Nearly 700 Units of Housing Proposed for La Cumbre Mall

City of Santa Barbara’s 60-Foot Height Limit Emerges as Bone of Contention

Santa Barbara Mayor Randy Rowse knew going into last Thursday’s meeting of the Santa Barbara County Association of Governments (SBCAG) just how many friends he had in the room.

Absolutely none.

Rowse, it would turn out, had been overly optimistic.

“I didn’t really enjoy it too much,” the mayor would later say of the experience.

Rowse sits on the SBCAG board — as do the mayors of the county’s eight incorporated cities as well as all five county supervisors. He was hoping to secure a $1.1 million state grant to underwrite a two-year master planning process for the future of La Cumbre Plaza, the open-air shopping mall where as many as 2,000 housing units are now officially envisioned for construction.

Rowse was opposed in his quest by Jim and Matt Taylor, the father-son team of developers who only the day before had submitted a preliminary application to build 685 units of housing on the site. Matt Taylor testified that the Specific Plan planning process advocated by Rowse and City Hall’s two highest ranking land-use gurus — Eli Isaacson and Dan Gullett — was not only unnecessary but would slow things down, thus delaying the provision of desperately needed workforce housing.

County Supervisor Das Williams, who for years served with Rowse on the Santa Barbara City Council, described the city’s proposed master planning process as an exercise in futility.

“I have spent many, many months, years of my life, in the City of Santa Barbara’s planning process that went nowhere,” Williams complained.

Planning efforts that promised to bring the community together and generate unity, he charged, delivered neither; progress, he said, was impeded. City Hall leadership, Williams contended, tolerated a culture in which “design review commissions run amok,” adding, “It is a horrifying thing to watch.”

Williams’s remarks, Rowse conceded, got under his skin.

“I think he was a little hyperbolic,” Rowse said. “This idea that City Hall can’t be trusted and is going to just screw things up, I find a little disturbing.”

Rowse noted how City Hall managed to approve a new workforce housing project for downtown State Street in record time without a single syllable of discouraging words by any of the city’s “amok” design review boards.

“And not to toot our horn,” he added, “but we also helped pave the way for more new rental housing in the last five years than we did in the previous 60.”

By contrast, Rowse had nothing but glowing words for the Taylors, their development team of architect Brian Cearnal and consultant Ben Romo, and their groundbreaking plans for La Cumbre Plaza. But, he cautioned, the Taylor partnership is just one of three ownership groups with a major stake — and major development plans — for the 31-acre mall.

“I’m sure that whatever they eventually build will be first rate,” Rowse said. But, he added, “This is a project that’s going to be there for decades and decades. What the Taylors are talking about will be here at least 75 years. We have to make sure we get this right even if that were to mean pushing things back a few months.”

What Jim and Matt Taylor are now proposing is by itself the biggest single housing development — dubbed The Neighborhood @ State and Hope — Santa Barbara has ever seen: 685 units, six levels above ground, on 8.79 acres. The development as proposed would demolish the mall’s three-story Macy’s building and its associated parking lots and landscaping — sending the city’s last remaining “Great American Department Store” the way of the dodo.

But that doesn’t include the hundreds of proposed new units also expected to be soon unveiled by the two families — the Panizzons and Riparettis — who have owned the adjoining Sears property since the pre–La Cumbre Plaza days when it was still a bucolic dairy farm. They reportedly recently signed a long-term ground lease with American Residential, a housing development firm headquartered in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Two years ago, the Sears owners were openly contemplating the development of 540 housing units on their acreage. Complicating matters further still, Macerich — the third largest mall operator in the United States — holds a lease on much of the mall’s commercial and retail storefronts, and that doesn’t expire until 2077.

Since 2009, La Cumbre Plaza has been written into Santa Barbara’s general plan — the equivalent of the constitution for land-use development — as the biggest and best undeveloped housing site within city limits. For developers, that’s made the long-underperforming mall a cross between the Holy Grail and Moby Dick — infinitely alluring, dauntingly complicated, and financially fraught all at the same time.

Several developers have tried to tie up La Cumbre into one big manageable package; none have succeeded. But on Thanksgiving 2021, a partnership led by Jim and Matt Taylor bought 15 acres of the site’s 31, backed by the Mandrake Capital Group.

