800,000 Building Permits but Not Enough Homes in California

Childcare, Workforce Housing for Employees Proposed by Santa Barbara County Builder at Goleta and Carpinteria Projects

About 800,000 building permits ago, California was facing a housing shortage of roughly three million homes, and cities are doing some crazy things to find the real estate to satisfy the state’s new housing quotas. Up in the Bay Area, Sausalito attempted to claim 28 low-income sites on an underwater swath of eelgrass, and Orinda tried to slip in some odd parcels — one of them banana-shaped and another one-foot wide.

In Orange County, the City of Huntington Beach is simply fed up. Its city council doubled down on its refusal last month to comply with granny-flat rules, proposing a city law on Tuesday to exempt itself from the Builder’s Remedy language in the Housing Accountability Act. State Attorney General Rob Bonta held a press conference on Thursday, backed by Governor Gavin Newsom, announcing his office was filing a lawsuit to compel Huntington Beach to comply with the state rules.

The cause of these desperate actions can be observed in the new Bailard Avenue development proposed just outside the City of Carpinteria’s borders. The builder, Red Tail Acquisitions of Irvine, filed its application under Senate Bill 330 — which limits public hearings to five — and the Builder’s Remedy, which precludes local zoning and land-use rules. “Local” in this case is Santa Barbara County, and the reason Red Tail may use the remedy is because the county missed the February deadline to file its Housing Element.

The community opposition to the project is already fierce. At a Planning Commission hearing on Tuesday, Carpinteria Councilmember Wade Nomura, formerly a proponent, spoke against the project’s density — 41 lower-income and 132 market-rate workforce housing on 6.5 acres — and lack of city input. As well, the Save Bailard Farm movement brandished a petition with 2,500 signatures in opposition, as an organic farm operates on the land, which is zoned residential.

But what’s extraordinary about the Carpinteria project is the developer’s take on the concept of “workforce housing.” Red Tail intends to base its market-rate rents on Oxnard/Ventura prices — lower than Santa Barbara’s, and more than 11,000 people commute from Ventura County — and the developer also intends to seek out employers who want to house their employees closer to their workplaces.

A Developer with a Heart?

Red Tail has a second project— Heritage Ridge in Goleta — in concert with the Housing Authority of Santa Barbara County (HASBARCO), whose John Polanskey divulged the plans for Carpinteria’s Bailard project.

“We are very careful about who we pick to work with,” said Polanskey, whose nonprofit has created 5,466 lower-income homes during its 81 years, “and Red Tail have been really good partners.” The real estate company was one of the developers on the Villages at Los Carneros project, at which People’s Self-Help Housing built and manages 70 units of affordable apartments. Across the street is Heritage Ridge, 228 market-rate homes and 102 apartments for very low- and low-income seniors and families — to be purchased, built, and managed by HASBARCO — which the Goleta City Council approved on Tuesday night.

Polanskey viewed the mix as uniquely beneficial; families can work up to the market-rate homes at the complex and stay in the same school district. And at Rona Barrett’s Golden Inn and Village in the Santa Ynez Valley, he recalled that they built a bridge over a creek because of the relationships that had developed between the seniors and the children living next door.

At Heritage Ridge, Red Tail has been accommodating to a striking degree. On Tuesday, Councilmember James Kyriaco noted that low-income housing at the project started at zero percent — back in 2014 — and rose to 31 percent as approved. Between that and the conversion of the Super 8 motel at Fairview and Hollister avenues into permanent housing for homeless people, Goleta could satisfy nearly 20 percent of its state-mandated lower-income housing responsibilities. Kyriaco also applauded the $7 million the developer forfeited in discounting the land to HASBARCO on a project that is estimated to cost $70 million to build. To help fund the affordable portion, the developer is paying more than $3 million in fees, and the city is adding a $1 million forgivable loan.

Over the years, the Heritage Ridge project changed through myriad meetings — a half dozen with city design and planning boards, an uncounted number with Chumash groups and the Environmental Defense Center. All the changes added to costs, which Red Tail absorbed. The exteriors went from an angular “deco” style to the warmer Craftsman design. A two-acre public park is at its center, replete with educational Chumash signs and play equipment. The developers actually moved a building to accommodate the 100-foot creek setback, losing about 30 parking spaces in the process.

