-Press — her paper, our paper, the community’s paper. Turned off the lights and pulled the plug. We don’t know that the paper would have survived with someone else at the helm. We do know Wendy P. McCaw ran it into the ground. She was almost like the captain of the Valdez. But he at least had an excuse. He was drunk.

A Storke or a McCaw?

Courtesy

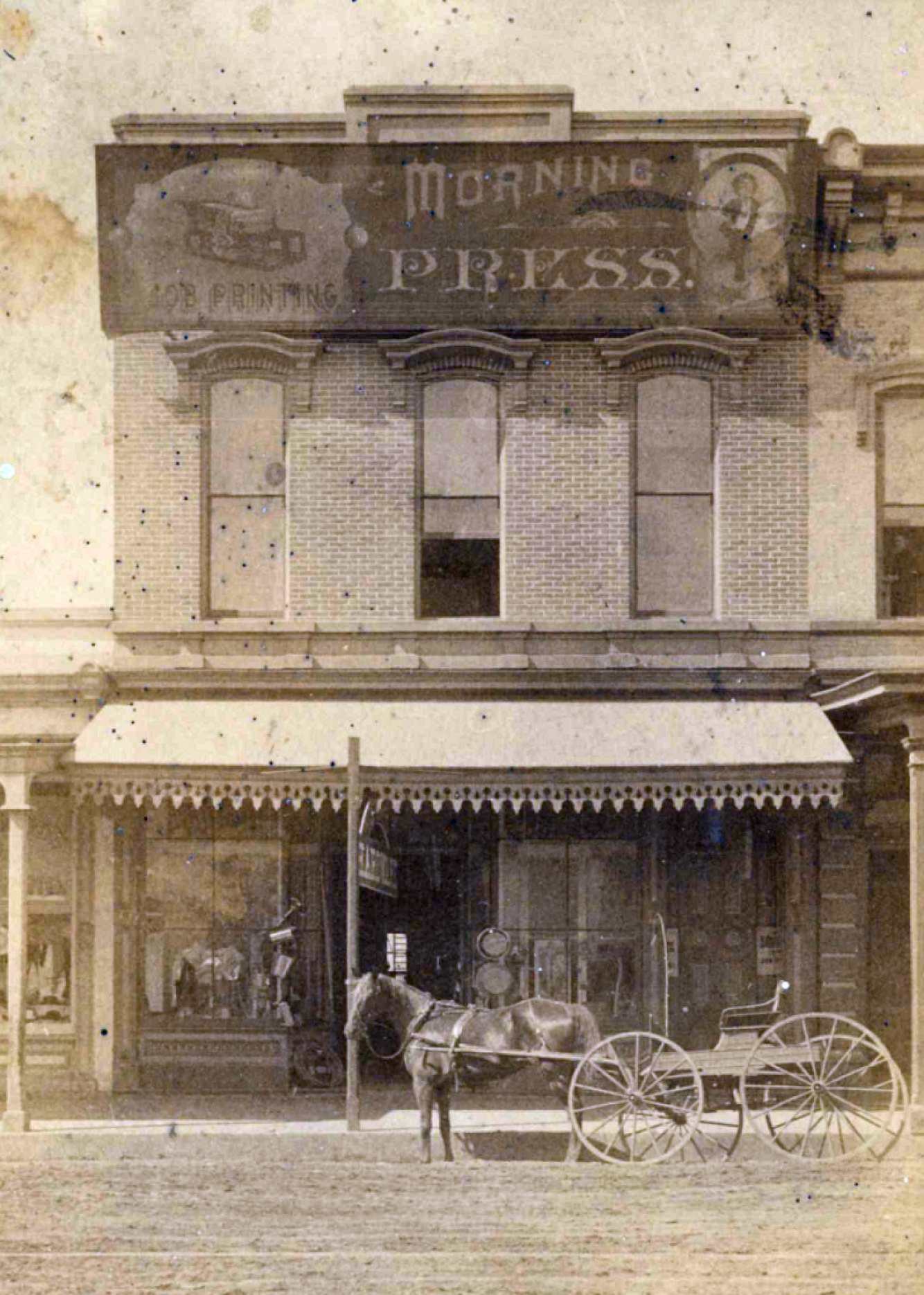

What McCaw didn’t seem to realize is that she had not bought just any daily; she had bought a daily paper in a town where people care passionately about every little thing. To an exceptional degree, the News-Press — under the direction of its original owner and founder, Thomas More Storke — had shaped the fundamental DNA of the South Coast after World War II almost as profoundly as the geologic forces that shaped the mountains and the sea. Time magazine would describe Storke — back in 1962 — as a “benevolent tyrant who has played king of Santa Barbara for 61 years.”

