“A little too abstract, a little too wise, it is time for us to kiss the Earth again…”

—Robinson Jeffers, Return

Land of the Unseen

We board the National Geographic Resolution, newly christened in 2021 and captained by Martin Graser. Peter Wilson is the Expedition leader. I join Macduff, who is the National Geographic photographer on this eight-day expedition into the fjords, archipelagos, and islands of Patagonia.

This is a land of the Unseen — so much of it lies beneath the surface. From the tip of an iceberg to the craggy top of a fjord, their underwater presence expands far and wide. It is not an easy place to get to, the ends of the Earth. Patagonia is an area shared by Chile and Argentina, a place where boundaries matter greatly to the human inhabitants, not so much the rest of biological life.

Patagonia is a land layered in legend and redolent with mystery. Its very name has become a metaphor for the wild and extreme. In 1520, Ferdinand Magellan and his crew brought back tales of a near-mythic race of naked humans. They imagined these creatures to personify the monster in Primaleon, a popular chivalric potboiler of the day, in which a knight rescues a princess from the grips of a huge, blood-smeared, meat-eating colossus called Pathagon. Thus, literature fueled Magellan’s imagination to name the region. It was just the first of many exaggerations and romantic notions associated with the area that continues to be known as Patagonia.

Asada at an estancia

After landing and overnighting in Santiago, Chile, we fly a charter to Punta Arenas, the southernmost airport on the continent. Then a three-hour bus ride to reach our ship. Midway, we enjoy a visit to Estancia Río Penitentes.

It is windy, chilly, with snow flurries, but upon entering the aroma and warmth of the dining hall handsome men sporting the traditional boina — the traditional caps worn by gauchos and baqueanos — welcome and invite us to enjoy a chilled pisco sour. An entire lamb, flayed and fastened to an iron rack was roasting on a hot fire. I now know the origin of ‘rack of lamb.’ Long tables accommodate us all for an asada, a sumptuous feast of grilled lamb, roast potatoes, salads, and fine Chilean red wine.

The Morrison family from Scotland settled here in 1891 and the ranch remains in the care of their descendants, brothers Alexander and Cristian Dick, who shepherd flocks of sheep and a herd of 75 llama. Afterwards, fully sated, we make our way to Puerto Natales to meet our ship docked in Last Hope Sound. After greeting the captain, expedition leader and staff, we settle into our cabin. That night I had the first sound and delicious sleep in days.

To the Fjords

Eleven smart and friendly staff safely usher us in and out of Zodiacs for daily excursions, all the while imparting their deeply informed understanding of glaciology, geology, ornithology, indigenous culture, marine biology, undersea wonders, and even a bit of Medieval English literature, and Flamenco guitar. They are our enhanced eyes as we cruise through narrow canales or arrive on a caleta to explore inland. The guides work tirelessly to create an experience that enriches our appreciation, preparing recaps that we enjoy every evening, while sipping a drink served to us along with hors d’oeuvres. Captain Martin and his team, Peter and Macduff, and naturalists Jeff, Dan, Kevin, Shayne, Jackie, Katie, Jesse, Andreas, Rob, and Cammi, and a well-trained crew are the skilled underpinnings that create such a smoothly run operation.

In the morning we embark on our journey through the maze of fjords via the White Narrows. The captain has calculated to arrive precisely at the few minutes of slack tide.

The long fingers of the fiords cut into the land are the handprints of glaciers that carved and shaped this landscape. We head to Canal de las Montañas, a gouge scored fathoms deep and straight as a rule. Between saw-toothed ridges glaciers nose into the channel. Remnants of a late winter storm dust the shoulders of the fjord with snow. Our first landing is on Kawéskar National Reserve named for the indigenous peoples of the area. The ship nearly kisses the coast as Zodiacs ferry the guests ashore. A lush trail through shiny pig vine, juncus and Magellanic fuchsia leads to the terminus of the retreating Bernal Glacier. We stand on the glacial moraine, a fine-grained loess, that the glacier’s convex nose has ground like a sanding belt, the moraine archiving everything in its hold.