Councilmember Luz Reyes-Martín observed that Heritage Ridge was an achievement of compromise: “In many ways, this is the model for how to do this. Many people get together, hash things out, and have the open minds to get to ‘yes.'”

The Towbes Connection

Red Tail’s representatives declined to comment about the project, but one reason they were so willing to bend could be due to Michael Towbes. He bought the property a half century ago, in the 1980s, during his long lifetime of work in real estate, development, and banking. When he died in 2017, his estate was complex. Completing this project — which is the third of Towbes’s Willow Springs housing developments — wasn’t practical, said Robert Skinner, who is his nephew and CEO of the Towbes Foundation. Instead, they sold it to one of the principals at Red Tail Acquisitions, who has a house in Montecito and supports some of the myriad nonprofits the legendary philanthropist was known to endow. Skinner explained the estate sold the land at a “significant reduction,” recognizing Goleta’s position in needing to satisfy the Housing Element’s lower-income housing requirements.

“It was that ‘contribution’ by the Towbes estate that ‘bridge’ the project economics to make the affordable housing possible,” Skinner said. “The affordable units represent approximate 31 percent of the total units now approved, which I believe is significantly in excess of the affordability requirements under the current Housing Element.”

Red Tail had indeed taken the Goleta council’s temperature. Included in their proposal are ways to add home-based childcare at the individual apartments, goals dear to the hearts of Kyriaco and Reyes-Martín.

The folks in HASBARCO’s housing income level would earn 50-80 percent of the area median income, or between $62,450 and $100,050 for a family of four and $43,750 and $70,050 for a single individual. And Heritage Ridge hits what Polanskey calls the “sweet spot” of 40-60 units that make tax credits and other funding feasible. The seniors’ portion is about 41 units, and about 63 non-age-restricted family homes would be built. Two apartments are set aside for managers.

Commuting, Housing, and Building

Other numbers to consider are the 20,000 commuters into Santa Barbara County — from the north and the south — and the roughly 2,000 homeless people who are living in doorways, tents, shelters, and vehicles. How their lives would change if they were all housed locally. And the very same situation exists across the state.

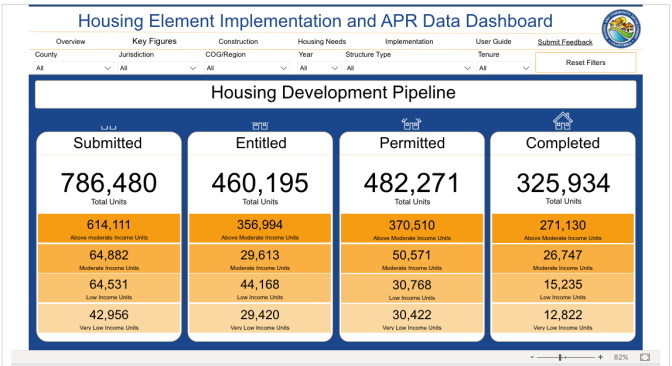

California’s cities and counties issued 800,000 building permits over the past eight years. That number was supposed to be 1.1 million under the state’s mandates. When looked at by income category, permits were issued for only 18 percent of the very low-income target number of 277,269. Above-moderate-income units, on the other hand, had a target of 485,664 that was exceeded at 138 percent.

What the state has noticed is that permit applications submitted didn’t translate to housing getting built. Since 2018, planning departments have been required to describe units built — a five-year span compared to the eight years of permit information available. But the discrepancies seem large, nonetheless: Of the permits for 786,000 units submitted in 2018-2022, 325,000 were completed. Very low-income homes built numbered 12,000 compared to 42,000 submitted.

In Santa Barbara County, permits for 4,647 units were submitted during the five-year period; of those, 4,046 were built. Among very low-income units, 361 were submitted and 191 were built. The shortfall continued for low-income and moderate-income units.

Statewide, the response by the Housing and Community Development agency has been to crack down on what it will allow in Housing Elements for the next cycle — the 6th Cycle — wanting more certainty in the form of plans or developer interest. Housing advocates examine city and county documents, writing pointed social media posts on the proposals that beggar belief. Planning departments have hired the handful of available consultants, who’ve hunted for clues on what will pass muster in the successful housing elements submitted.