To run a newspaper, you have to be both “of” the community and “apart” from it. Admittedly, the market and media realities during Storke’s time — 1901 to 1964 — were very different than the ones that McCaw labored under. But Storke understood both parts of this equation. McCaw only got the second half: apart. From start to finish, the operating relationship between McCaw and the community was “talk to the hand.”

For the record, I’m not trying to make Storke a saint. He could be and was a bully. He tagged candidates he opposed as socialists when it suited his political agenda. In the late ’50s, he pulled strings to have a police chief axed, in part, because his officers hadn’t learned not to give “Mr. Santa Barbara” speeding tickets. The chief appealed. City cops packed the council chambers to protest Storke’s influence. The chief got his job back.

But if Storke saw himself as king, he looked out for the interests of his kingdom. For Storke, his kingdom was Santa Barbara and he wielded power from his castle tower in the News-Press building. Designed by noted architect George Washington Smith, it loomed over De la Guerra Plaza, Santa Barbara’s historical and political center of gravity.

Were it not for the political connections Storke cultivated over the years as owner, editor, and publisher of the News-Press, Santa Barbara State College would have never morphed into UCSB, today a major economic juggernaut for the community as well as a first-rate university. Lake Cachuma, which now supplies half of the South Coast’s water supply, would never have secured the necessary federal funding to get built. Without Storke and the News-Press, Santa Barbara would have no Earl Warren Showgrounds and no municipal golf course, though much of the heavy lifting was done by Storke’s son Charles, also a major player at the News-Press and in the community for many years.

And then there was Storke’s access to federal patronage to the tune of $32 million in federal relief funds that helped Santa Barbara survive the depths of the Great Depression. That’s far more than what other small communities our size were receiving.

If you take his autobiography at face value, that was Storke’s reward for his role in swinging the 1932 Democratic Convention in favor of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. If FDR hadn’t won that, there would be no New Deal. And it’s impossible to imagine how World War II would have played out without FDR in the White House.

Some have suggested Storke overstated his own importance in FDR’s political trajectory. And he probably did. But it’s incontrovertible that he was one of the key players working behind the scenes who successfully swung California’s delegation behind FDR at a heavily contested convention and when California was committed to a rival candidate. It was California’s vote, in fact, that put FDR over the top.

[Click to enlarge] Two-page SBNP article dated March 30, 1952 recounting the early history and mergers leading up to the News-Press. | Credit: Gledhill Library, Santa Barbara Historical Museum.

When a Tree Falls in the Forest

I mention this as someone who has spent his entire professional career competing against the News-Press. With that perspective, I have a cellular appreciation of the critical role daily papers can play in the ever-evolving ecology of news gathering and journalism. Like it or not, they’re the tallest tree in the forest. Cut down that tree, and the forest changes. We’re still trying to figure out what springs up in its absence and how sustainable that will be.

When McCaw put an end to the News-Press late this July — declaring Chapter 7 bankruptcy — it came as little surprise. It was like the death of a comatose relative long on life support. There’s relief. But there’s also mourning for what once was.

