Goleta History | Dos Pueblos Chumash

Two Distinct Populations at the Mouth of a Storied Creek

The original version of this story was posted on September 22, 2022; it was revised and re-posted on November 29, 2022. The story first appeared at GoletaHistory.com.

Dos Pueblos is Spanish for “two villages,” but to locals, that’s the name of our high school.

And the name of a ranch on the outskirts of town. But why would this ranch and our high school be named “Two Villages”? Good question….

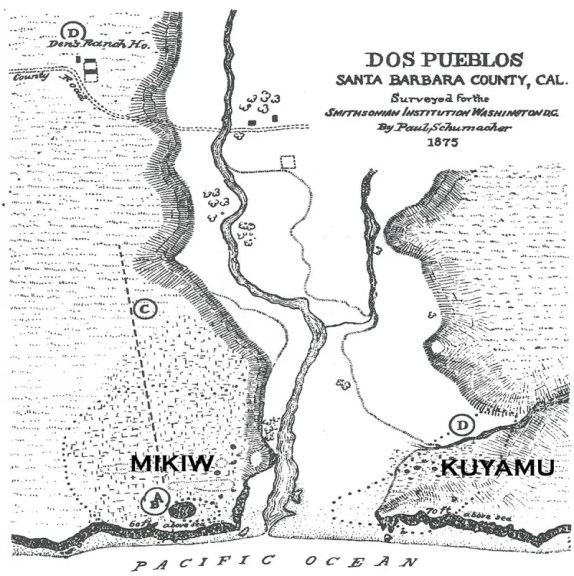

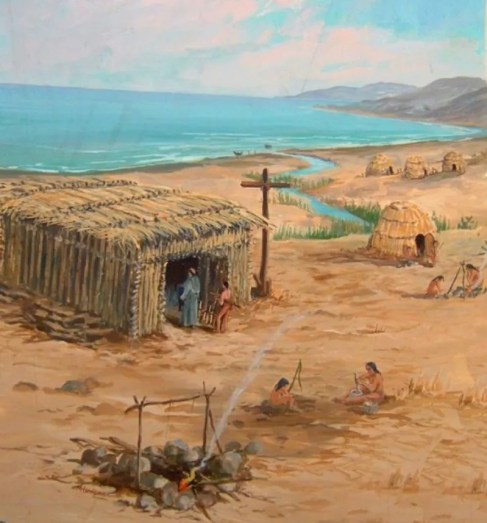

Dos Pueblos is in fact the oldest place name in Goleta. In 1542, the first European explorer to cruise the coast of California nicknamed this area Dos Pueblos because there were two Chumash villages right next to each other. The two villages in question were 10 miles west of Goleta at this picturesque location on the coast. They were called Mikiw and Kuyamu, and they were here long before any Europeans came along and gave them a generic name.

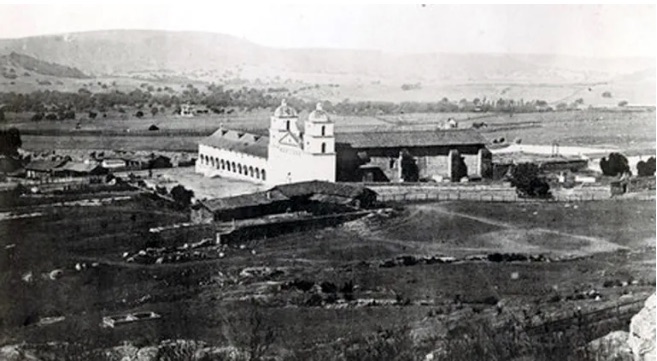

This aerial shot from 1936 shows where the two villages were located. Modern anthropologists believe the reason for two different villages to be situated in such close proximity was the abundance of food available from the thriving Naples reef just offshore. Obviously, food availability was a very important factor in choosing a village site.

But for decades, common folklore was that these two villages had very different cultures and even different physical characteristics. There was just a small stream and an estero between them, but despite their proximity, they supposedly spoke different dialects and had different cultures. The villagers were not allowed to cross the creek without first getting the other tribes’ permission.