The next morning some guests kayak, some pile into a Zodiac to explore the coves, waters, and islets as small as scones around Isla Capitan Aracena in Estero Staples. Two Chilean pilots on board our ship commented that it might as well be considered uncharted, unnamed territory as no other ship our size had been here before. We’re anxious to see what we can see. The guides call out sitings to one another. “Steamer ducks, an entire raft of them!” exclaims Shayne. The flightless steamers indeed float in unison as one raft, and then in a blink, they furiously thrash their tiny but powerful wings like paddle wheelers and take off helter- skelter. I can’t help but giggle. They are adorable. Close to the cove two sleek Chungongo otters weave in and out of the coppery kelp, then scramble up into the densely foliated granitic islands towards their den. They are the smallest marine mammal on earth, with a hummingbird’s metabolism they must feed constantly. Project Noah has listed them as Endangered due to habitat loss and being illegally hunted for their luxurious pelts. On land, tangled dense beech with slender grey limbs twist like ecstatic twerking dancers. At the tip of an islet a regal deep green native cedar tree rises like a beacon amid the slabs of granite embellished in a tapestry of lime green, saffron, white, russet, and black lichen, and moss.

The Albatross that awaits you at the end of the world

Captain Martin Graser loves this ship. Before dinner he speaks for 90 minutes, and his enthusiasm is infectious. Built in Norway, the ULSTEN ice class Polar 5 vessel has an X double hull ice bow with Azipod electric propulsion and sideways thrusters that allow zero-speed stability and incredible maneuverability, replacing the need for an anchor, leaving the sensitive sea bottom undisturbed. Martin made essential modifications to the basic design, such as a V-shaped bridge as if it were a piano where he would know precisely where to place his fingers. An OLEX sounding system conceived in part by Norwegian fishermen and Lindblad becomes a data sharing system for charting uncharted, unexplored waters. There is far more, but all I know is that this energy efficient ship seems to float above the water, and I once again marvel how beneath the surface of our voyage, this masterfully designed creation exponentially enhances both our safety and our experience. Dinner cuts short as we head on deck to exalt in the embrace of a full spectrum double rainbow across the bow, before turning in.

Cape Horn marks the northern reach of the Drake Passage. It is where the Pacific, Atlantic and Southern seas converge, unimpeded by any landmass. It is known as a mariner’s nightmare, where wicked westerly winds combined with abrupt rises of the ocean floor create massive waves to crash on the jagged shoals. Before the opening in 1914 of the Panama Canal, when it was even busier, hundreds of ships, and over 10,000 seamen lost their lives trying to round the Horn. But when we arrive it is miraculously windless and downright summery. The staff lands first, and I hop in the Zodiac beside Macduff. Calculating an onshore landing on this beach of sea-smoothed slippery rocks ranging the size of hockey pucks to soccer balls, with no purchase to the stairs leading up to land, the staff quickly motivate and clear a path through rounded boulders and position heavier flat rocks to fashion a safer landing and gentler pathway for the guests. Once they escort guests from hand to hand to gain safe footing, and climb the steps to the bluff above, we follow a raised bright yellow metal path — no, as much as the path and a blue sky indicates, we are not in Oz. The path straight ahead leads to the lighthouse, the hand-hewn log chapel Stella Maris, and the modest caretaker’s home, and autographed flags brought by visitors from around the world festoon the upper lookout. The path to my right leads to the sculpture honoring those lost at sea. The sculpture designed by Chilean sculptor José Balcells Eyquem in 1992, is a prominent structure of jagged cut steel placed on a promontory overlooking the sea. Its shape seems like a heart torn open, but on closer look, the negative contour within depicts the form of an albatross in flight—the seafaring symbol for souls lost at sea. The very winds that bedevil sailors trying to round the Cape, are the essence of life for the albatross who soar on wings spanning up to 11 feet wide. Rising into the wind then descending downwind, a dynamic soaring in which the energy gained from the shear wind allows the great bird to glide over 600 miles without once flapping its wings. Wind is their chariot.

Leading to the sculpture is a plaque with a poem written in Spanish by Sara Vial:

I am the albatross that awaits you

At the end of the world.