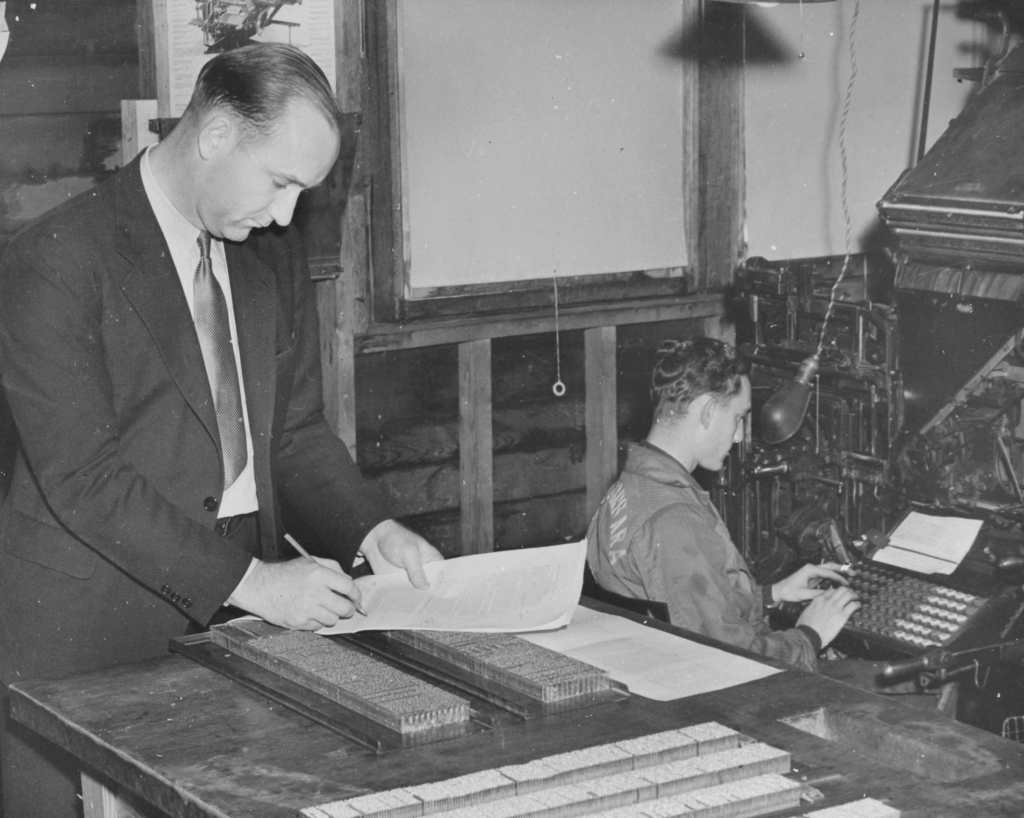

It might be hard to remember, but for the first five years under McCaw’s ownership, the News-Press was a humming machine, hitting consistently above its weight. McCaw lived up to her initial promise to stay out of the newsroom. But in 2006 — the year of the now infamous “meltdown” — many editors and reporters resigned over McCaw’s increasing intrusions into editorial decisions, including Editor Jerry Roberts. Since then, the paper festered and floundered. Except for the most cantankerous, conservative voices in Santa Barbara’s choir, the paper grew toxically alienated for the whole community.

Under McCaw, the News-Press would be the first newspaper in the country to endorse Donald Trump for president and one of a very small handful to do so twice. (Thomas Storke, a lifelong Democrat, was apoplectic over the defection of working-class Democrats to elect Ronald Reagan governor of California. Imagine how fast he must have spun in his grave when the News-Press endorsed Trump.)

While McCaw would later rail against the creeping totalitarianism she saw in the COVID-inspired health restrictions — masking, vaxxing, and limiting the number of supermarket shoppers at any one time — Storke and the News-Press would win a Pulitzer Prize in 1962 for their articles and editorials exposing public and clandestine recruiting efforts in Santa Barbara by the ultra-right-wing John Birch Society in 1961. The head of the Birchers wrote a 300-page tract accusing former president — and Allied Commander during World War II — Dwight D. Eisenhower of being a knowing and willing agent of Soviet subversion. The Birchers were especially drawn to Santa Barbara by the arrival in 1959 of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, which the Birchers regarded as a front for one-world communism. The Birchers especially hated Earl Warren, former governor of California and then Supreme Court Chief Justice most responsible for the unanimous ruling ordering school desegregation. Warren and Storke were close friends both personally and politically; it was Warren, as governor, whom Storke appealed to put the wheels in motion for the creation of UCSB. Warren frequently stayed with the Storkes during Fiesta. And Warren and Storke both would be hung in effigy in Santa Barbara during the heyday of the Bircher movement. While Storke would enjoy a bright but flickering moment of national prominence for his role attacking the Birchers, McCaw enjoys the distinction of being one of the few newspaper owners to have endorsed Donald Trump.