One of the earliest published local history books from 1880, Thompson and West’s History of Santa Barbara, amplified the folklore, writing that the people of the two villages had different physical characteristics. The people of Mikiw were thought to be tall, slender and a light complexion. The Kuyamuns were thought to be shorter, sturdy and darker skinned. This story originated from Rosa Den Welch, the widow of the Dos Pueblos don, Nicolas Den. Rosa related the story to archeologists working at Dos Pueblos in 1875, stating that she heard the story firsthand from an elderly Chumash woman that was still alive at the time. The story was published in multiple history books and was taken to be fact for many years.

While this makes for a very interesting story, modern historians say it most likely was not the reality. Like many oral histories, a good story lives on and even gets more detailed through the generations. Maybe moving further from the reality and more towards myth. In 1925, respected archeologist David Banks Rogers tried to find some real evidence of two different peoples in the villages of Dos Pueblos, but due to decades of grave robbers, excessive previous archeologist digs and erosion, no solid proof could be obtained one-way or the other. We do know for sure that they lived next to each other for hundreds of years, but the two towns were politically independent of each other. Anthropologist John Johnson has linked the two tribes genealogically, proving that the two tribes did indeed interact amicably, including inter-tribal marriages.

Noted ethnologist John Harrington interviewed Chumash survivors extensively in the early 1900s, and they did confirm there was a “Dos Pueblos dialect” that made their language a bit different than the villages in Goleta. But none of the interviewed mentioned the story of two neighboring villages at Dos Pueblos that had two different languages and didn’t get along.

