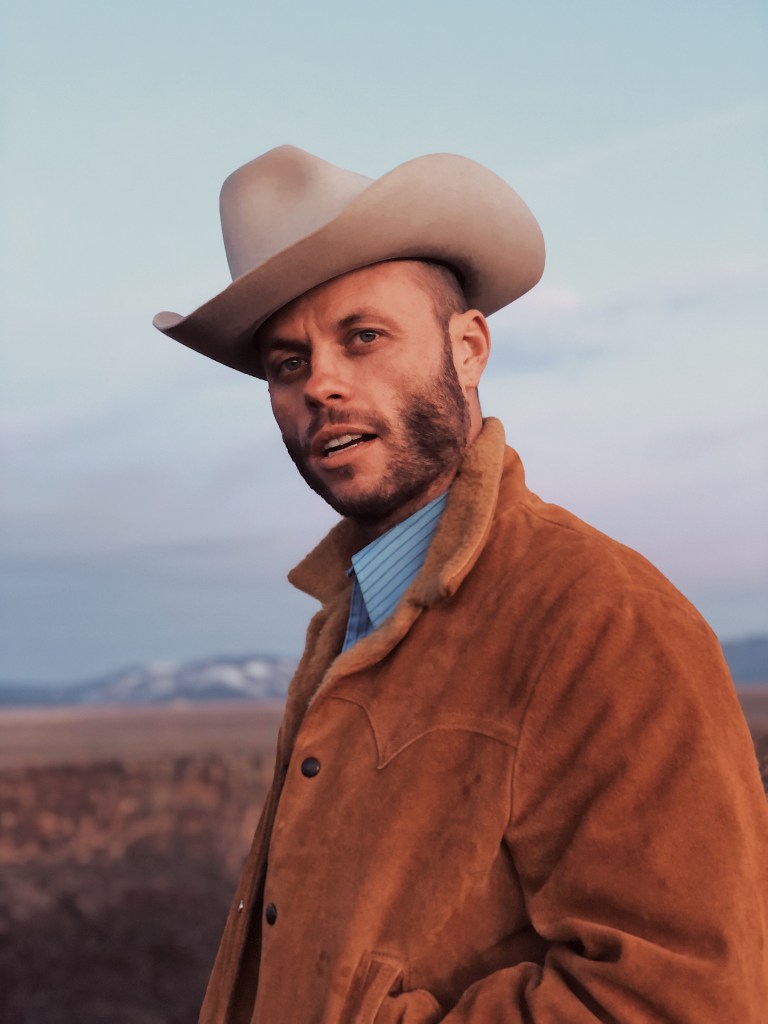

Charley Crockett’s

Country Hits the Arlington

Rising Star Kicks Off Arts & Lectures Season

with His Own Kinda Twang

By Josef Woodard | September 29, 2022

Read all of the stories in our “Fall’s Cultural Harvest” cover here.

For some of us 805-ers, who might be a bit behind the hipster curve, our first exposure to the neo-classic country sensation Charley Crockett came on the airwaves of the San Luis Obispo public radio station KCBX last year. The airplay rotation occasion was a promotional warm-up for Crockett’s big show in the San Luis Obispo venue Alex Madonna Expo Center last November.

His proudly retro yet distinctively now-ish approach to songwriting and production triggered a certain delicious cultural-historical mind-melt, especially for those of us favoring “classic” country over the modern stuff piped over the country airwaves. Touches of archival blues, old school soul, Ray Charles–style, and pinches of Paul Thorn–like drawl and irony are among the other features in the San Benito, Texas–born Crockett’s special musical world.

On Sunday night, Crockett makes his debut splash as a headliner in the picturesque expanse of the Arlington Theatre, and in the high-profile position as opening event of the UCSB Arts & Lectures season. In some way, the choice of Crockett as season launcher may seem a brave maneuver for the series, tipping the curatorial hat toward an artist relatively little-known in the usual A&L circles. In another way, the timing is ripe, catching a distinctive artist in a strong career upswing. He was recently interviewed on NPR and is landing in finer venues around the land. Take the Arlington, for one.