To run a newspaper, you have to be both “of ” the community and “apart” from it. The founder of the News-Press, T.M. Storke, understood both parts of this equation. McCaw only got the second half: apart. From start to finish, the operating relationship between McCaw and the community was “talk to the hand.”

When McCaw pulled the plug for good on July 21, 2023, there wasn’t a shred of a ghost left for the News-Press to give up. Earlier in the year, it stopped all home delivery. Then it retreated from its De la Guerra Plaza citadel to its printing-press plant located on a Goleta frontage road. There it hunkered down with its two remaining newsroom employees. Two employees! In 2006, when the meltdown erupted, 60 people worked in the newsroom.

Even so, the fact and finality of the paper’s demise sent shudders throughout the community. Most immediately, people wondered what would happen to the News-Press’s historic downtown building. What would happen to the paper’s vast treasure trove of records, photographs, and news clippings — truly a mother lode of institutional memory? And what about the printing presses themselves?

That will all be hashed out in bankruptcy court.

To Be Determined

The News-Press building, the printing-press plant, and McCaw’s downtown office building, it turns out, were transferred to different limited-liability corporations back in 2014. This distinct ownership structure will probably shield these properties from liquidation to satisfy the debts accrued by the News-Press’s parent company, Ampersand. Right now, McCaw is saying the News-Press owes $5.1 million in debt but only has $532 in the bank.

It will be up to the court-appointed trustee to determine whether there was anything actionable about the conveyance of these properties to other entities. The term “fraudulent conveyance” — a legal term of art — generally means that the transfer was conducted to shield an owner from the clutches of a likely creditor. Typically, evidence of such fraud is indirect at best; there are rarely smoking guns, experts say. Trustees reportedly look for what are called in the field “badges” of fraud.

The question in this case is whether there any such badges. Would the fact that McCaw came close to losing the News-Press building to a creditor — former editor Jerry Roberts — in 2012, shortly before the 2014 transfers occurred, be construed as such a badge? That will be up to the trustee to determine.

A key factor in all this will be the statute of limitations. Only in exceptional cases can fraudulent conveyance claims be brought after 10 years. One question the trustee must wrestle with is whether there are enough assets on the table to cover the costs of a likely courtroom showdown.

The answers to any of these questions are complicated and expensive. One thing we know for sure: While Wendy P. McCaw is hardly the only newspaper owner going out of business — roughly two per week were reportedly dying on the vine in the United States as of 2022 — she is the only newspaper owner who owns the building in which the bankruptcy proceedings will take place, in this case, the old I. Magnin building at State and Sola streets.

Without getting gloppy and sentimental, newspapers hold a unique place in the communities they serve. They’re privately run, profit-driven enterprises that also attempt to function as a public trust. In this regard, newspapers function like self-appointed grand jurors — charged with keeping elected officials accountable and the public informed.

McCaw, as has been reported extensively, left too many Santa Barbarans feeling that trust had been abused. Too often, newsroom workers charged, she used her news pages to protect friends and to punish her enemies. When reporters covered a land-use dispute in the summer of 2006 involving Rob Lowe and his Montecito neighbors, Lowe — then a friend of McCaw’s — protested that the story listed his name and the address of the property (even though he showed up in person to testify and the address was on all public documents). The writers and editors involved — and even one who was not — were reprimanded accordingly. When News-Press editorial page writer Travis Armstrong — whose daily diatribes were unusually harsh and personal in tone — was arrested for driving under the influence, pressure was brought to bear on News-Press editor Jerry Roberts not to run the story. Roberts ran it anyway. But when Armstrong was subsequently sentenced, that story never saw the light of day in the News-Press.

When McCaw took over, she hired consultants who warned the paper against breaching the lines between news and opinion. Not surprisingly, McCaw interpreted this to mean her reporters were injecting their own personal political agendas into their articles, not to do with the intrusion of McCaw’s own opinions into the news.

It was after McCaw gave Armstrong authority over the newsroom that Roberts, a well-liked and respected hot shot hired from the San Francisco Chronicle, resigned. As Armstrong escorted Roberts out of the building, newsroom workers heckled him, chanting, “Fuck you, Travis.” Many reporters were in tears.

