Vincent Van Gogh Showcase at Santa Barbara Museum of Art

Major Exhibit ‘Through Vincent’s Eyes: Van Gogh and His Sources’ Tracks the Artist and His Influences

By Charles Donelan | February 24, 2022

When the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA) opens its doors on the new exhibition Through Vincent’s Eyes: Van Gogh and His Sources, the axis on which the art world spins will shift a little. That’s because wherever Van Gogh goes, the eyes of the largest audience that ever existed for a painter follow him. Whether it’s the astonishing prices his paintings now earn at auction or the widespread availability of reproductions of his most famous works, the public fascination with this artist seems only to increase with time.

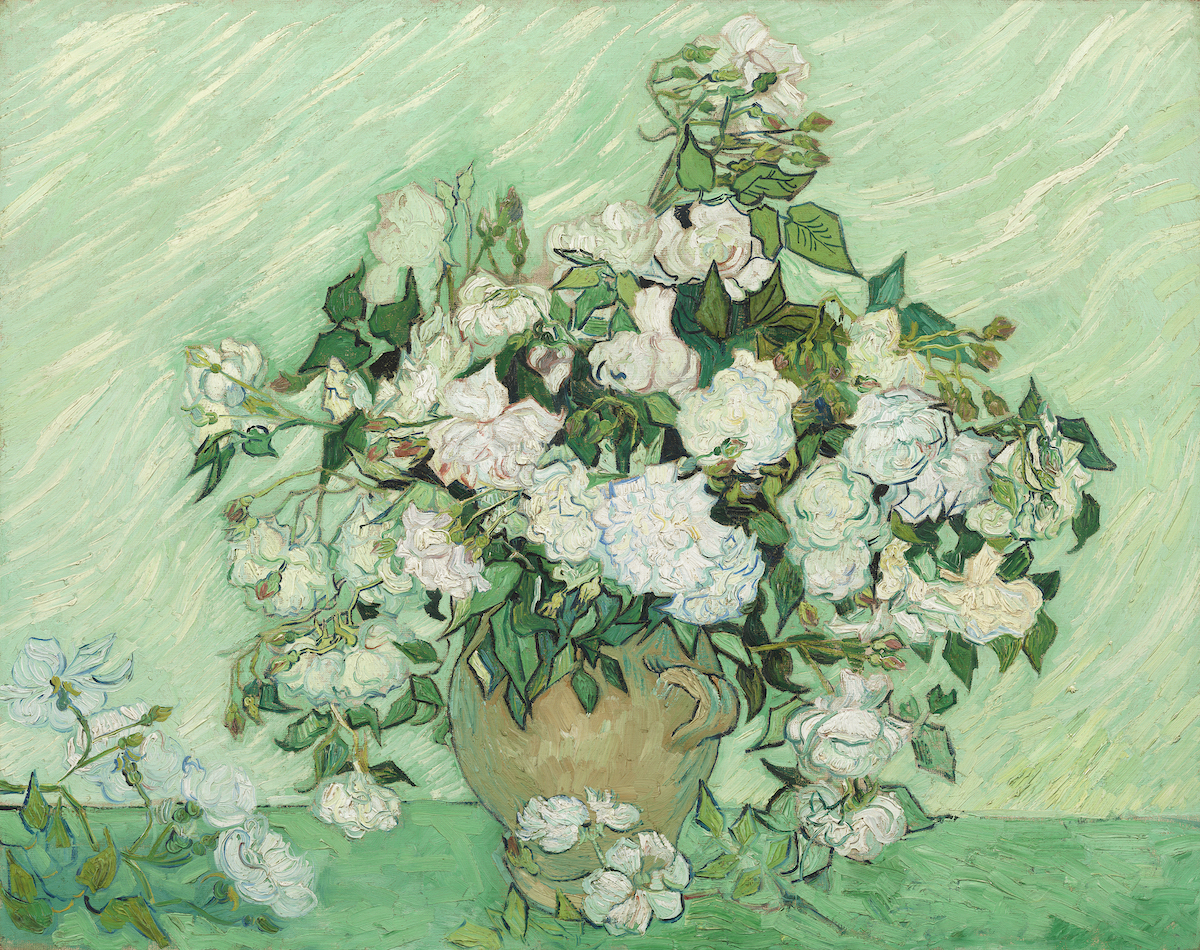

Yet as is suggested by the title Through Vincent’s Eyes, the exhibition that SBMA has mounted, which includes 20 works by Van Gogh alongside 75 objects selected to reflect the artists and writers he most admired, stands at some distance from the crowded Van Gogh marketplace.

Why are we getting this particular Van Gogh show? In Los Angeles, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and many more cities, people are lining up to enter a random space and view projected images of the artist’s work for an experience characterized as “immersive.”