The Parcel Quandary

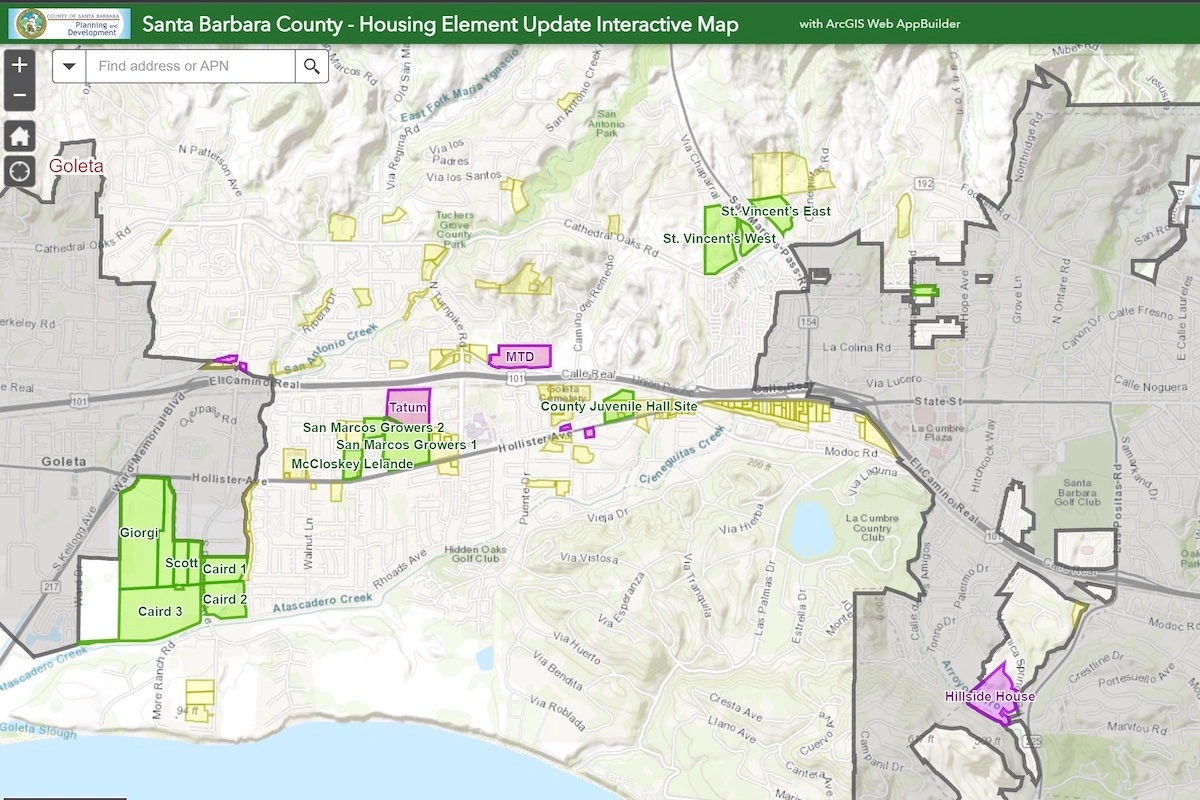

The statewide housing allocations more than doubled for this cycle — from 1.1 million in the 5th to 2.5 million in the 6th. In the county, the overall allocation climbed from 11,030 to 24,856. For South County unincorporated lands, it went from 501 to 4,142. North County’s rose from 160 to 1,522 in unincorporated areas. Like Carpinteria, the City of Goleta finds itself between a rock and the County of Santa Barbara over housing on what’s arguably farmland, but also at a golf course right at the city’s borders.

Each set of parcels check many of the state Housing Element boxes — they have willing landowners or developers, permits and plans are in the works, and sewer, water, and other utilities either exist or are at neighboring parcels.

But Goleta councilmembers Kyriaco and Reyes-Martín argued in an editorial that 75 percent of the county’s 6th Cycle housing is proposed near Goleta. As placed on South Patterson farmland along the Old Town corridor, it would affect the nearby disadvantaged community, a form of environmental injustice as wealthy areas like Montecito, Summerland, and Hope Ranch are excluded from the county’s plan.