Soon after that, newsroom workers voted 33-6 to affiliate with the Teamsters. When McCaw declined to recognize the union election results — objecting that they reflected coercion — the community responded favorably to the boycott drive launched by the union and began canceling their subscriptions. The workers’ slogan, “McCaw, Obey the Law,” appeared on placards posted all over town. McCaw responded by threatening legal action against the downtown businesses displaying those placards — many of whom had been loyal News-Press advertisers.

The News-Press found itself reduced to a state of siege. Surveillance cameras were installed in hallways. When five high-ranking News-Press managers attended a professional trade association meeting in Las Vegas, a private detective hired by McCaw followed them there. He made his presence conspicuously felt. When newsroom workers met at the Faulkner Gallery to discuss unionization, McCaw’s attorneys showed up uninvited. Employees were required to sign affidavits attesting they had not spoken to reporters from other news organizations about what was transpiring in the News-Press hallways. “This is war,” McCaw famously told one employee who made the mistake of attending a farewell party of a recently fired co-worker. “You’re either with us or against us.”

When Roberts resigned, he demanded six months’ pay, charging he was effectively forced out. McCaw countersued, demanding $25 million alleging breach of contract by Roberts and release of confidential information. After a protracted arbitration battle, the arbitrator would rule that neither side proved their case. Even so, Roberts would prevail; the arbitrator allowed him to collect legal fees — $915,000.

At the outset of this conflict, McCaw’s paper published an unsigned front-page Sunday morning article declaring that Roberts’s computer hard drive was being investigated for child pornography. Roberts was never contacted by the unnamed reporter for comment. The paper gave the computer to law enforcement authorities to investigate prior to publication, but the investigators concluded that it was impossible to determine who was responsible for the images. That’s because the computer had been used by at least three prior editors, it was not password-protected, and the images themselves were not time-stamped.

The arbitrator in the case, Deborah Rothman, described McCaw as a “complex, private, and principled” person. She also described McCaw as “brilliant.” But she rejected McCaw’s claim that Roberts was responsible for the News-Press’s loss of prestige and faulted McCaw for pursuing “a scorched-earth, take-no-prisoners, go-for-broke fashion … to punish Roberts for Ampersand’s public drubbing.” The arbitration dispute was limited to what transpired between Roberts and McCaw while Roberts was still employed. Because the child porn allegations were not made until after Roberts resigned, Rothman did not rule on them other than to suggest McCaw defied credibility when McCaw testified that she never used her paper to punish enemies.

[Click to enlarge] A large group of demonstrators descended on De La Guerra Plaza in 2015 to protest a front-page headline in the daily’s Saturday edition that labeled immigrants without U.S. citizenship as “illegals.” | Credit: Paul Wellman (file)

McCaw would irretrievably tarnish her own and the paper’s reputation with the publication of the story about Roberts’s article. Even for those indifferent to union struggles and journalism’s so-called wall between news and opinion, the News-Press’s reckless accusations and attempted character assassination proved a fatal last straw. The News-Press would never recover. From the outside looking in, it didn’t appear they ever tried.

McCaw’s stated beef against Roberts was that he almost single-handedly tarnished the reputation of her paper. The facts would suggest that if McCaw has a defamation lawsuit to file, it would be against herself.

Astonishingly, Roberts would find himself the only person ever tarred with the kiddie-porn brush to come out with his reputation not only intact, but enhanced. In direct response to his last days at the News-Press, Roberts received ethics awards from three prestigious journalistic organizations.

Now What?

The $64 million question, of course, is: what now?

When Dave Davis — the City of Santa Barbara’s former Community Development Director and currently visionary-in-chief in charge of the latest State Street master planning endeavor — moved to town in 1978, the first book he read was the News-Press publication 100 Years of Headlines. “Three themes kept coming up over and over and over again,” he recalled. “There were affordable housing, water, and transportation. For me — as a new planner who had just moved to town — that long-term institutional memory the News-Press offered was unique and invaluable. And it still is.” More than that, Davis added, the daily paper is — was — uniquely equipped to function as the town center. “It was the platform where we all could get our shared facts. We could argue about what those facts meant. But it gave us the shared platform for having those discussions.”

What happens now? I don’t pretend to know. But I do remember sitting on a panel discussion on the future of journalism back in 2006 as the News-Press meltdown achieved critical mass. My answer then was simple: We need more bodies. More reporters.

My answer today is exactly the same.

More bodies.

More reporters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.