Why, instead, did the curators at the SBMA work for years to bring together a substantial number of actual paintings by Van Gogh with dozens of examples of works that he studied and cherished while he was alive? The short answer is we are more intelligent.

Deliberate or not, the Through Vincent’s Eyes exhibit represents serious art history pushing back against the tide of commercialization and merchandising that has engulfed Van Gogh in the 21st century. Through Vincent’s Eyes gambles that the people of Santa Barbara want a historically informed presentation of Van Gogh’s art. They are ready to see his work through the lens of the visual culture he experienced. Rather than seeing his work projected 40 feet high in digital reproduction, visitors to Through Vincent’s Eyes will see what it might have been like to see the world from his perspective.

The Scale of the Project

Thanks in part to COVID, but primarily due to the complexities involved in borrowing all the works necessary to hang this show, Through Vincent’s Eyes has been years in the making.

SBMA Chief Curator and Assistant Director Eik Kahng described the process of putting together an international loan show as painstaking because “frequently, the loaning institution will send a courier with the object, and the courier has to physically watch you uncrate the painting.” They observe whether or not the condition you reported on arrival matches the condition they reported when the item was shipped, and then they have to watch you install it. The museum’s new loading dock and storage facilities have helped expedite the process. Still, inevitably with objects as valuable as Van Gogh paintings, which routinely fetch prices in the mid-eight figures at auction, there are unusual precautions in place. For example, even if they are shipping along the same route, you can’t put two of them in the same shipment — the exposure would be uninsurable.

On the day I visited the galleries last week, the installation team was busy working with a courier sent to document the hanging of a precious piece. In addition to the museum staff handling the painting’s placement on the wall, there were several other people whose role was to live-stream the installation process using an iPhone on a tripod so that the owner institution could monitor the work. I have seen a fair number of high-stakes exhibitions installed, but this was a first.