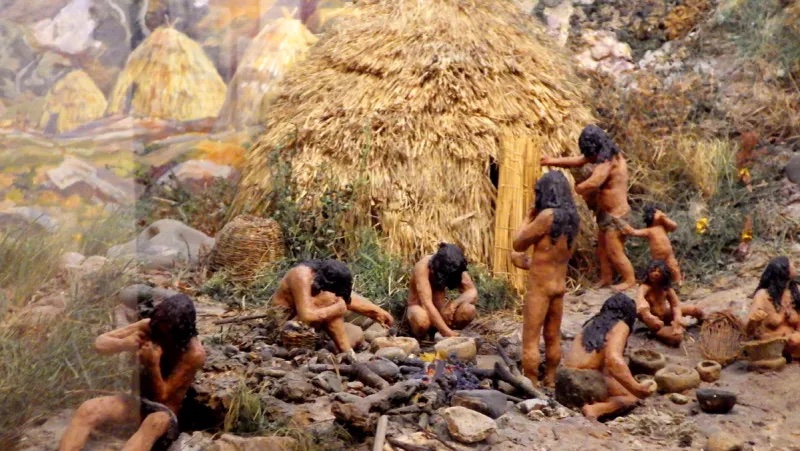

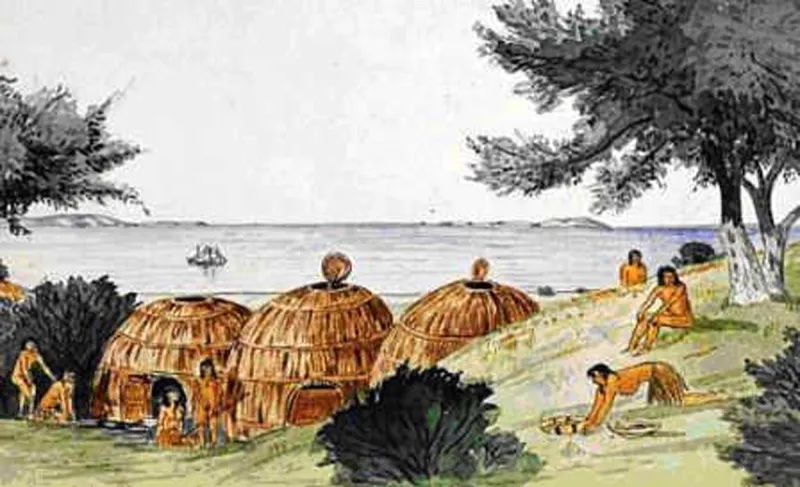

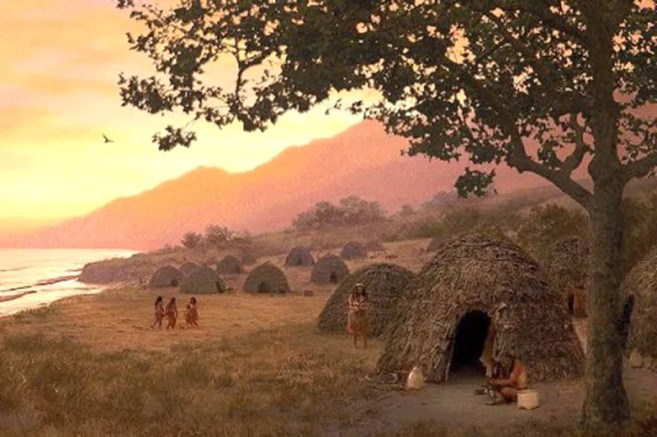

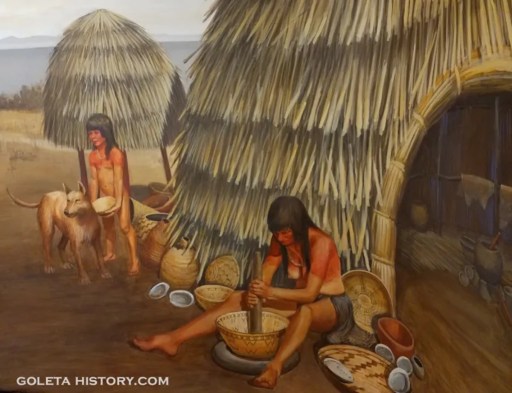

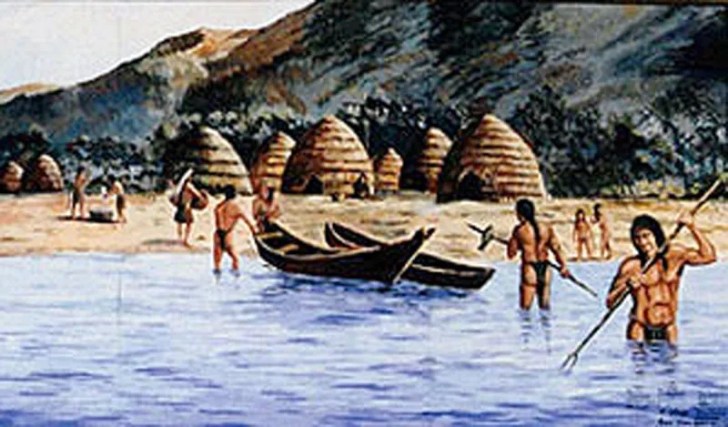

In the exposed cliffs below Kuyamu was a trickling stream of asphaltum, a great asset to that tribe. It was used for a multitude of things by all the Chumash villages, including the construction of their impressive watercraft, the Tomol. Their houses were described by European explorers as a half an orange with an open hole for chimney ventilation and light at the top. They were made of a frame of long poles, woven with grass and reeds, and an animal skin would be used to cover the hole during heavy rains.

Unlike most early Californians, the Chumash slept in framed beds raised off the ground and they covered themselves with skins and shawls. Sometimes multiple family members would share a house. Their villages were laid out in an orderly fashion, with a number of different structures besides houses, they had larger buildings that were sweat lodges, which were built near fresh water to jump into after sweating. They also built windbreaks, structures for storage, dance floors, and sacred enclosures for ceremonies.

While we like to imagine the Chumash as living in a perfect world, the reality was not so idyllic. Being human, they surely had their problems too. Social inequality was apparent, as there was an upper class, middle class and lower class, distinguished by their apparel. Additionally, many Chumash villages had ongoing disputes with some of their neighbors.

