The Carpinteria community showed up in full force at the South County Housing Element Workshop last week, where planning staff were blasted with questions over the recently released interactive map showing sites deemed by the county as candidates for rezoning in order to meet South Coast housing quotas.

Their message was loud and clear: Carpinterians do not want agricultural land to become housing.

In the scramble to meet the state’s guidelines to certify a Housing Element plan before the February deadline, counties across California are forced to reckon with the reality of expanding their housing markets without expanding their borders. And as the deadline approaches, the consequences grow even more severe: Local governments that do not meet their deadline to certify could lose their discretionary authority to review housing projects, in effect granting developers a near-free pass to build any projects that meet minimum local standards.

For unincorporated Santa Barbara County lands, i.e., those outside the eight city borders, the state allocated a Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA, pronounced “reena”) of 5,664 housing units that must be accounted for — not necessarily built — over the next eight-year cycle from 2023-2031. At least 4,142 of those units must be in the “South Coast” regions, which includes the outskirts of Carpinteria, Santa Barbara, and Goleta stretching from Gaviota to Casitas Pass.

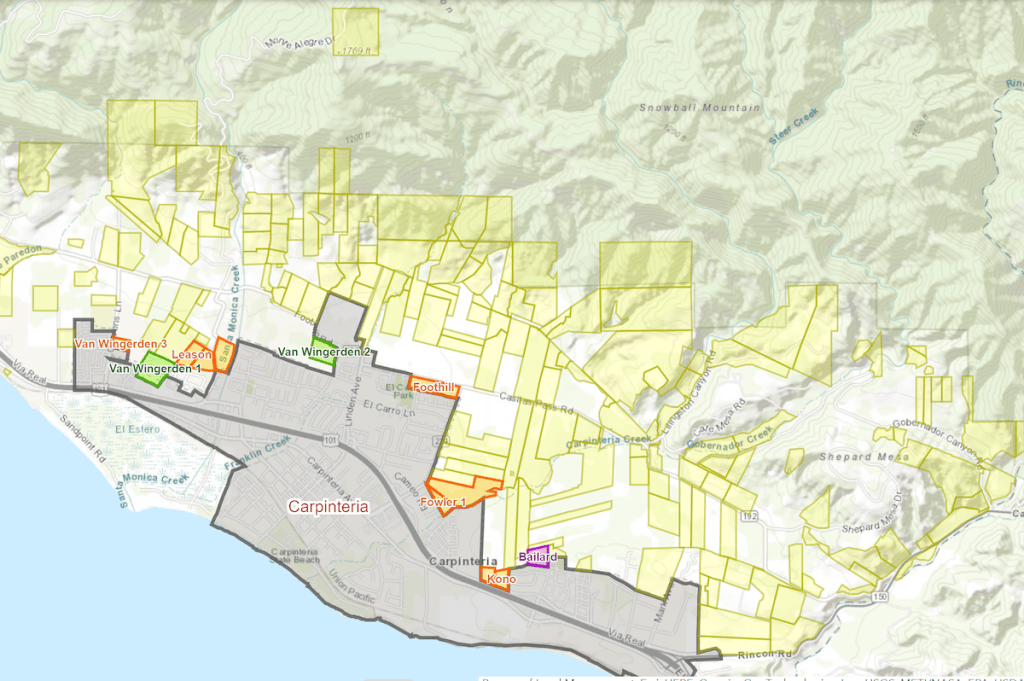

To meet these requirements, county planners took an inventory of properties they deemed “potential housing opportunities,” and assessed which were fit for rezoning to allow for future residential development. All properties that the county examined were included in the interactive map, which allowed users to click each parcel and view details on the sites.

When the map was first released, Carpinteria residents were shocked to see large swaths of agricultural land included. In fact, at first glance it appeared that the bulk of the sites listed sat in a big yellow puddle on the map, all surrounding Carpinteria city limits.

However, Selena Evilsizor Whitney and Jessi Steele, the county project managers in charge of the Housing Element update, explained at the meeting that the “yellow” sites had been considered but discarded for various reasons. The green and purple areas represented sites that were either already in development or likely to be rezoned before next February. Evilsizor Whitney also explained that out of the 11 sites being seriously considered outside Carpinteria, seven were orange — sites that were “potential rezones less likely to result in units by 2031 due to significant restraints” — leaving four that would be rezoned for this cycle.

That being said, she stressed that the map was just a first draft. “We just finished preparing last week and released it as soon as we could,” she said.

Prior to the workshop meeting, a group called Concerned Carpinterians wrote a letter about the proposed rezoning, criticizing the County Board of Supervisors for setting its sights on the agricultural areas around the city. In the letter, the group lists 10 properties currently zoned as agricultural, which according to the map could account for more than 1,000 residential units.

“Rezoning would change the current urban-rural boundary and alter life in the city of Carpinteria and the valley forever,” the letter reads.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

At the workshop, more than 170 attended via Zoom, and even more in person, many of whom believed local officials were overstepping previous decisions to preserve agricultural areas of the county. Some of those who spoke raised questions over the consequences of developing on these parcels, from lack of resources like water and electricity to the buildup of traffic on roads not meant for dense population.

In the online chat during the workshop, attendees switched between questioning the process — why does the state keep raising the housing quotas? What happens if the county can’t zone for all those units? Why was the map just now released? — and hyperbole: “We don’t want more meth, more robberies, and more violence against women,” wrote one chatter about increased farmworker housing outside Carpinteria.

Some asked why areas like Summerland, Montecito, and cannabis farms were conspicuously left off the list of properties considered for rezoning. A few alleged that political interests had swayed which sites were included.

Several of the attendees, including Carpinteria City Planner Nick Bobroff and Mayor Wade Nomura, wondered why Carpinteria seemed to have the lion’s share of parcels being considered for rezoning. Out of the 26 sites that could be rezoned to meet the state’s quota, 11 were being considered in the areas right outside of Carpinteria city limits. Eleven more are in Eastern Goleta Valley, and four are in other areas of the South Coast.

“This increases the county’s ability to tap into city resources,” Nomura said. He said he hopes that the county will work with the local city governments to “take a look at responsible growth” and “consider the impacts,” particularly in the coastal zones which have their own strict standards for development. “Let’s work together,” he said.

In response to allegations that the county had purposefully left out areas like Hope Ranch, Montecito, or cannabis farms, Steele said the county was “trying to avoid converting of all kinds” of properties, and “did not single out in any way trying to avoid cannabis farms.”

Steele also addressed some comments urging the county to fight back against the state’s RHNA system and Housing Element requirement, saying “some local governments have pushed back to no avail.”

Any potential action would have no effect on the impending deadline, which Steele said the county was already on course to miss. “The county is not going to meet this deadline,” she said.

Each city in Santa Barbara County has its own Housing Element, and its own RHNA numbers to account for, and according to a report from the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), both Goleta and Santa Barbara received requests for changes in their initial drafts.

If the county does in fact miss the February deadline, it would lose “subjective” review over projects if developers meet the objective requirements then the project would have to be approved.

Planning staff said they will take the comments from the workshop and move toward updating the Housing Element draft, with the priorities of preserving as much agricultural land as possible and exploring properties that are already close to “urban” environments and resources, but that eventually there would have to be tough decisions made to accommodate future housing needs.

“We cast as broad of a net as we could,” Evilsizor Whitney said.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.