It’s an old story: housing costs in our region are among the highest in the country. It’s a story we share with other desirable coastal communities. Demand is inevitably going to be high, and supply is inevitably constrained by limitations in natural resources like water, and by the need to protect the beauty — and the appeal — of this place.

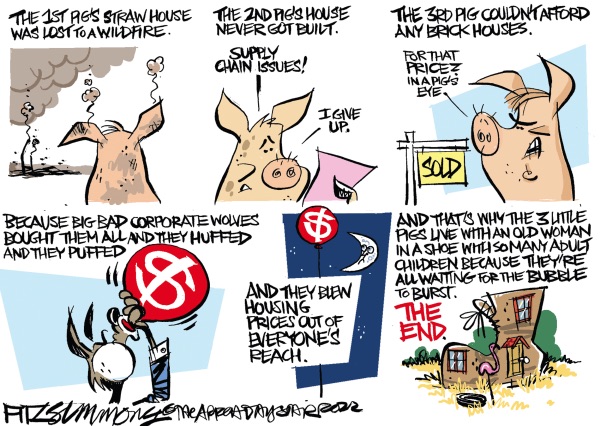

Now, however, we’re experiencing an unprecedented crisis of housing affordability. The real estate market is unprecedentedly “hot” — single-family homes selling above the asking, rental prices surging. Well-paid remote workers want to have a place here. Affluent retirees as well. Groups of students are able to share the rent costs; apartments are offered for vacation rentals. At the same time corporate investors seeking profit maximization are a major part of the landlord population. These trends, in the context of zero vacancy, mean that the private market cannot provide adequate housing at prices that the local workforce can afford.

Decades in the making, Santa Barbara’s housing affordability crisis has been significantly exacerbated since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which sent home prices soaring from already out-of-reach highs and brought no relief from rapidly rising rents. The median home sale price in the City of Santa Barbara rose an astonishing 30 percent in 2020-21 and an additional 34 percent in 2021-22 to reach $2.2 million. Already sky-high rents continued to rise, reaching an average of $2,400 per month, far outpacing household incomes that, following decades of stagnation for middle and lower-wage workers, have only recently begun to rise. With rents averaging above $2,000 throughout Santa Barbara and Ventura counties, commuting from elsewhere within the region is neither a viable nor an environmentally sustainable option.

The impact of these out-of-reach prices is felt most acutely in tenant households, in which housing costs absorb a growing proportion of monthly income. As highlighted in the Central Coast Regional Equity Study, recent Census data shows Santa Barbara to be one of the most rent-burdened — and least affordable — metro areas in the nation given the large proportion of households paying more than 30 percent, and considerable numbers paying more than 50 percent, of monthly income in rent. Communities of color have been disproportionately affected by these burdens, experiencing higher rates of overcrowding, eviction, and substandard conditions than their white counterparts.

The future of our community requires a large-scale, multi-faceted program to increase the supply of affordable housing — a reality recognized in the latest cycles of the state-mandated Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) goals. The RHNA goals, which have expanded significantly since the last allocation cycle, tell us what we need to aim for over the next decade in expanding the availability of affordable housing.

Implementing a program for meeting affordable housing supply needs will take many years — and the financial and policy framework for such a program doesn’t yet exist. Forging that framework is a very important priority.

But some immediate measures to protect affordability and stability are possible. Rent stabilization — along with other tenant protections — are viable and necessary tools for alleviating the current crisis.

Reciting the mantra that “rent controls have never succeeded” prevents rational discussion of policy choices. That mantra is based in part on models of rent control that are no longer relevant. In California, state laws — the 1985 Ellis Act and the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act of 1995 — put legal limits on how communities can protect tenants and regulate rents. Importantly, Costa Hawkins provides that newly built rental housing — meaning within 15 years — is exempt from rent regulation and requires vacancy decontrol — permitting landlords to return legally vacated, rent-controlled apartments to market rates. Strict rent control is simply not legal in this state. Moreover, rent stabilization measures typically provide that landlords are entitled to a fair rate of return and set up means for landlords to seek rent increases to pay for needed capital improvements or maintenance.

In comprehensive and authoritative surveys of rent regulation in California and across the U.S., researchers from the University of Southern California, the University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, and the Washington, DC-based Urban Institute offer careful assessments of what well-designed and implemented rent stabilization measures can accomplish. Far from “never succeeding,” these and other studies report that rent stabilization helps to promote residential stability at the household and neighborhood level, keep rental housing costs in check, and reduce vulnerability to unjust eviction, among other worthy goals.

As Professor Manuel Pastor and associates at USC conclude:

While more research remains to be done, the evidence does suggest that the strident debate about rent regulations may be driven more by ideology and self-interest — on all sides — and that public policy would benefit from a more measured discussion. What this review of literature suggests to us is that rent regulations are one tool to deal with sharp upticks in rent. They have less deleterious effects than is often imagined — particularly if we are talking about more moderate rent stabilization measures — and they do seem to promote resident stability and can therefore help to slow the displacement dimension of gentrification.

A comprehensive report done at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Urban and Regional Affairs concludes that:

The empirical research indicates that rent regulations have been effective at achieving two of its primary goals: maintaining below-market rent levels and moderating price appreciation. Generally, places with stronger rent control programs have had more success preventing large price appreciation than weaker programs. There is widespread agreement in the empirical literature that rent regulation increases housing stability for tenants who live in regulated units

These and other reports make it clear that rent stabilization is not in itself a solution to the crisis of affordability — but that smart rent regulation can help people who work here to live here. And it provides a framework for enabling tenants to protect the habitability as well as affordability of their homes.

Rent regulation need not be financed out of existing budgets. Most cities with rent control pay for the program by assessing a small annual registration fee for every rental unit. Concern about the administrative cost of rent regulation is not in itself a warrant for refusing to undertake it.

In short, a smart program to promote rent stabilization is a necessary and feasible tool in the long term effort to serve the housing needs of the local workforce, and all who contribute to the health, vitality, and stability of our community.

Alice O’Connor is a professor of history and director of the Blum Center on Poverty, Inequality, and Democracy at UC Santa Barbara. Richard P. Appelbaum is Distinguished Professor Emeritus and former MacArthur Foundation Chair in Global and International Studies and Sociology at UCSB and currently a professor at Fielding Graduate University.