Spanish journals from the 1770s mention the near constant fighting of some tribes, the most common disputes being about trespassing and women. The normal method of warfare was by ambush or late-night attacks. The Chumash living at the Dos Pueblos were reportedly seen as “troublemakers,” and some witnesses described seeing them with scalps from other Chumash they had killed. The villages at Dos Pueblos were also victims of raids, and one report says the attackers came from inland specifically to attack Kuyamu.

The Arroyo Quemada area, just up the coast from Dos Pueblos, is named after a village that was burned while the inhabitants slept. According to the journal of a Spanish Governor, the natives from Dos Pueblos were responsible. The same journal states that the Dos Pueblos and the village on Mescaltitlan Island were “declared enemies” that fought viciously and often. So often, in fact, that the Spanish considered putting the Presidio in between those two villages, instead of in Santa Barbara, to prevent the constant fighting.

Many other tribes got along well with one another and trading was commonplace between them. There were alliances with villages from different areas up and down the coast and deep in the inland valleys.

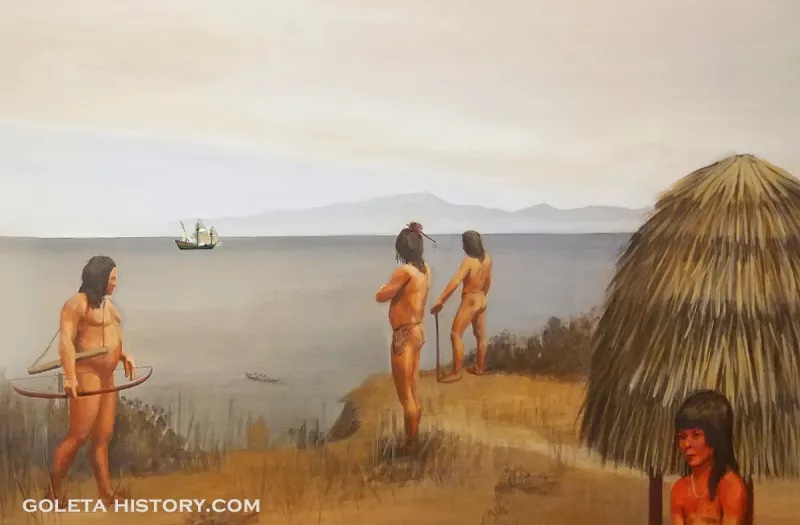

When the Europeans appeared in the Santa Barbara Channel, they were more than welcomed by the natives. Their friendliness toward the explorers was overwhelming. From village to village, the natives rushed to greet the explorers with gifts of whatever they had to offer.

Were they just a naturally happy people, eager to share their paradise with strangers? Or were they hoping for a powerful new ally in their ongoing battles with rival tribes?

Most modern California history books start with Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo cruising up the California coast under the Spanish flag. In fact, Walker Tompkins calls the day Cabrillo anchored off the Dos Pueblos the day history began. But for the Chumash, it was really the beginning of the end.

Cabrillo’s two ships, La Victoria and San Salvador, dropped anchor off Dos Pueblos in the late afternoon on October 16, 1542. The huge ships with giant billowing sails must have been an overwhelming sight to the natives, but they probably heard of their approach from fellow Chumash to the south.

Cabrillo had seen and visited many native villages on his six-month journey up the coast, and he knew if he let his men go ashore, the Chumash hospitality would put them further behind schedule. His purpose for stopping here was just an overnight anchorage before resuming his search for the mythical Northwest Passage. The entry in Cabrillo’s log this night read, “anchored in the evening opposite dos pueblos.” And so it was: The name was born, the oldest name in the Goleta area.

Cabrillo and his men watched as the friendly natives paddled their tomols out through the surf to greet them. They had seen this for the past week, as they had been escorted by the Chumash on these speedy canoes all through the Santa Barbara Channel. They were loaded with gifts of fresh and dried fish, baskets of acorn meal, and so on. The Europeans usually reciprocated with glass beads from Italy, brightly colored cloth scraps, and other worthless trinkets. But this day, Cabrillo was under the pressure of winter approaching and supplies dwindling, so he had to refuse the natives’ invitation to come ashore.