I am the forgotten souls of dead mariners

Who passed Cape Horn

From all the oceans of the world.

But they did not die

In the furious waves.

Today they sail on my wings

Toward eternity,

In the last crack

Of the Antarctic winds.

Once we complete our visit, I find myself seated in a Zodiac next to Efrem Ghirmai, 1st Navigation Officer, raised in Sweden who also swam in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics representing his country of origin, Eritrea. He tells me he needed to come ashore to make a pilgrimage to pay honor to those who had lost their lives. When I comment that it must be an emotional moment, he nearly wept. Yes. For most of the guests it was a halcyon day on a pretty part of Patagonia. But he knew a deeper truth of this harsh, uncompromising land, and of a fathomless sea that held so many young lives.

Lighthouse at the end of the world

We clear customs and immigration (moving between Chilean and Argentinean territories) then cross a windy open ocean to get to the Isla de Los Estados, a nature preserve, closed to the public. But Lindblad, through years of responsible tourism, gained special permission. The lighthouse on the east end, San Juan de Salvamento, inspired Jules Verne to write The Lighthouse at the end of the World.

A condor perches high above us on a sheer rock wall while Shayne also points out a ledge splashed with bird guano as a pair of Magellanic Cormorants guard their nest and squawk at us newcomers. I note their distinctive black back, and white chest.

We traverse the island at a narrow waist of land and arrive at a sandy beach on the opposite shore, careful not to bother the nesting kelp gulls at the ends of the strand. A guest hands Rob a multi-bulbous, golden, translucent, strand he identifies as a squid egg sac, that to my eye, conjures up the multi-breasted Artemis goddess of Ephesus. This evening in recap through a microscope projected on the many screens in the Ice Lounge, Katie and Jesse show us infinitely small sea creatures that live 30-100 meters beneath us through a ROV underwater camera.

Glacier Alley

We ply the Beagle Channel, in a stretch known as Glacier Alley where seemingly narrow passages resembling a series of overlapping triangles open onto wide flat seas. The toothy tips of mountains untouched by the weight of accumulative ice retain their spiky profile. Beneath lie the softened contours of landforms shaped by glacial movement. At Beaulieu Cove in Pia Fjord, the sky is shades of white, a wedge of cloud pulls apart like cotton candy and pokes its tip into a horizontal layer of brighter cumulous, and the wedge mirrors the trail of scattered bergie bits in the still water toned turquoise from meters deep glacial silt in this sheltered bay. A cascade from the Romanche Glacier pours into the channel.

Twin slender waterfalls like long white tresses on russet hills delineate the contours of the land.

While on the surface in this fjord, between intervals of fierce wind, there are moments of sublime stillness, in between storms, moments where time seems upended or suspended. Darwin had his first sight of glaciers when the Beagle reached the channel on January 23, 1833 and wrote in his field notebook “It is scarcely possible to imagine anything more beautiful than the beryl-like blue of these glaciers, and especially as contrasted with the dead white of the upper expanse of snow.”

In Garibaldi Fjord, in Alberto de Agostini National Park, at the tippy tip of the Andes, we cautiously approach the mammoth Garibaldi Glacier. Kevin points out wavy bands of gneiss that resemble the marbled endpapers of an 18th century Spanish book of poetry. Then facing the glacier, he notes a brownish strip indicating the medial moraine where two glaciers converged. Rumble and thunder as we witness ice hemorrhaging into the water. The terminus is fractured beyond cubism, more like chinks of marble that have been whacked up, down and sideways. I see the sunlight glinting off this shatteringly beautiful glacier, knowing that we are witnessing its demise with each calving, each iceberg shed to float unattached in a rising sea, making wonder of the blue light within.

Glaciers seem to weep out of the earth. Over time countless layers of snow that resisted the sun, bore down, and compacted the ice so heavily that the bottommost layer begins to slide. The downflow is called a glacier. We are witnessing the death of glaciers. Born in the various ice ages, beginning 2.5 million years ago, glaciers carve the Earth, an arduous millennia-long task of re-sculpting the land, softening crags, depositing moraines, dropping erratic rocks, creating U-shaped and polished valleys, and lakes in their path, entirely new vistas. They bear the weight of frozen time until they at last shed their last icy cloaks. The ice age is coming to an end. Having completed their work, and melting, glaciers release fresh water held fast for thousands of years, ultimately merging with saline water, as a new unknown relationship between land and sea level is taking shape. The arc of a glacier’s lifespan is hard to fathom, as we humans measure the passage of time in mere centuries.