The Taylors operate on a national scale — having gotten in on the ground floor in the early days of Costco — and are now in the processing of developing a major subdivision by Lake Tahoe. They also have deep local roots. Jim Taylor moved to Santa Barbara from Chicago with his family as a teenager in 1963; he attended San Marcos High School and lived next door to developer Bill Levy — then also a teenager — who would later give Taylor his first job in the development world. Today, Taylor and his son run American Capital Management, have offices upstairs in El Paseo, and are involved in plans to build the Surfliner Inn, the proposed hotel in downtown Carpinteria that sparked the unsuccessful ballot measure to stop it in November’s election.

Over the years, Taylor — smart, gregarious, shrewd, and given to occasional bursts of off-color humor — made a point to remain strategically below the radar, never courting media attention and avoiding it where possible. Even now, he prefers to give his son the microphone at official gatherings, like last week’s SBCAG meeting. But given the scope and scale of The Neighborhood project, that may no longer be possible.

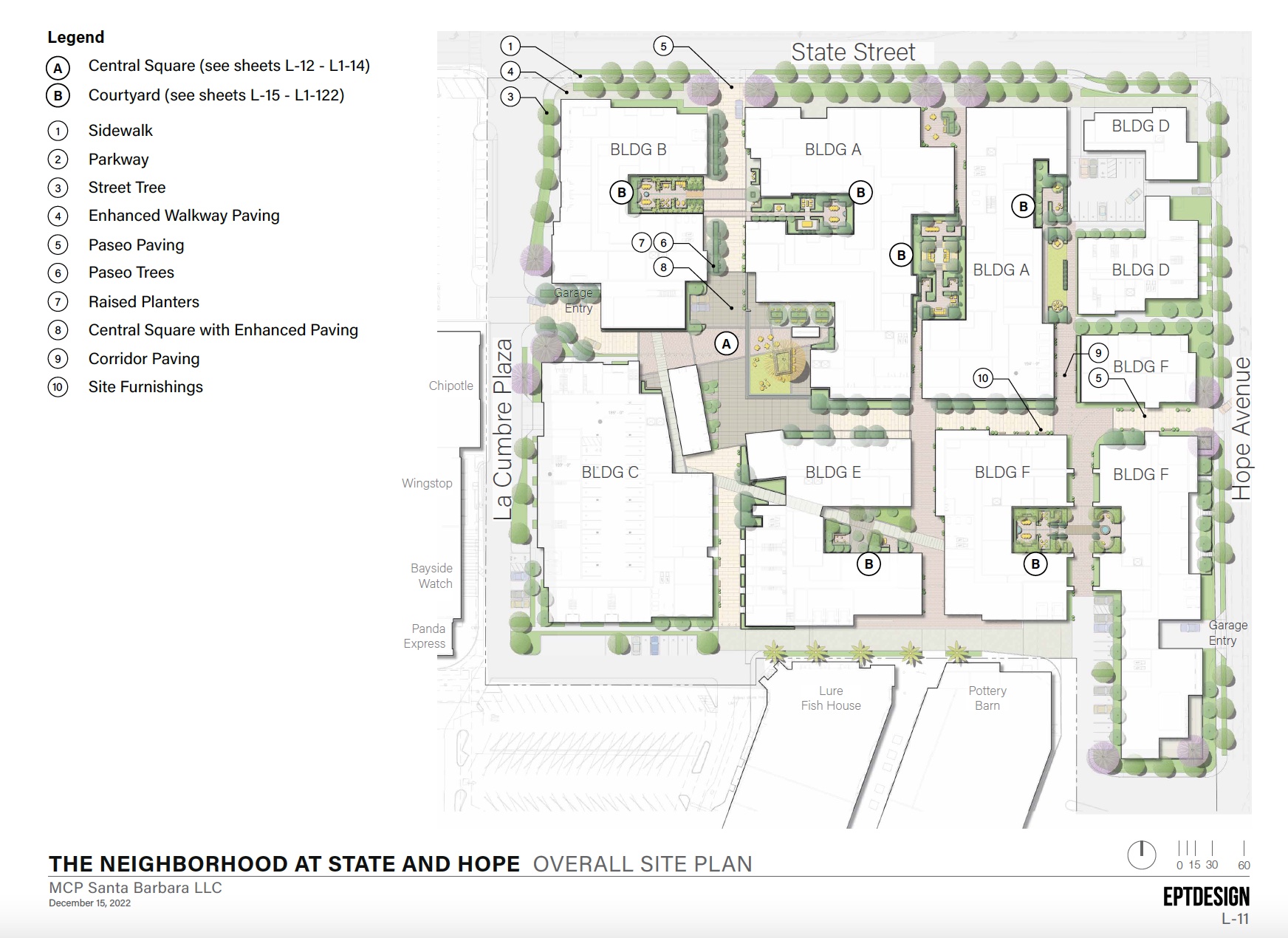

As envisioned, the Neighborhood will be more than just another development project; it will, in fact, be a new neighborhood. On the drawing boards are nine new buildings ranging in height from two to six stories. Already built are two below-ground levels of parking, one space per unit.