At the crack of dawn, Cabrillo was off, across the channel to check out the islands. Historians can’t agree on the details of Cabrillo’s final days, but it is believed he continued on around Point Conception, where they encountered rough seas and foul weather. The expedition made it as far as the Russian River but retreated back to the Santa Barbara Channel for refuge.

At some point, Cabrillo broke a bone and did not care for it properly. Gangrene soon took over Cabrillo’s battered body. When they made camp on one of the California islands he passed away, just a few months after his visit to Goleta. Many believe he is buried on Catalina Island, others believe he was buried on San Miguel Island, in plain view of the villages at dos pueblos.

The people of Mikiw and Kuyamu went back to life as usual after the strange visitors left, and their memory slowly faded. Amazingly, 227 years passed before another European made direct contact with their world. Generations were born and died with the legend of the hairy-jawed white men on giant canoes.

A few large ships passed by over the years, but they stayed well off the coast and probably were not noticed by many. Imagine those few telling others what they think they saw and being met by skepticism, much like a UFO sighting today…

The mid 1700s brought invaders from another corner of the world. Russia had claimed Alaska, and they quickly realized the value of the sea otter pelt. By the end of the century, aggressive Russians enlisted Aleutians and Alaskan natives to help harvest the pelts and they were soon seen hunting in California waters.

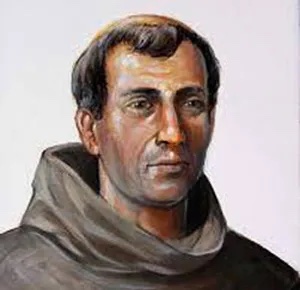

This handsome gentleman, King Charles III of Spain, did not like having Russian operatives off the coast of his Northern Mexican provinces. He decreed that Alta California needed armed defenders, ASAP. Spain came up with a three-pronged plan: presidios, missions, land grants. Thus, a land expedition was put together to determine locations for the presidios and hopefully find a good harbor for the Spanish Navy.

A Catalan soldier, Don Gaspar de Portolá, was put in charge of the expedition that left San Diego in July 1769. His group consisted of chief scout and trailblazer Sgt. José Francisco de Ortega, Father Juan Crespí, many soldiers and Baja California natives, and 100 mules carrying supplies. There were 63 people in all. In the late afternoon on August 21, 1769, the group came through the oak groves to Dos Pueblos Creek where they stopped to water the livestock.

The scout, Sgt. Ortega, was the first European to set foot on the soil at Dos Pueblos, and he greeted the awestruck people of Mikiw and Kuyamu. These Chumash were the great-great-grandchildren of the Chumash that welcomed Cabrillo two centuries before. The Chumash were especially amazed by the great beasts these fancy men sat upon. Horses had never trod upon Dos Pueblos before, but they would play a huge role in its future, as would young Sgt. Ortega…