Glacial flour permeates the water and remains in suspension, absorbing all colors of the spectrum save an icy aqua. A glint of blue from a calving glacier may be the only color in a tonal vista. We pause in our Zodiac in a field of bergie bits and icebergs and simply listen. Air trapped thousands of years ago snap, crackle and pop, as it is released, the musical coda of tinkling music, a soft adios.

An Adventure at Tierra del Fuego

The highlight of the trip was to visit Karukinka founded in 2004. Vast expanses of wetlands and the world’s southernmost subarctic boreal old growth forest, a vast complex of wetland systems, alpine meadows, and over a thousand species of flowering plants, mosses, and lichen, and more than 225,000 acres of carbon sequestering peat bogs. Peat bogs cover only 4% of the world’s surface, but they contain twice as much carbon as all of the world’s forests.

Old growth lenga (Nothofragus Pumulio) beech trees thrive— unique southern beech forests evolved millions of years ago on the island continent of Gondwana, that include parts of today’s New Zealand, the southernmost Andes of South America and Tierra del Fuego. On thin soil these shallow-rooted slow growing forests are now protected along with guanaco, fox, and elephant seals that haul out on its beaches. It’s hard to imagine that this pristine acreage was destined to be logged out and the logs ground into sawdust for paper pulp and press board until Goldman Sachs acquired 680,000 acres as part of a bad-debt package previously owned by the US based Trillium lumber and real estate company. John O’Leary, United States Ambassador to Chile, returned to legal practice, while committing himself to environmental preservation. He helped negotiate to keep this expanse of old growth forest as a natural preserve through a partnership between Goldman Sachs and the Wildlife Conservation Society. Macduff and I had visited in 2004 when Goldman Sachs commissioned him to create a photographic document of the area.

