Getting the Run of the Joint:

Joan Tanner’s Field Day

at S.B. Museum of Art

Artist Brings Distinctive Work to McCormick Gallery

By Josef Woodard | Photos by Ingrid Bostrom | February 23, 2023

Something is blissfully amiss at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Walking into the SBMA at the moment, a wonder-filled and slightly disorienting view greets the visitor. The wall facing the open-feeling Ludington Court area up front, leading us into the museum’s central McCormick Gallery, has been benevolently invaded by what resembles a massive, chaotic bouquet of bulging netting and other common materials. Museological politeness and decorum take a holiday.

Proceeding into the large gallery space, we see that this colorful mass, called “Mire,” is actually connected by a long, umbilicus-like tube to another exuberant structure, folded into and resonating the slash conversing with a teeming garden of fantastical sculptural delights.

It’s official: the McCormick has been Tanner-ized.

This is artist Joan Tanner’s time to shine and stretch in the primary hometown venue, where she had her first show back in 1967. Tanner, widely respected and still wildly inventive and active at age 87, has produced a viscerally and conceptually captivating exhibition, Out of Joint, a validating powerhouse of a show from one of the finest and most creatively vibrant Santa Barbara–based artists.

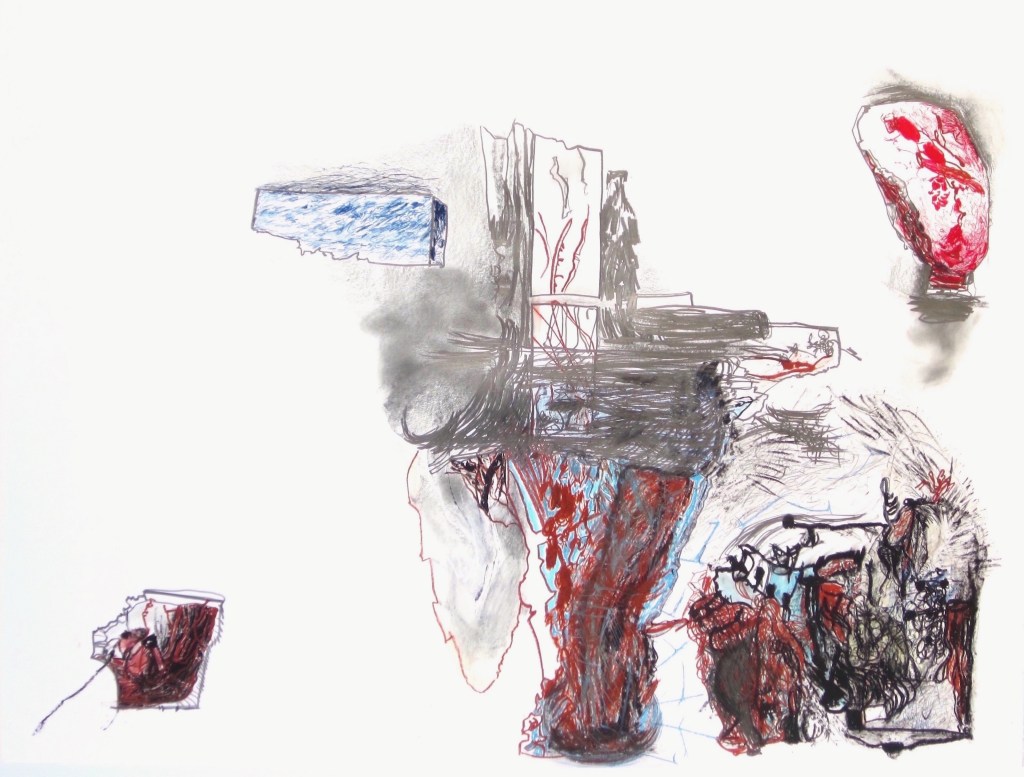

Composed of drawings and expansive, raw-material-grounded sculptural creations — many of which are site-specific — the exhibition, curated by SBMA’s relatively new curator of contemporary art, James Glisson, embodies that signature Tanner trick of being at once splashy and cerebral.

As she walks me through the exhibit at SBMA, Tanner mentions that “a funny thing happened recently, when [photographer] Richard Ross sent me this obscure text — ‘It was nice to see you at the Hammer [Museum in Westwood].’ And I thought, ‘What the hell?’ The next thing that he sent was a photograph. They borrowed a very early piece of mine that I haven’t seen for ages. So of course I had to go down and look at it. Yeah. And then you kind of go in like, ‘Oh God, this is so embarrassing.’ But I want to see what it looks like.

“There are little pieces of your history scattered. Isn’t that nice?” She pauses and gives me an impish sidelong glance, confiding, “You know, I’m old — 87.”