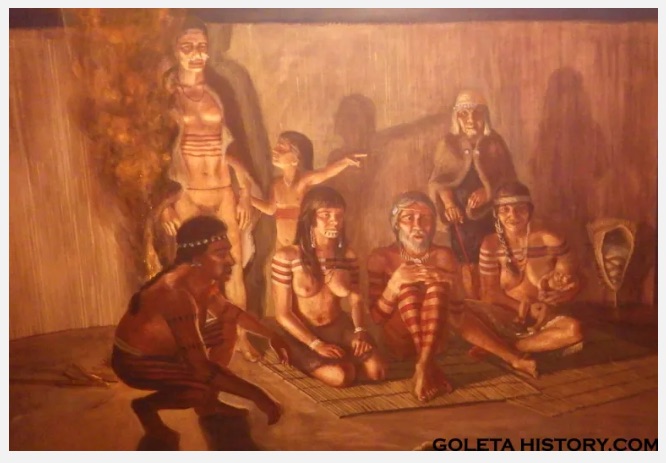

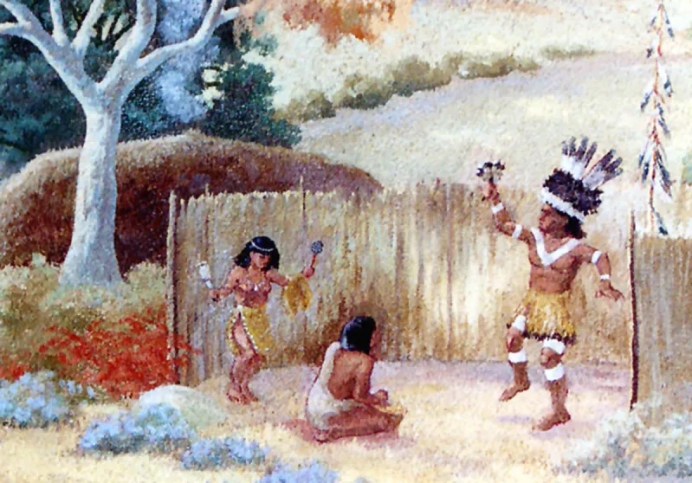

Portola kept a journal, and he estimated each village to have 60 houses and about 800 people. Fr. Crespi also kept a daily log and he described an Indian settlement of no less than 600 souls. Crespi officially named the dos pueblos “San Luis Obispo de Tolusa,” but it didn’t stick. The explorers camped near Kuyamu and were immediately greeted with gifts of fresh fish. They had been welcomed at most every village since Malibu and were growing weary of the all-night parties.

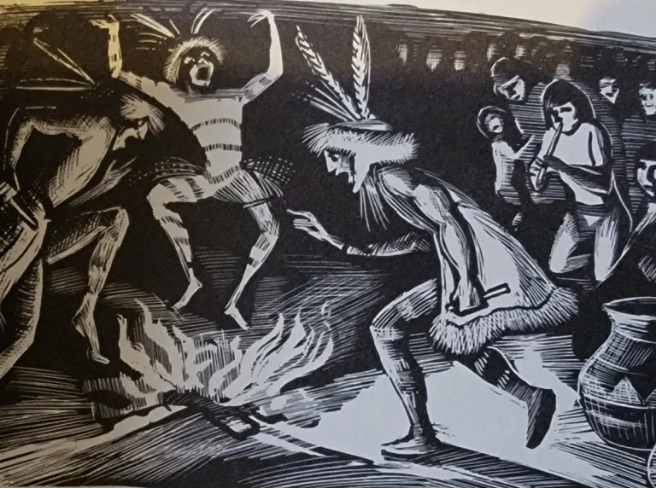

Fr. Crespi described how the Chumash at Dos Pueblos were not satisfied with providing the visitors with fresh fish but also wanted to entertain them. The chief came with split reeds that when shook served as a rhythm instrument to accompany their chants and dances, all through the night.

The Europeans begged the Chumash to let them sleep, and sent them away, but they returned later in the night blowing some sort of horn that Crespi says, “was sufficient to rip our eardrums to pieces.” The soldiers feared the horses might stampede and they quickly gave the Chumash some beads and convinced them to let them sleep.

Despite the wild party, the Portola expedition stayed two nights, giving them a full day to get a good look at the area surrounding Dos Pueblos. Juan Crespi wrote that this site would be an excellent location for a shoreline mission with plenty of fresh water and limestone.

Portola wrote in his journal that the natives here seemed more civilized than others: they had many “canoes,” and he noted they slept in beds. He also made some notes about their cemeteries and how there were multiple chiefs in each town. He also wrote that each chief was allowed two wives while other men had only one.

Portola’s group moved on, and a few years later, in 1774, Juan Bautista de Anza and his expedition camped at Dos Pueblos. The Chumash probably began to realize these foreigners were not going away.