As heard on Crockett’s latest, The Man from Waco — his 11th album in just seven years, mostly on the Thirty Tigers label — Crockett doesn’t fit easily in the fixed format of our day. As one sign of old times, the title song “The Man from Waco” is a murder ballad, a genre Crockett has proudly worked in before in his large and story-filled songbook. Essentially, he’s a man too proudly out of time and passionately history-rooted for the modern country radio format, who sneaks into the Americana world on his own terms, and with a sound tipping its hat to sounds of yore.

In addition to Crockett’s healthy stock of original solo albums, including Welcome to Hard Times and Music City U.S.A. within the past two years, he has channeled his allegiance to past heroes and

trailblazers under the pseudonym Lil’ G.L. The latest entry in that series is this year’s country music tribute Jukebox Charley, bowing to such pioneers and personal influences as Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and Tom T. Hall.

From that album, on his version of the Roger Miller hit “Where Have All the Honest People Gone?” Crockett circles around to his own story when he sings:

The people in this city call me country

Because of how I walk and talk and smile

Well, I don’t mind them laughing in the city

But the country folks all say I’m citified

The fighting men may say that I’m a coward

Because I never push no one around

Gentle people call me trouble maker

’Cause I’ll always fight and stand my ground

Funny I don’t fit

Where have all the honest people gone?

Needless to say, Crockett is a square peg in contemporary Nashville’s round-holed “Today’s Country” scene. On his song “Music City U.S.A.,” in a mantra-like refrain swaddled in pedal steel riffs, he sings, “I shouldn’t have come here in the first place / ’Cause folks here don’t like my kind.”

That said, a growing fan base and critical hosannas are nudging Crockett’s profile ever higher, in a grassroots-y fashion. Among his fans is a major hero, Willie Nelson. In an interview last week, Crockett was in New York City the morning after having opened for Nelson in the legendary SummerStage series in N.Y.C.’s Central Park.

Reflecting on his much humbler days as a musician in the city, as a struggling busker, Crockett, now 38, can appreciate the upward mobility of his destiny, then to now. “Fourteen years ago,” he recalls, “I played on the street here and in the subways, on platforms and subway cars, and in Central Park. I would wander down along the edge of the park, coming down from the Met, and cut over into the park. There were pretty good musicians holding down a lot of the best spots. So I started playing under bridges initially in the park, made a little money doing that.

“The money was a little better last night,” he laughed.

Opening for Nelson in Central Park was akin to a dream come true for Crockett, beyond just the N.Y.C. nostalgia connection. “What could be better for somebody from South Texas like myself?” he enthuses. “Willie paved the way. When you’re on the street corner hustling for change, you’re not thinking that you’re gonna be talking with Willie Nelson. He’s one of the best singers, too. You can learn a lot from him. His phrasing approach is really special.”

After his long haul as a road dog and prolific recording artist over the past seven years, in his studio, Crockett is in a paydirt period. Does he feel a particular satisfaction and sense of vindication these days?

“We’re thrilled. I definitely can feel the change,” he says, but adds, “Am I satisfied? I don’t know. I always want to see what’s over the next hill. I always want to go to the next town and play again.”

For Crockett’s dense fall itinerary, the “next towns” include Santa Barbara (where he last played opening for Sean Hayes at SOhO in 2016), the iconic Hardly Strictly Bluegrass festival in San Francisco, a run in Europe, and landmark country music settings of Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium and the Austin City Limits festival.

Crockett explains that October’s run of shows in smaller cities, such as ours, is part of a grander plan as the stakes rise. “We’ve been staying out of a lot of the big cities that I was overplaying for years.” Playing in places like Santa Barbara and Ashland, Oregon, is, he says, “a buildup for the headline tour that’s coming in November. And those are some of my favorite areas. Santa Barbara has a very Northern California kind of attitude that always stuck out in Southern California. I love L.A., but I love to leave L.A., too.”

Remarkably, Crockett’s slow but steady upward trajectory has come about through an unusually organic process of getting his name and sound out. A man out of time with an out-of-sync, DIY sense of how to navigate his way in the music world, Crockett speaks half-derisively about “the words ‘marketing strategy.’” For a long spell, he explains, “the only source of getting the word out was the live show. Word of mouth is the hard way of getting out there, but I’m proud of it. I’m still doing that.”

And there was another off-the-radar marketing concept he deployed. “I bought some billboards. It was just a harebrained idea that I had because I always wanted to do that when I was a hobo. Oh man, I mean, they were 75 percent off. And, you know, you’d buy one and you pay for 30 days and it stayed up, would expand for four months, because nobody was buying them.”