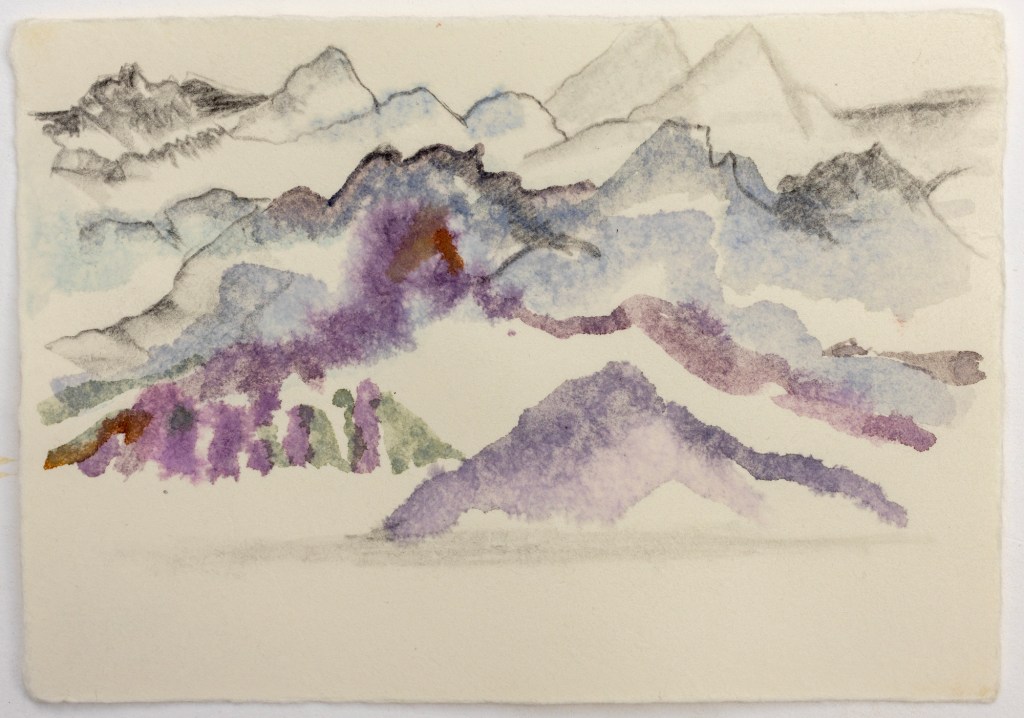

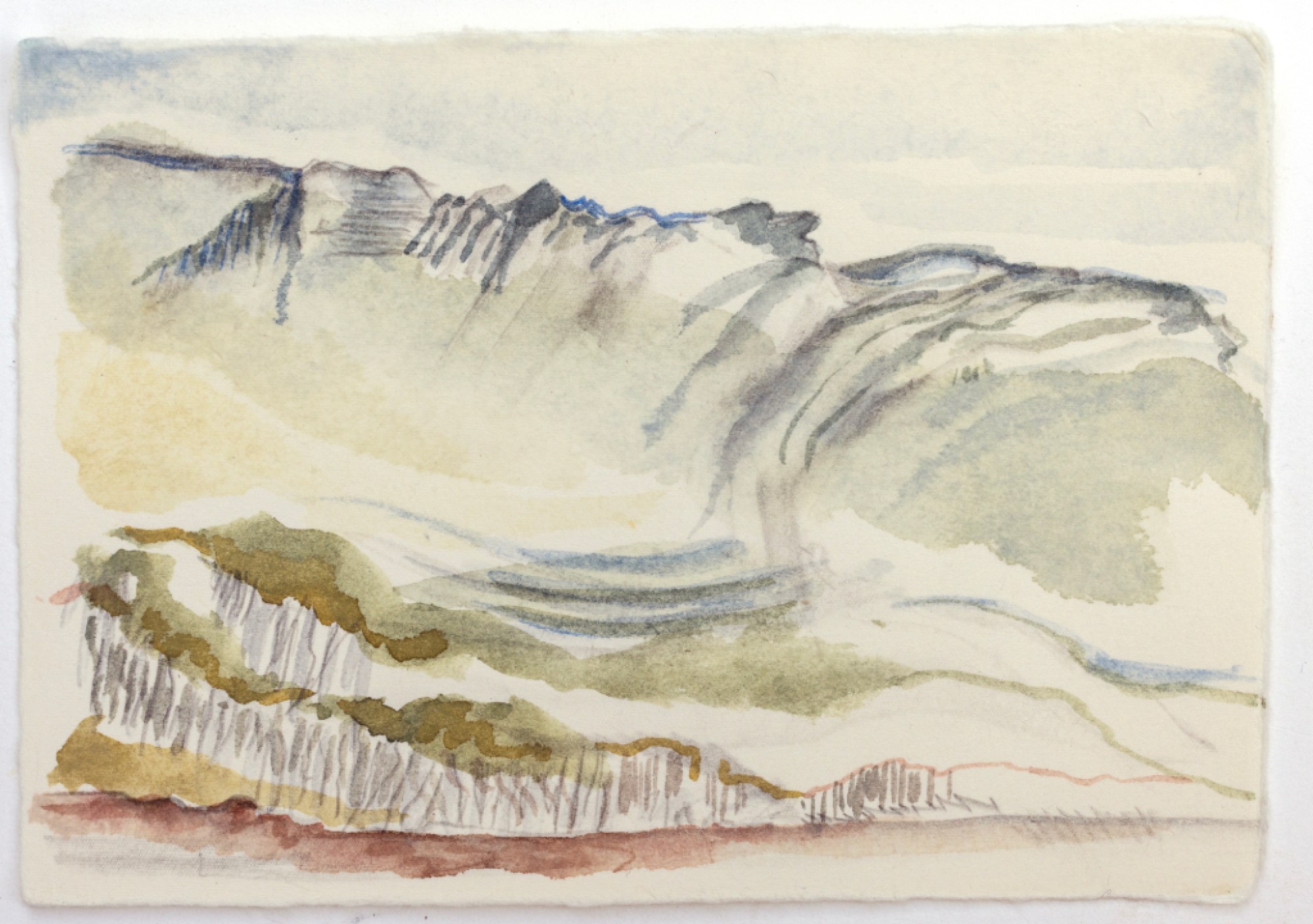

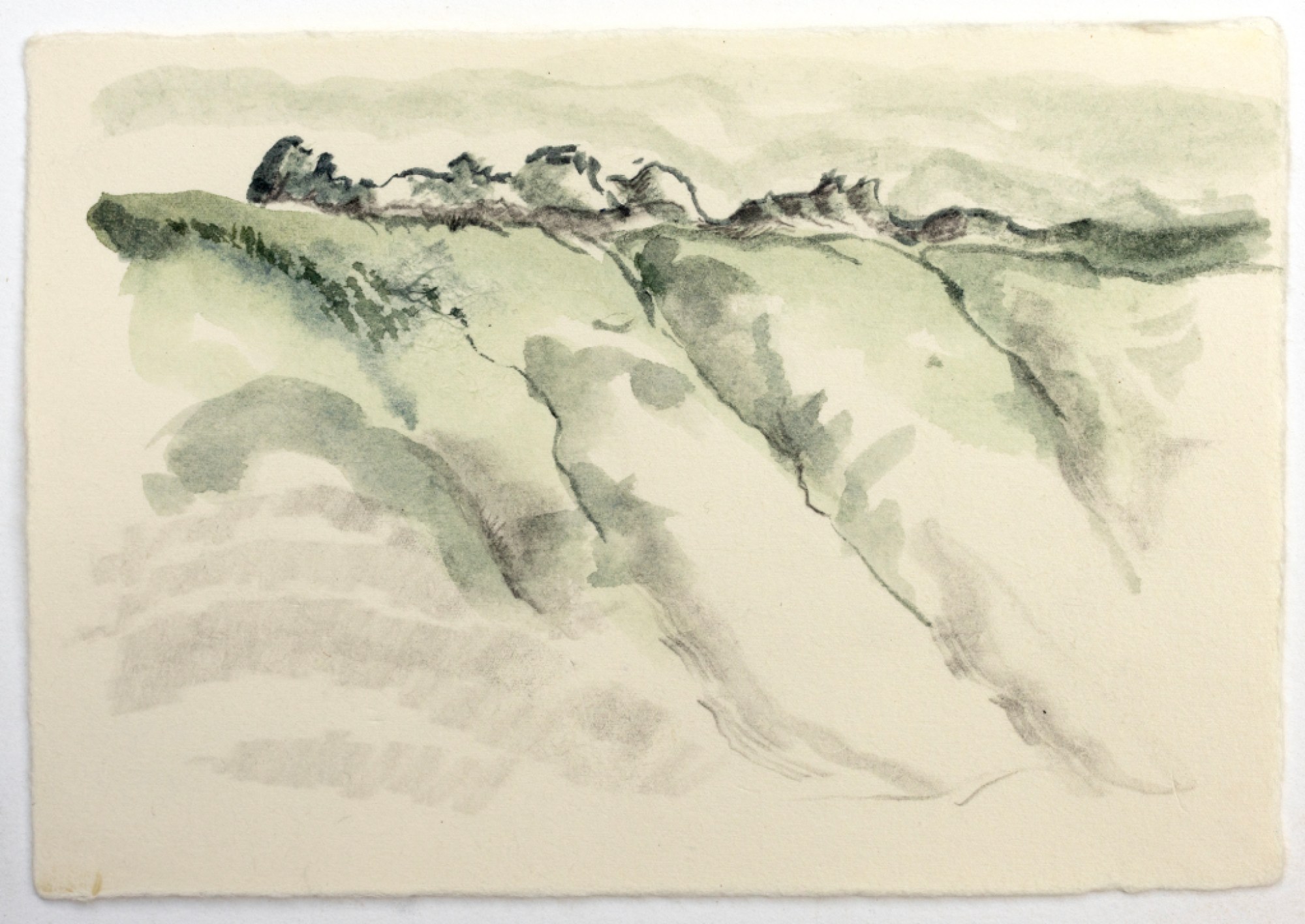

We approach Karukinka with much anticipation. But high winds gusting over 50 knots prevent us from safely landing, a real danger of the wind flipping the Zodiacs. Taking off my layers, wet gear, and wellies, I sit on a table outside and sketch vanishing moments of beauty, as our ship sails past granite peaks folded like taffy, and mountains created by strata, layer cakes of time.