Under normal circumstances, a seasoned artist might be given a retrospective overview of a show. But, as Tanner is still very active and now-and-forward-thinking, this exhibition extends back only a decade. It was in 2013, in fact, that she had a memorable drawing show in the wonderful and missed Jane Deering Gallery, called in direct dialogue. Locally, she also had an important show in 2000 at Contemporary Arts Forum (now the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara), an organization she was vital in making manifest in the late ’70s and ’80s.

Just since her Deering Gallery show, her reach beyond Santa Barbara has extended to shows in Seattle, Philadelphia, the University of Louisville, and, in 2021, the exhibition Flow at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center. Past shows of note include On Tenderhooks, a fantastical

sculptural constellation at the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, in 2006. She’s been around, and the story continues.

Tanner takes me on a personal tour of her exhibition, talking about the work, its possible meanings, and cross-references — while still acknowledging the malleability of meaning in her art. Along the way, she also addresses details of her life as an artist, a journey of six decades so far.

In the museum lobby downstairs, an artist comes up to her and expresses his admiration, holding up his phone to show a new piece inspired by her work. “Okay,” she responds. “Well, have at it.” She then adds, with a conspiratorial tone, “Just don’t trespass too close.”

We stop to look at a quartet of large drawings, with vague landscape, water, and archeological suggestions, including “End of Water” and drawings in her Staunch series. She pointed out that the drawings were “the first work that the new kid James Glisson saw in my studio. He came from the Huntington Museum [in Pasadena]. I was kind of taken aback, but he just dove right in. But I didn’t know then that it would lead to the invitation to have a show. So it took a new person in town, from a traditional old museum. We had a lot of visits.”

End of Water #2 and #4 | Credit: Courtesy SBMA

Tanner’s wide purview and innate curiosity as an artist might be traceable to her roots as an artist, hailing from the Midwest but drawn to Santa Barbara decades ago.

As she explains, “I went to the University of Wisconsin [in Madison], and you could literally take anthropology or anatomy. It was not the tight program of other colleges. So I was an art major, but I took a tremendous amount of art history. And I even took art history and the history of architecture, in which the teacher guy talked about the greatest buildings never built.”

She continued, “When I think ‘How does that stick in my head?’ it must have been the beginning of structural relationships, some of which are loose and are cliffhangers, [suggesting] the tension and contemporary architecture.” Frank Lloyd Wright was a visitor to the University.

“I never felt apologetic that I grew up in Indiana. I’m from a place where Purdue University is [in Lafayette, Indiana], and maybe growing up in that kind of aura of engineering school had an impact on me. But I was terrible with fractions,” she laughs.

“I can’t possibly conjure up how I was as a kid. But I have a feeling that my mother just gave up and said, ‘Do whatever you wanna do, kid,’” she says with a laugh. “I never felt as a young woman that anybody ever said, ‘Joan, you can’t be an artist.’ My dad was an eye surgeon, and he was sort of like, ‘What do you wanna do? Oh, you gonna do this? That’s good.’

“Post-war, a lot of people that were on the campus were vets. It was a wildly liberal place. There was a communist organization, but I was sort of shy to say, ‘I really don’t know what that’s about, but I’d love to join you.’ So this,” she says, gesturing to the art in the room, “in an incongruous way, has to do with that. I could use this and I could adapt it to anything.”

Painting was Tanner’s original medium, but her main interests now are drawings — which often ambiguously suggest architecture, archeology, or antique topography — and her ever-evolving ideas on the subject of contemporary sculpture and installation art. (In a fortuitous cross-exhibition resonance, SBMA is also currently hosting a show in the upstairs contemporary gallery of work by Ed and Nancy Kienholz, whose use of “generic” materials had an influence on Tanner.)

As Tanner says of her shift from painting to her action-packed sculpture, “[With painting,] I was attempting to kind of leap off the canvas without overworking it. I was always very conscious of … trying to create space that didn’t exist.”

Now, she defines space and rivets our attention via sculptural means. Another dazzling new piece in Out of Joint is the ensemble of large, colored, and bent plywood forms making up “Shaped Plywood,” which might trigger associations with Alexander Calder or Jean Arp’s formal playground.

Steering mostly clear of traditional tools, processes, and materials of the sculptural practice, Tanner happily finds her art essentials in unexpected places, including plywood, netting, tubing, and her new discovery: the flexible metal known as Flex-C Trac. Is she interested in finding new materials as part of her artistic venture, as well as the sustainability concept of repurposing?

“Yes, [I] repurpose, but also scavenge and, I dunno, take advantage of,” she laughs.

Aside from the epic “Mire” and “Yellow Mesh” in the show, a strong example of Tanner’s distinctive way with sculpture is the newest addition to her Contingent series, which could be viewed as a loosely figurative variation, writhing in its form and suspended off the floor to levitational effect.

