The COVID-19 pandemic may loom less menacing now than it did two years ago, but we are not out of the woods yet. As of this writing, new cases are still being registered each week in Santa Barbara, on top of growing reports of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Furthermore, in the race to distribute vaccines, enforce public health mandates, and sort through the political clamor, we have yet to fully take stock of the devastating toll the pandemic brought on our communities.

Sadly, this is not the first time that a contagious malady of global proportions has visited pain and suffering upon the people of Santa Barbara. In 1918, an influenza pandemic, which became popularly known by the problematic misnomer of “Spanish Flu,” wreaked havoc and caused deaths of an estimated 675,000 people in the United States.

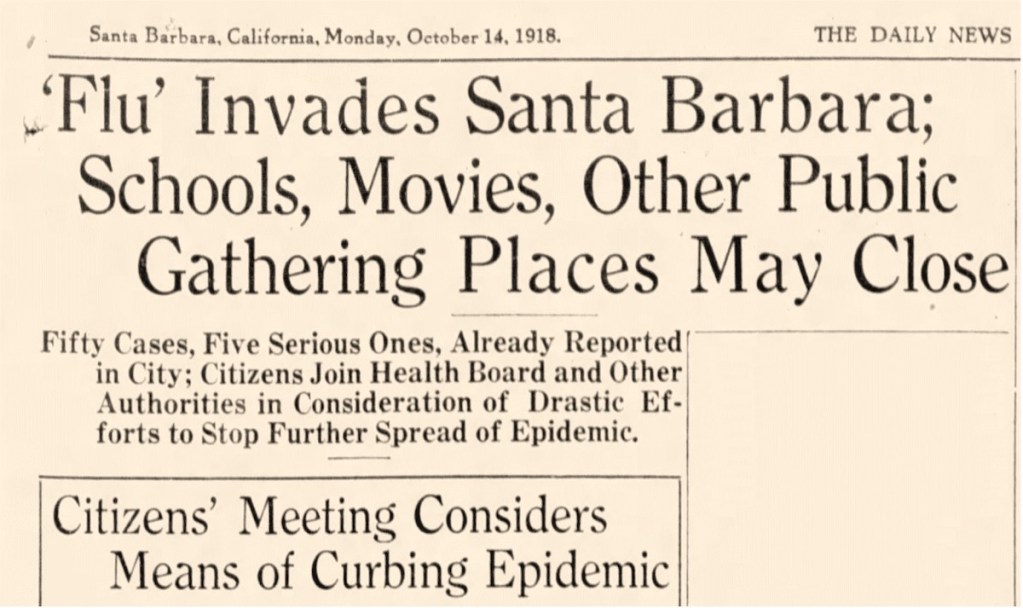

Archival records suggest that the influenza pandemic arrived in Santa Barbara in early October 1918. At the time, approximately 25,000 people lived in the city. According to local historian Betsy J. Green, approximately 625 people contracted the flu and 19 people succumbed to it. On October 15, the Santa Barbara Board of Health took drastic action and declared a ban on public gatherings. Schools, churches, and movie theaters closed their doors. Halloween and Thanksgiving came and went under the specter of a deadly virus.

To protect the population and contain the spread, health officials in Sacramento issued a statewide mask ordinance on October 23. It applied to “all barbers, dentists, and druggists” as well as “every doctor, nurse, attendant or visitor within a hospital” who provided medical care to influenza patients, “members of every family in which a case of influenza exist[ed],” and those who experienced “any of recognized symptoms of influenza.” Finally, the state recommended spraying the gauze masks with “a bichloride of mercury,” a toxic chemical compound that was used as a common household disinfectant in the early twentieth century.

In Santa Barbara, the so-called “Mask Law” went into effect on November 11. The law required the “traveling public” to don a mask of “approved style” when boarding “street cars, taxi cabs, buses, and other public conveyances, including elevators.” City police were given direct orders to arrest individuals who disobeyed the law. A string of controversial arrests soon followed. For instance, a physician named Dr. J.B. Clifford was taken into custody for failing to wear a mask on a street car.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

Santa Barbara’s Board of Health declared mandatory quarantine of “all houses containing influenza cases” ― such households were required to place window placards warning the public to keep their distance ― and opened a so-called “vaccine depot” at the downtown San Marcos Building, where healthcare workers administered “three inoculations, two days apart” at no cost to those wishing to get vaccinated.

These precautionary measures, however, could not stop the spread of the dangerous virus to St. Vincent’s orphanage, which had cared for orphans from California’s Central Coast since 1858. Local press reported on the outbreak with an ominous headline – “Epidemic Gives Orphanage Hard Hit.” According to reports, of the 80 “tots” that were in the care of the orphanage, 66 had contracted the virus by late November.

The crisis at the orphanage engendered extraordinary acts of kindness and charity from the people of Santa Barbara. Local doctors would visit and monitor the condition of the children on a regular basis. Several nurses worked hand in hand with St. Vincent’s sisters to provide the sick infants with round-the-clock medical care and comfort. Others donated money, goods, and food.

The generosity of the community as well as the commitment of the Daughters of Charity averted a potentially devastating outcome. A news report published December 6 declared that “the situation at St. Vincent’s orphanage is greatly improved, no new cases having been reported in the last four days. The children who are ill are recovering rapidly.”

With the tide of the outbreak turned at the orphanage, St. Vincent’s focused its energies elsewhere in the city. When Cottage Hospital, St. Francis Hospital, and County General Hospital exceeded their capacities, patients requiring urgent medical care were taken to the emergency hospital at Boyland, originally a boarding school built in 1913 on the Riviera. Still, local inpatient care facilities were sorely needed, especially for families with young children. So the Daughters of Charity opened the doors of St. Vincent’s Day Nursery to “children whose parents [were] afflicted with influenza.”

The 1918 influenza pandemic upended a way of life that thousands of Santa Barbarans took for granted and left behind a trail of pain and grief. At the same time, the public health crisis brought forth compassion, kindness, and acts of extraordinary generosity and courage from all corners of the community.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.