A good friend of ours says that it’s not an adventure till something goes wrong. So, we are now in store for an adventure. The expedition leader and captain scramble to find an alternative site for us to land out of the wrath of Zephyr. They find a bay with a long beach strewn with kelp, mussel, clam, and limpet shells, segueing to marshlands, all with a view to a stunning glacier. On a scouting trip the guides report back to the ship that there are pathways of sorts. We will have a safe wet water landing and time enough to explore this heretofore uncharted patch of land.

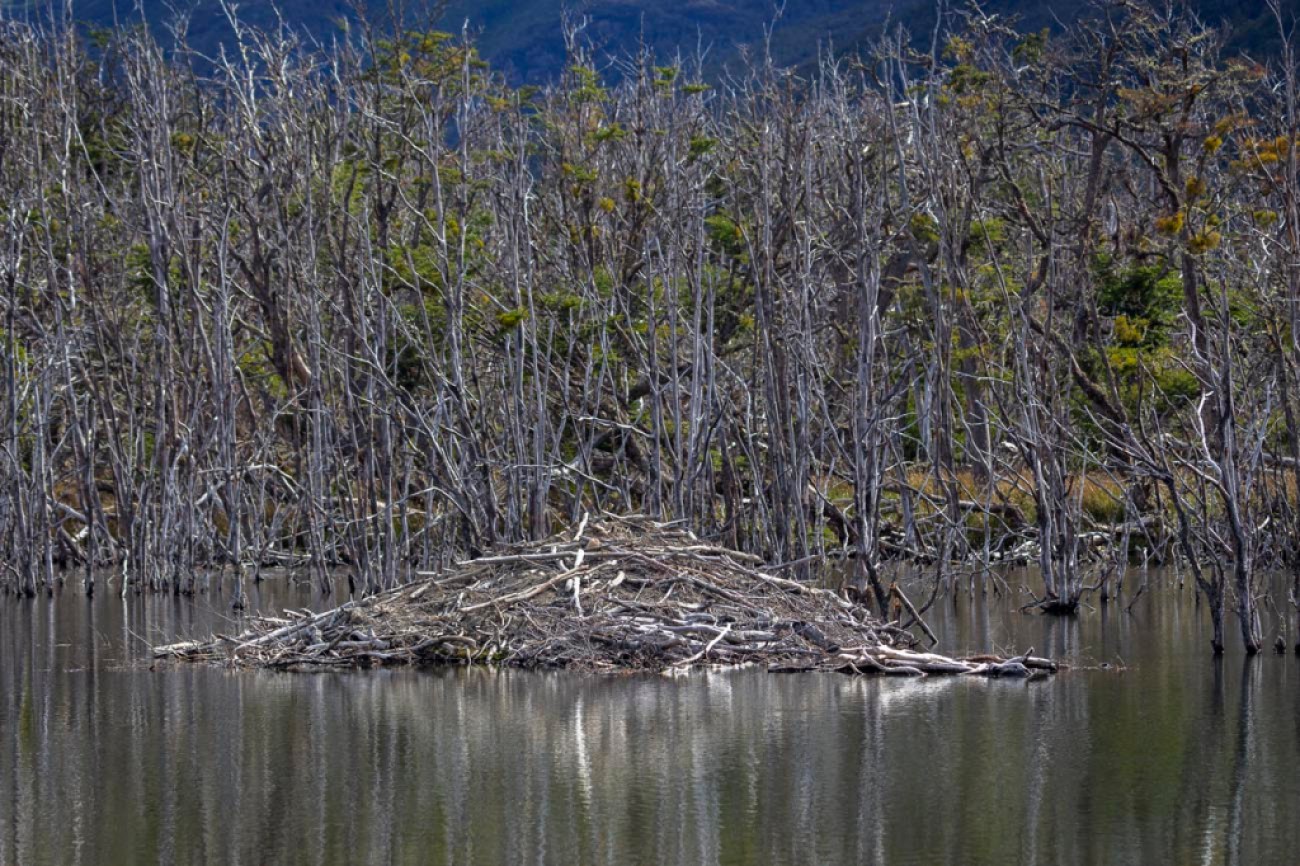

I join a dozen others following tall, long-legged-naturalist-Dan as we slog through a bog marsh of brackish water, ponds, mud, and hummocks, trying to keep pace. I cling to tufts of juncus and catch my balance on patches of tough grasses, gingerly stepping on lichen-crusted rock, skipping over fallen logs —more evidence of the industrious work of beavers, who have plagued Tierra del Fuego and who are busily altering this terrain exclusively to suit their own needs. From an inland pond, the mirrored image of the glacier appears then vanishes in a ruffled breeze.

Master builders wreak havoc

In 1946 the Argentine military flew 20 beavers from Canada to Tierra del Fuego, thinking they could provide income and stimulate a lucrative industry in the fur trade. However, few people trapped the beavers and with no predators to keep population in check the beavers thrived and multiplied to over 110,000, each of them busily gnawing away on old growth indigenous forests to create their dens and dams, profoundly and irretrievably altering this landscape. Unlike Canadian forests, that have evolved responses in order to preserve themselves from the relentless beaver-builders, such as re-sprouting, building a tolerance to wetter soils, and producing defensive chemicals to repel the beaver, these native forests never developed such defenses, so the animals handily overwhelm these trees, and the damage is irreplaceable. Musing on all the havoc they create, my thoughts turned to Robert Moses, the master builder, who from 1920s through 1950s bulldozed, excavated, and utterly rebuilt New York City, to fit his vision, that include bridges, 416 miles of parkway, 2.5 million acres of parkland, public pools, and waterways. To accomplish this, he displaced over 500,000 people, mostly working class and defenseless poor. This thought circles me back to Jackie, our shipboard