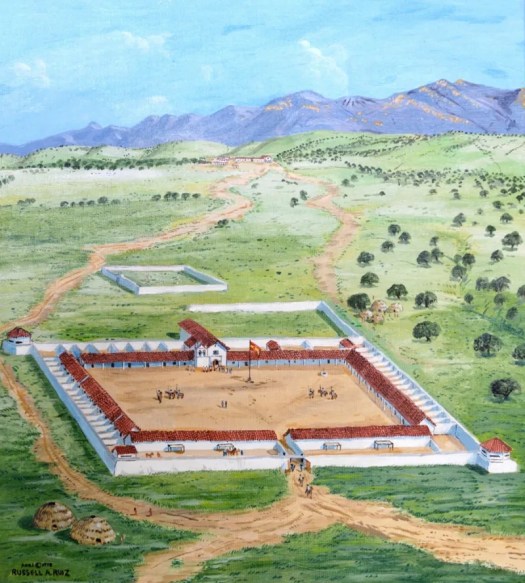

In 1782, the Spaniards built a Presidio near Chief Yanonalit’s village in Santa Barbara and the comandante was Jose Francisco de Ortega, the scout from Portola’s expedition and a friend of the Dos Pueblos Chumash. A permanent Spanish military base didn’t have an immediate effect on the natives, but four short years later, the mission was built, and that’s when things really went downhill for the Chumash.

Father Fermín de Lasuén constructed, with Chumash labor, a small adobe church near the Royal Presidio and was ready to start saving souls.

While life at the Chumash villages in the area didn’t immediately seem different, the natives had no idea that they were now living on a Royal Rancho, claimed to now be property of the King of Spain. They would now be expected to cultivate their land, plant, farm and harvest crops, to help support the cause of the mission. To people that had lived off the bounty of Mother Nature for centuries, this surely seemed absurd. Unfortunately, they didn’t have much choice in the matter.

Even more ridiculous was the order that they should leave their comfortable homes at beautiful Dos Pueblos and go live in adobe rooms in rows of apartments at the mission! The Chumash elders were not eager to give up their ancient traditions, but some of the younger generation may have been more easily influenced. The mission fathers were offering a reliable food source and a safe place to live, two things that required effort in the wild.

The missionaries were determined crusaders and they fervently believed they had to save these pagan souls. The fathers regarded the land they controlled as being held in trust for the Indians that would be turned over to them eventually after they were established in Spanish ways. Of course, this never happened.

In 1769 Portola’ estimated close to 1,000 people living at Dos Pueblos. Just 25 years later, a census counted 210 people living there. Most residents had been convinced to move to the mission and work for the padres and soldiers, or they had died from European diseases. As the mission lands expanded, more livestock were grazing on open lands, slowly devouring the very plants and seeds that the Chumash had depended on for survival for centuries. Some Chumash chose to keep living in their ancestral villages after they were baptized, but their food sources were slowly disappearing, and now they had fewer hands in the village to help them gather food. The old way of living became nearly impossible.