He commemorates the billboard adventure on the song “Name on a Billboard,” on The Man from Waco, a clever, winking snub of showbiz follies: “Think I’ll buy some things / I can’t afford, hey, look / My name’s on a billboard.”

Meanwhile, back in Manhattan last week, Crockett brought up a very recent encounter with the music machinery now eager to tap into his growing reputation. “I was in a business meeting in Midtown yesterday,” he says, “and hearing the phone ringing all the time. I was talking to these guys who run this big company, and they’re nice gentlemen. But they were trying to convince me to do a record deal with them or something. The guy asked me if I’d ever been to New York before.

“I said, ‘Yeah, I probably played 30 shows here in the last seven years. On top of that, I played the street by the train cars.’ He could have read my Wikipedia page for 10 minutes before I showed up.”

Had the record company man read Crockett’s Wikipedia page, he would have learned a few things about the man and the artist, and the twain between them. He would have learned that Crockett, reportedly a

descendant of Davy Crockett, grew up with his single mother in a trailer park in Texas and summering with his uncle in New Orleans. He leapt into music at 19, picking up on shards of the American music history he would end up emulating through samples in contemporary hip-hop tracks.

As if following a template for “classic country” troubadours, Crockett roamed and hopped freight cars, playing on the streets in America and Europe. Frustrated by his lack of success or stability in music, Crockett landed in Northern California, working in such then-dubious modes of employment as “ganja” farms “way out in the mountains of Lake County, one county inland from Mendocino County.” (Crockett explains that while working as an “itinerant farmer,” he became obsessed with Robert Johnson, beyond his “Delta blues” mythology.)

Like Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash, and others in country annals, he also fell afoul of the law and was convicted of a felony. In 2015, he returned to Texas and to his musical calling in earnest, releasing his debut album A Stolen Jewel. From that point forward, things fell into place, with a lot of hard work and dauntless touring, deepening his songwriting skills and honing his artistic identity.

Especially for artists who rely on the road life for their livelihood — and even a sense of belonging and direction — the pandemic lockdown and live music interruptus factor had a major impact. Crockett says, “It’s something that we all have had to contemplate, in the whole world. I was working so hard for so long. All of a sudden, in that first summer, we didn’t play at all, even the back door kind of country chitlin’ circuit that I came up on. Even that was closed for a few months.

“I’ve been going so hard for so long, here in New York City or in New Orleans, or San Francisco, Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin, Asheville, North Carolina, high Rockies, up and down the California coast. I moved around those towns for years as an itinerant and up and down those highways. When I finally got my first agent, he worked me harder than anybody. I was on the road basically 300 days a year, and I did that for the last half-decade. The motel was the furthest I could see ahead, being able to get enough sleep, get on the highway, get dressed, get ready for that show and do it all over again.

“All of a sudden, in that summer, there was not the option to do that at all. Most everybody was shelved and shelving their albums and postponing them, but we just put one out — Welcome to Hard Times.

“I had written it before the pandemic — start to finish in about a month — in that late winter, right before the pandemic hit, I wrote the record and then recorded it in South Georgia. We found out that South by Southwest was canceled, and South by Southwest is not an event that gets canceled. When we found out about that, I said, ‘Oh, shit, man, ain’t nothing gonna be like it was.’”

Among the personal hard times alluded to on 2021’s Welcome to Hard Times was the singer’s open-heart surgery in early 2019, replacing a valve with a prosthetic model made of cow tissue. Although the album was written and recorded before global COVID-infected “hard times,” the album’s themes projected a resonance naturally touching an expanding body of listeners.

“I always write from a very personal place, even if I’m telling stories, or coming up with fictional characters. It’s all kind of based on my life, and Welcome to Hard Times was just something I had been feeling, being somebody that was kind of working in the shadows from street corners, and the highways. All those visuals, particular songs, that album, that message of ‘welcome the hard times’ was a place or an idea. It resonated for where I was and where it got me. I think people heard that and it spoke to the times.

“Art and artists can shape times, but the time shapes the art, and then people gravitate toward it.”

Clearly, Charley Crockett’s own gravitational pull as an artist is on the up and up.

You must be logged in to post a comment.