What Works in Learning to Read

Consensus Emerging on Best Methods

Many of California’s public schools are failing to teach all of our students to read because they use programs that don’t follow the science of reading. Teacher-training programs ignore science as well.

What works best for most students promotes explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and systematic instruction in phonics and methods to improve fluency and comprehension.

Louisa Moats, a national reading expert, writes: “The body of work referred to as ‘the science of reading’ is not an ideology, a philosophy, a political agenda, a one-size-fits-all approach, a program of instruction, or a specific component of instruction. It is the emerging consensus from many related disciplines, based on literally thousands of studies, supported by hundreds of millions of research dollars, conducted across the world in many languages. These studies have revealed a great deal about how we learn to read, what goes wrong when students don’t learn, and what kind of instruction is most likely to work the best for the most students.”

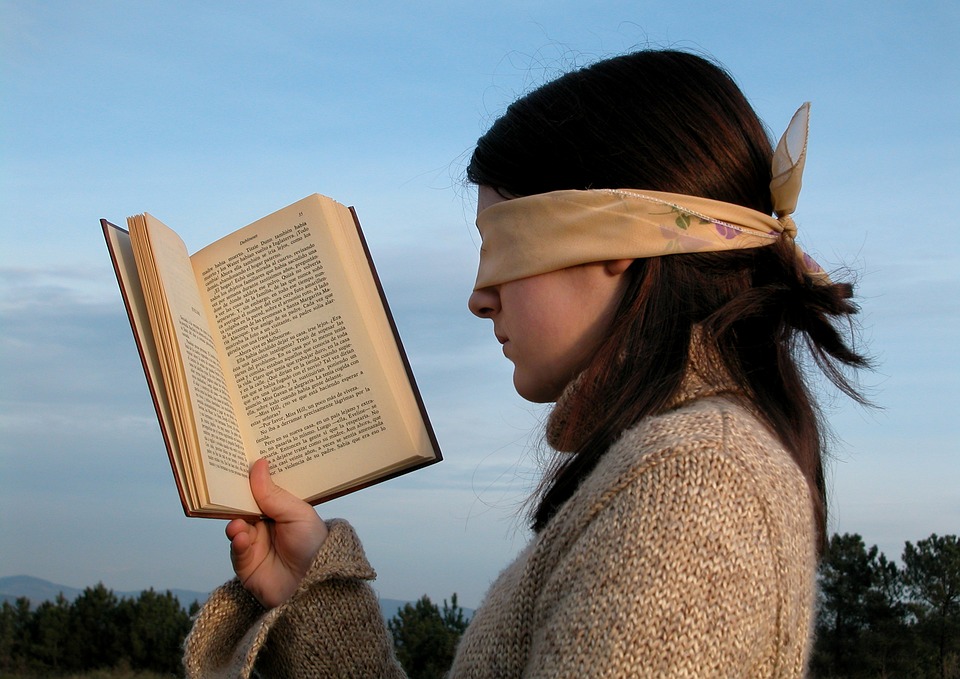

In contrast, with reading programs known as “balanced literacy,” students are only sporadically taught to parse out speech (phonemic awareness) and map sounds onto letters (phonics). This approach relies instead on a linguistic guessing game that urges students to look at pictures to figure out the word instead of teaching them to decode the letters. Balanced literacy, and its attendant low-literacy levels, is widely used throughout the state. California ranked behind 22 other states in fourth-grade reading scores in 2019.

Literacy improves when lawmakers and educators implement a scientific approach to reading instruction. Mississippi, for example — rarely thought of as an educational leader — fully embraced the “science of reading” eight years ago. It was the only state on the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress to improve its fourth-grade reading scores.

Santa Barbara Unified School District uses a balanced literacy program developed by education professor Lucy Calkins. A few years ago, in response to critical reviews, a token phonics component was added to the Calkins program, but it was too little and too late.

At least 20 states, including California, have passed, have pending or are considering laws requiring schools to teach the science of reading. Additionally, Denver, Seattle and Oakland districts, among others, no longer use the Calkins program. The dyslexic mayor of New York City and his schools chancellor are urging their principals to select reading programs other than Calkins’s.

Unfortunately, Santa Barbara, until recently, had not planned on adopting a new program until 2029. The district also will continue to train teachers in balanced literacy for the next three years.

Teacher training is key to improving reading performance. Inexplicably, most schools of education continue to teach prospective teachers balanced literacy, contrary to evidence that students learn better when their teachers are trained in the science of reading.

Research shows about half of students will learn to read under any system. It is the other half who are at risk for reading failure. Those students, including but not limited to English learners and socially and economically challenged children, need science-based instruction. Dismal reading test scores confirm this.

This is the situation in Santa Barbara and elsewhere. Currently (pre-pandemic as well), barely half of the students in its city schools read proficiently enough to meet the district’s standard. For English learners and other disadvantaged students, it’s barely a third.

Reading failure persists throughout a student’s life and can have severe social consequences. One telling metric, used to forecast future prison populations in California, is third-grade reading scores.

Will school leaders become better informed about the true cost of instructional practices they invest in and approve? Will superintendents and members of the boards of education in Santa Barbara and throughout the state be persuaded by a validated, peer-reviewed approach to literacy and change course? If not, how do they defend the status quo?

Ruth Green served on the State Board of Education from 2004-2008 and on the Santa Barbara Unified School District Board of Education. She is a member of the district’s Early Literacy Task Force.