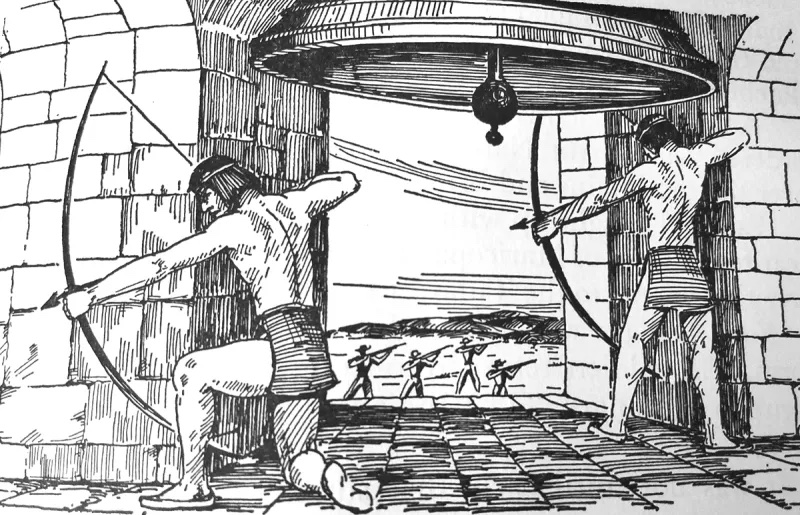

In February of 1824, some natives at Santa Ines Mission were angered by an unjustified flogging, and they attacked some soldiers in retaliation. The word quickly spread down to Santa Barbara, where mission neophytes feared retribution from the soldiers. They armed themselves with bows and arrows and sent the women and children into the foothills to hide. A brief battle ensued, killing two Chumash, but they managed to hold their defensive positions in the mission. The soldiers took a midday break for a siesta and to strategize, which allowed the renegade Chumash a window to escape. They fled into the canyons to join their families.

During all this, four elderly Chumash from Dos Pueblos happened to be walking down to visit Santa Barbara the same day, oblivious to the warfare. When they arrived in town, angry soldiers attacked them and they were shot and killed in front of multiple witnesses, simply for being Chumash. The news of this attack sent most of the few remaining at Dos Pueblos packing into the mountains, as far as Buena Vista Lake, which was near today’s Bakersfield. Four months later, the padres issued a pardon and most of the Chumash returned to the missions.

In 1837, a young Irishman named Nicholas Den rode through Dos Pueblos and fell in love with the area. He vowed to own it one day and went to work for the Ortega family at Refugio, supervising Chumash laborers. Den had studied medicine in Ireland, but never got his diploma. Since there were no doctors in Santa Barbara at the time, he became very much in demand as a doctor. He helped all walks of life and took pay only when they could afford it. He saved a lot of Chumash lives and befriended many of them. He made an effort to learn the Chumash language, and they taught him about their medicinal herbs, which he put to good use.

After much hard work and jumping through all the political hoops, Den was awarded the Rancho Dos Pueblos land grant in 1842. He considered himself a friend of the natives, and he allowed some Chumash to live on their ancestral lands at Dos Pueblos in the traditional houses of their people. Den lived a good long life here and his last action on this planet was to save a Chumash life.

He left his sick bed in the middle of a cold stormy night to assist a Chumash woman giving birth at El Capitan Point. After he managed to save the woman’s life, he journeyed back home through the storm. The next morning, Den died from double pneumonia. His Chumash friends and employees assembled outside his window and sang an ancient sacred chant, reserved for the passing of a high chief.

The Dos Pueblos Ranch changed hands through the following years and several prominent archeologists came and studied the Chumash remains. Dr. Yarrow did an extensive dig in 1875 and took over 10 tons of artifacts from Dos Pueblos and other Goleta areas. He reported arched whale bones above the graves at Mikiw and some 30 skeletons buried on the bluff in beach sand. Archeologists were baffled by the reasoning to carry about 5 tons of sand up the 60-foot bluff for burial rites. Fifty years later, famed archeologist David Bank Rogers found the same sand at this location.

By 1925, much of the village site of Kuyamu had already fallen into the sea due to normal erosion, but Rogers happened to be working on this site when the Great Earthquake of 1925 hit. He describes watching a large portion of the village site dropping into the sea, all at once. Forever erasing untold amounts of historic information.

Further up the canyon he found remnants of a village from thousands of years before Mikiw and Kuyamu. Rogers called them Oak Grove people, proving this place we call Dos Pueblos has been desirable for eons….

And continues to be so today. If you have enough money, this sacred place can be rented to celebrate your own special occasion.

So, if you’re ever lucky enough to find yourself there, take a moment to imagine how it once was, and remember the people that lived there for centuries before the Europeans came.

Sources: John Johnson, David Banks Rogers, Walker Tompkins, Thompson and West, Alan K. Brown, Toucan Valley Publications, John Johnson, Yankee Barbareno, Jack Elliot, Wikipedia, Glenbow Archives, Pinterest, Researchgate, Paul Schumacher, Ann Thiermann, warpaths2peacepipes.com, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, Santa Barbara Mission archive, William Dewey photography

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.