Words to the wise and to the wary: Depending on your cultural leanings and affections, the experience of watching the first half hour of Tár may vary wildly between love, awe, tedium, and even a strong desire to flee the theater. But rest assured, the shrewd, dramatic schematic of writer-director Todd Field’s brilliant film will ultimately pull any serious moviegoers attention into its expert, thriller-tinged clutches.

Basically, anyone invested in the rarefied world of classical music — professionals, music-lovers, critics, scene-watchers — may find themselves ecstatically alarmed by the authenticity and insider savvy of the film’s classical milieu. Seldom, if ever, has there been a major motion picture that delves into the classical music sphere without groan-some artifice.

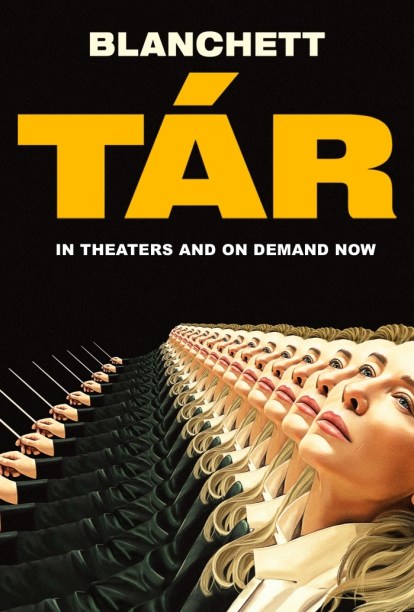

Narrative and cultural scene issues aside, at the experiential epicenter of the film is another remarkable performance by Cate Blanchett, delivering possibly the greatest performance of the year in American cinema. (On a local note, Blanchett thankfully returns for a deserved tribute at the upcoming Santa Barbara International Film Festival, on February 10, 2023).

Blanchett sinks deeply into the role of Lydia Tár, globally famed conductor (call her maestro, not maestra, please) with more than a touch of neurotic and manipulative inner machinery. We meet her at a New Yorker Festival interview event (with the real Adam Gopnik as interrogator) and then in a long but critical scene as she teaches conducting students at Juilliard. There, she works on a new piece by the established Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdottir, and segues into a touching scene of Bach-love with Blanchett herself playing the Prelude No. 1 in C of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier while giving a blow-by-blow analysis.

Much of the film takes place in Germany, as she rehearses the Berlin Philharmonic (okay, it’s actually the Dresden Symphony) for a recording of Mahler’s mythic Symphony No. 5. The symphony itself is fraught with conflicting emotional terrain, complicated by cinematic association: As they practice the famed slow movement, she hollers, “Forget Visconti,” referring to director Luchino Visconti’s heavily thematic use of the music in Death in Venice. Mahler-ian drama and angst also invades the life of our protagonist/anti-heroine, in a way loosely reminiscent of the dance-world meltdown of Natalie Portman in Black Swan. Tár slowly frays and unravels, partly haunted by mysterious and disturbing sounds in her periphery (the sound design of Tár is one of its many stellar attributes).

Aspects of power plays and sexual harassment allegations stir up the real life #MeToo recriminations ending the careers of conductors James Levine and Charles Dutoit. Ugly realities in the classical realm rear their heads and lend chilling veracity to the fictional comfort zone of the world of Tár.

Field, whose lean, distinguished, and left-of-center filmography also includes In the Bedroom and Little Children, and who is also a musician, brings his obvious obsession with classical music’s “otherworldliness” to bear, in uncommonly artful ways in Tár. Classical music is beautiful and life-enriching, the film seems to surmise, but the world in which it lives is not always pretty.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.