Goleta has been actively looking at county parcels for alternatives, and the South Coast’s county supervisors have been, too. Supervisor Das Williams offered that Rick Caruso’s Miramar was willing to plan for some employee housing in Montecito, and Supervisor Laura Capps found Magnolia Shopping Center could be added as a mixed-use site in Noleta.

Supervisor Joan Hartmann’s 3rd District includes about two-thirds of Goleta, and she said she and her staff were beating the bushes to locate suitable parcels in South County. “We are going to focus on underdeveloped areas as opposed to going into agricultural lands,” Hartmann said. “I have a long history with this, and my values are to protect agricultural and open lands,” she said. “I haven’t abandoned that in this Housing Element update.”

Sewers and Traffic Gotta Flow

The cities and counties that succeed in attracting developers to build lower-income affordable housing — through grants, incentives, and housing-friendly policies — will face other issues, such as water, sewer, and traffic costs.

The Bailard project near Carpinteria and the South Patterson farmlands just outside Goleta already have water entitlements. In fact, most crops use more water than people would on the same acreage. The general manager for the Carpinteria Valley Water District, Bob McDonald, indicated they had more than enough supply as projected out to 2045. This includes the addition of the Bailard project, the City of Carpinteria’s own 901-unit Housing Element requirement, and another 40 units possible at the Polo Fields.

In Goleta, the water district has stated that if its groundwater level increases to the point it can lift the current moratorium on new hookups, it could add about 1,000 new residences to its customer base. The water district serves the city — which must add 1,838 units in the 6th Cycle — and would serve the 2,734 units proposed on the farm fields at South Patterson Avenue and the 1,536 units at Glen Annie Golf Club.

What about traffic impacts and sewer demands? residents have asked. It’s all gotta flow, after all. Both will be the basis for heated arguments in the coming years, but Gregg Hart, who’s been in the Assembly for a couple of months but in county politics and policies for decades, has already immersed himself in the state’s enormous budget for the coming year and its effects on housing.

Hart noted that in the past 30 to 40 years, even though the South County population doubled, water consumption was actually cut in half through conservation and water-saving appliances. Regarding the sewer and traffic issues that result from the housing mandates, Hart said, “Last year, there was a massive budget allocation — $7.2 billion — to support housing and homeless services. Out of that, $425 million is set aside for infill-development infrastructure grants as state support for local governments.”

What About Hope Ranch and Montecito?

Hart’s old supervisorial district, the 2nd, includes the 4000-4400 block of State Street, a county area roughly between a Hyatt motel and Eller’s Donuts, and zoned for mixed use — or both commercial and residential. “Our staff looked at that area,” said Lisa Plowman, head of county planning. “It’s been zoned that way for eight years, but there’s no data to support that the area will produce low- or very low-income housing, which is our biggest need.”

Plowman acknowledged the St. Vincent’s charitable organization planned a mixture of supportive housing and transitional housing there, saying the county would include the permanent units. The planners would be updating the map as they got ready to submit the Housing Element, she said, likely in late March.

Even if all the parcels along those blocks — about two dozen of roughly an acre or less — were redeveloped for mixed-use commercial and homes, would that be enough to offset the farmlands near Goleta? Housing guru Frank Thompson shook his head regretfully. “Even with Buffy Wicks” — an Assembly bill that increases density for mixed-use projects that include low-income homes — “allowing 60 or 80 units per acre, and it’s right on major bus lines, it still might not be enough of an incentive to attract a developer. If the county excludes Noleta, they can’t get there.”

Noleta, of course, includes Hope Ranch, nearly as expensive a neighborhood as Montecito but home to no royals as high up the food chain as the Windsors. Thompson thought low-income housing wasn’t too likely. “Even if you found a half-acre parcel in Montecito, how is it zoned? Ten units? Who wants a five-year riot to get 10 units?” he noted of the protracted and well-financed opposition that would result.

He then wondered aloud about the parking lot at the Biltmore — virtually abandoned since the pandemic — which is on two acres set aside for employees and guests: “That’s not included on the county’s list.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.