“This is the last piece that we made in the studio,” Tanner says, “so it was hot off the press. The Flex-C Trac is an articulated steel plate that is used to make arches. I wanted something that I could manipulate somewhat easily, that wasn’t so incredibly heavy. I was able to make these more voluptuous curved forms. Then I began to bundle things with this much bigger gauge of plastic fencing.” Further expressing her excitement about Flex-C Trac, Tanner appreciates “being able to have something that I can manipulate because it’s thin or we can attach it or I can penetrate it without too much effort. And then bandage it in this piece and wrap coils around to basically make a semi-spinal.”

Tanner isn’t one to mince words about responses to her work, as well as other topics. “What irritates me is a lot of questions from people who don’t get it,” she says. “I don’t enjoy the discourse of ‘Oh, those materials — how did you come upon that?’

“It falls into the category of process art,” she says, referring to the ’60s movement emphasizing the process and the action involved in art’s creation over the end result or specifics of form or materials. She adds, “but process art really is also a boring term, because you almost have to go back to Arte Povera [an Italian art movement in the ’60s meaning ‘poor art,’ relying on raw, humble, and quotidian materials], of which a lot of people are clueless.

“It’s embarrassing to think that if it’s to compare myself with some major, major international person. I’m perfectly content to acknowledge what I made something out of. But in the order of things, I don’t think it’s interesting how you mull that material over another, to talk about, ‘Oh, she just went out to Home Depot, just brought a lot of stuff.’”

In general, Tanner’s approach to creating her art, especially in the sculptural arena, is subject to change and following instincts. She asserts, “I really am interested in structure and in something that I’d call tentative, or my favorite new word: indeterminate. That gives me a very slippery slide. I can go all over the place.”

Apropos of Tanner’s natural attraction to exploration and spontaneous creative combustion, she mentions, “My grandson is a jazz pianist that’s finishing up at the New School in New York. He calls me late at night and says ‘Hey, I want you to listen to this.’ I love that improvisation.”

Real worldly matters are not lost on her, as when she says of Contingent, “Doesn’t it remind you of a Lionel train?” Elsewhere, she points to specific sections of her congregant sculptures and notes their resemblance to a pancreas, or a heart. “I come from so much medical background,” she relates. “I grew up at a dinner table where my dad would say things like, ‘God, you know, I just did the most magnificent cataract surgery,’ and then proceed to tell you why the incision was so right,” she laughs. “I don’t ever remember being squeamish or whatever.”

Clockwise: donottellmewhereibelong #33, #20, #13 | Credit: Courtesy SBMA

In a smaller gallery off to the side of the McCormick is a group of Tanner’s drawings — many in the sizable series called donottellmewhereibelong — along with smaller, more ironic sculptures in a post–pop art style.

At the end of our interview/tour, we sit in the Ludington Court, in the shadow of the signature massive nude male figure of the Lansdowne Hermes. I asked Tanner about the origin and intent of the compound title donottellmewhereibelong. “I really wasn’t gonna name that series,” she comments. “I was reading a lot about the displacement of people in New York that were poor and couldn’t stay in a building any longer. It was not so much about the giant influx of immigration, because it wasn’t happening quite as heavily as it is now. I remember reading a very long piece, a three- or four-part series about this woman that lived in New York City and slept on the sidewalk. Particularly in the winter, some of the high-end proprietors wanted to help her and bring food, but also wanted her to not be there.

“She was cogent and she would get on a bus or a subway. It turns out she was in the class of African that were given scholarships as they were a cluster. She was in possession of her own self that she was not gonna try to be placed.

“And so this phrase [“donottell

mewhereibelong”] started coming, and then I would say to someone I was talking to, ‘Can I run an idea through you?’ I realized that just displacement is obviously a massive fear. I can only say that it just generated a lot of desire to be very specific and drawing in a way that I borrowed from maps, from diagrams, science textbooks and technique.”

In a sense, the phrase might also be a reference to Tanner’s individuality as an artist, one who doesn’t “belong” in a tidily defined “ism” or school in the known art world.

“Well,” she grins, “I think you could do something with that, maybe. I haven’t really been a rebellious mind. It isn’t a call to action. What bothers me is when people make fatuous comments, when they’re off on the total wrong track.”

Out of Joint is a major undertaking for Tanner, particularly in terms of shows landing in her hometown. It illustrates many of the aspects of her aesthetic inner life, expressed with a sophisticated panache, in a living-large fashion. Still, despite her age, she’s not ready to lapse into the realm of retirement and retrospective thinking. “I don’t think this is conclusive,” she says of the show. “That’s the other thing that’s really important to me.

“I almost wanna call it a segue to something that might still happen. I have been particularly devoted to labor, and the making because it’s — I don’t know where I’m going. Isn’t it my job to finish, in a sense?”

Out of Joint: Joan Tanner is on view at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (1130 State St.) through May 14. See sbma.net.

You must be logged in to post a comment.