historian. Karukinka means “our land” in the language of the Selk’nam, one of the original nomadic people who lived in Tierra del Fuego. In the late 19th c. Europeans began a campaign of extermination against the indigenous tribes and today the Selk’nam are considered extinct as a tribe. So, not unlike these native forests, they had evolved no defenses when invaded by European pathogens and alien ways of life.

Reflections

We are in an era where history, geology, and the time lapse imagery, shared by glaciologist Andreas, can better show how drastically and rapidly it is all occurring.

We are on the precipice of change. How can we de-center ourselves in order to accept our part in an interrelated biosphere? Our task seems to be how to embrace the natural world and hold within us both hope and despair at the same time. Being cynical or glib is too easy. The harder work is to keep faith in one another, to remain clear-eyed facing an unknown future in this deeply complicated world.

I turn back to the shore, wanting time to explore the sandy beach, notice the imprints of flow patterns of waves, the prints of goose and seagull, dried seaweed, mussel, limpet, and clam shells. I delight in the free-roaming sense of adventure, excitement and wonder of a guest family’s two young sons, as they busily traverse little streamlets, trace patterns with sticks in the wet sand, as their parents keep a watchful yet distant eye giving them free rein to discover this patch of earth on their own. Their focus, intelligence, and openness to living in this moment, affirms the conviction that we have to open our hearts to change and to care for one another and this place we call home. Strong, joyful, unafraid, and open to all life has to offer them. This is the future.

Hugs, thanks, and gratitude as we disembark the National Geographic Resolution and leave for the airport. We have explored, while afterwards returning to our luxurious accommodation, savored delicious and varied meals, hung out on the Bridge, tried out the sauna and hot tub, and have had numerous engaging adventures and conversations with guests and staff alike.

We may or may not cross paths with these travelers again, but this expedition has touched us, opened our eyes to a shared experience, so that we may regard this magnificent planet anew.

How to get there:

Lindblad National Geographic Expeditions to Patagonia

Follow Macduff Everton’s schedule for his upcoming trips.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.