Architecturally, the Neighborhood will offer a blend of the traditional and the modern, some Moorish in style, others Mediterranean.

The preliminary application submitted last week highlighted what Taylor describes as “elements of discovery,” paseos and corridors that lead to landscaped public gathering places, including a large outdoor square and a public garden space.

While about 250,000 of commercial retail space will be eliminated, the Taylors will retain about 27,000 square feet of retail.

Under existing zoning, 548 units of housing can be built on the site. But under new state law — which offers density bonuses to developers willing to provide affordable units — the Taylors’ partnership can build 685. Of those, 646 will be rented out at market rates. About half will be one-bedroom rentals with an average size of 716 square feet. Perhaps 142 will be set aside for seniors. Fifty-six of the units will be affordable. Of those, 39 will be affordable to those deemed “very low income,” with the balance targeting those whose incomes qualify as “moderate.”

The most obvious and immediate rub will be height. Right now, the existing zoning limits building height at La Cumbre Plaza to no more than 45 feet. The maximum allowed anywhere within city limits under the city’s charter — and approved by city voters in 1972 by a margin of 3-to-1 — is 60 feet. Elements of the proposed new development are envisioned as high as 74 feet. Without such elevations, the Taylors say, as many as 50 of the proposed units cannot feasibly be built.

But if you listen to Mayor Rowse or the city’s Community Development Director Isaacson, the City Council could not legally approve anything beyond 60 feet — even if they wanted to — because to do so would violate the city charter, the municipal equivalent of its 10 Commandments. Because the 60-foot limit was passed by referendum, Rowse stated, it would require another ballot election to undo it.

The Taylors insist otherwise, contending that a “Yes, in My Backyard” bill passed in 2019 — the Housing Crisis Act — preempts the city charter.

“The State has declared affordable housing a statewide emergency, and state density bonus regulations apply to charter cities,” Matthew Taylor wrote. “Santa Barbara is not an exception.”

The city’s 60-foot height limit, he said, would effectively preclude the developers from achieving the number of units to which they are entitled under this law. “Trying to build below the current height limitations would result in the kind of blunt architecture we see in other communities,” Taylor objected.

Buttressing Rowse’s remarks, City Attorney Sarah Knecht stressed that the state’s Housing Crisis Act “does not change any local zoning standards.” She noted the city’s 60-foot height limit was written into the charter when voters approved it in 1972. “The charter is the city’s ‘constitution,’ and the height limit established by the charter cannot be changed without voter approval.”

Unless this matter has been clearly resolved in court, Rowse and Councilmember Eric Friedman — who represents the district — caution that the open question could give rise to a possible lawsuit or even a ballot initiative by residents upset at loss of local control.

“Remember how prickly people in San Roque became about Chick-fil-A?” Rowse asked, referring to the public outcry over cars backing up into State Street.

The other big issue left to be resolved is whether City Hall will embark upon the long and cumbersome Specific Plan planning process on its own.

Interim City Planner Gullett said the Specific Plan is necessary to better integrate whatever the Sears owners want to do with what the Taylors hope to build. By addressing thorny issues like open space, creek setbacks, floor area ratios, height, traffic circulation, and impact on the neighboring Hope School District up front, he argued, developers will enjoy a degree of clarity, certainty, and flexibility to respond to shifting market conditions many years hence.

“We’re looking at a once-in-a-100-year situation to make this really good for the city as a whole,” Gullett said.

But with 17 percent of City Hall’s planning positions currently vacant, such an undertaking would prove challenging in the extreme for in-house planners. Conversely, $1 million is a lot of money — particularly as city budget planners are girding for budget cuts — to hire outside help. Either way, the Taylors argue that a Specific Plan would hold up their development and could add an element of undue risk beyond the $250 million they say the project will cost to build. It’s far from obvious if there’s council support to pursue that approach.

The one thing the Taylors and City Hall all agree on is the need for more housing. “We all want the same thing,” Rowse said. “We just have different ways of getting there.”The vote, by the way, at last week’s SBCAG meeting was 10-to-1 against funding the city’s Specific Plan. Rowse cast the sole vote on the city’s behalf.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.