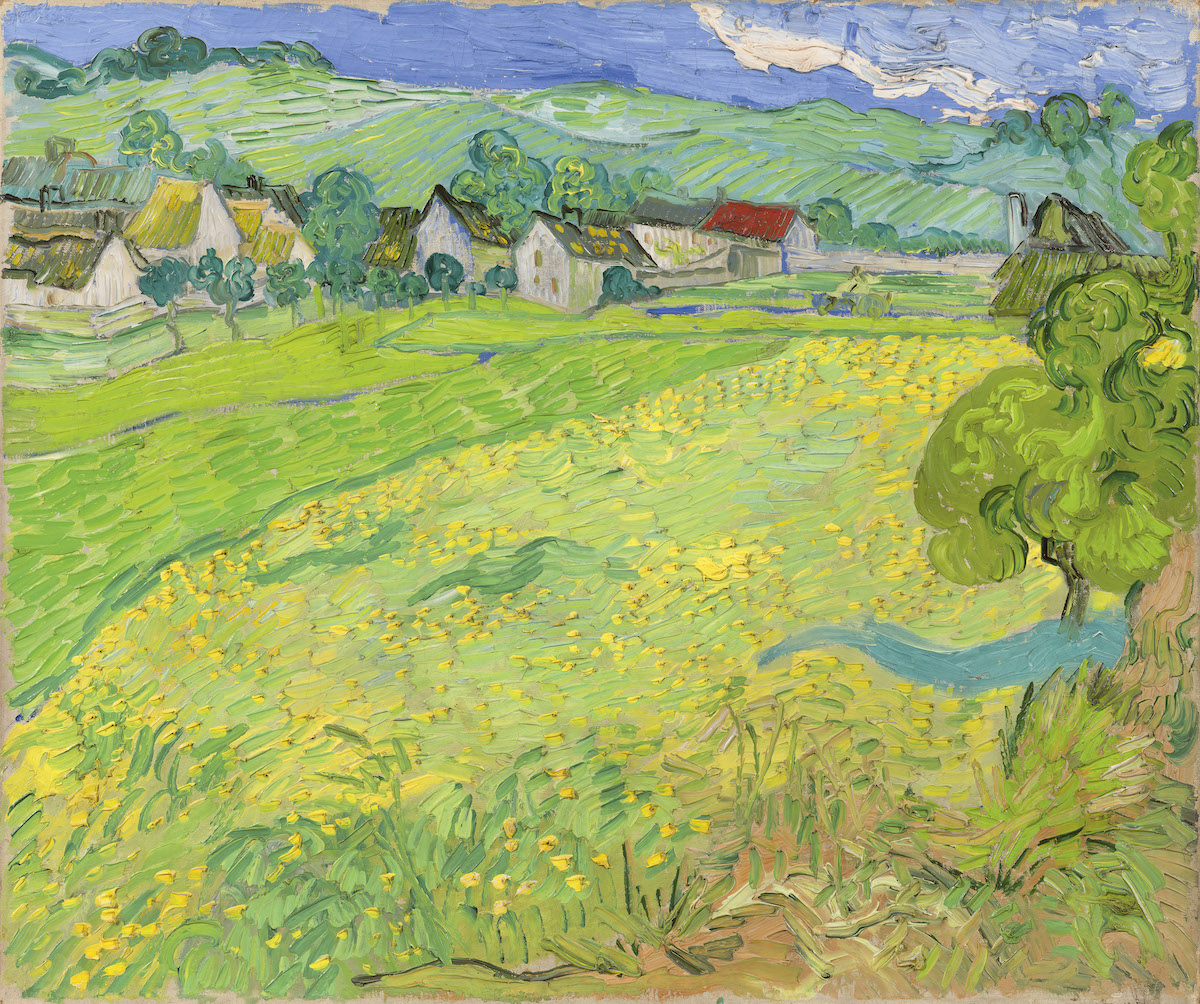

The good news is that visitors will experience a thoroughly unprecedented volume of influential art. In the gallery where the influence of Japanese printmaking on Van Gogh’s art is the subject, two of his most important works, the “Hospital at Saint-Rémy” of October 1889 and “Sheaves of Wheat” from 1890, hang side by side. The impact defies facile description. It would be hard to find a more impressive juxtaposition in any major museum in the world. Seeing the “Sheaves,” which is horizontal in orientation and light in color, next to the “Hospital,” which features a vertical vision of large trees rendered with the psychedelic arabesques of the artist’s late style, offers an unmatchable opportunity to experience Van Gogh at his aesthetic peak.

The World as He Saw It

Five essays in the sumptuous catalog that accompanies the exhibition examine the various contexts that informed Van Gogh’s project as an artist. Despite his outstanding productivity — more than 900 works — Van Gogh’s career was remarkably truncated. In just one decade, he progressed from copying drawings from books and prints to producing some of the most influential paintings in history. The emphasis in Van Gogh scholarship, and even more so in the popular imagination, has ordinarily been biographical. We tend to know him through the legendary dramatics of a few oft-told episodes, such as when he cut off his ear. As curator Kahng remarked to me, “The ear thing is the biggest cliché ever.”

Through this exhibit’s context-centered approach, we can begin to separate the man from the mythology and the work from an exaggerated emphasis on the perception of personal tragedy and possible madness that is supposed to have produced it. While his style is unquestionably distinctive, Van Gogh’s intention was not necessarily to be different from other artists or to work in a way that rejected the past. In “Van Gogh’s Realism,” art historian Marnin Young locates Van Gogh in relation to artists such as Millet and Raffaëlli, whose work represents the goals of Realism or Naturalism, rather than those of the Impressionists or the later avant-garde.

The interpretation of Van Gogh as a Realist is at the heart of this exhibition. To quote Kahng, Van Gogh was “not an artist who is just like a German Expressionist, trying to create these sort of wild, fantastic images of the emotions or something.”

Van Gogh, the voracious reader of novels, is the subject of another catalog essay, “Van Gogh’s Literary Imagination” by Rebecca Rainof. By looking through his eyes, we can see how his intention resembles that of his literary contemporaries George Eliot and Charles Dickens. Kahng defines this Realist strain in Van Gogh as analogous to that of those 19th-century writers as “wanting to engender and foster a sympathetic relationship with those who are underprivileged…. It’s a zeal for humanity and a true sense of emotional identification with other people. That is the goal of his art.”

Unlike the Impressionists that followed him, Van Gogh did not seek out the bright lights of the urban center. When he painted Paris, the relatively barren outskirts of the city attracted him, not the gleaming cafés and modern boulevards of the flâneurs. The isolated pedestrians depicted in “The Outskirts of Paris” from autumn 1886 and “Road to the Outskirts of Paris” from May-June of 1887 have nothing to do with Manet’s barmaids or the can-can dancers of Toulouse-Lautrec. Nevertheless, one does get a strong sense of how rapidly Van Gogh’s style was changing through the contrast between these two pieces. In a matter of a few months, the autumn painting’s muddy foreground and low gray clouds give way to the pointillist sunshine, and yellow blossoms of spring in the picture completed the next June.

Print Culture and Technique

While Van Gogh was absorbing ideas from prints and periodicals, he developed a pair of tools that had a profound impact on his final phase. The reed pen with which he drew influenced the distinctive rhythmic mark-making that would become his signature. The perspective frame mounted on long legs allowed him to operate en plein air with the assistance of a horizontal window within which to compose his landscapes. These technical devices supported his transformation of the graphic principles he observed in printmaking into the basis for his distinctive mature style.

Curator Kahng describes his transition as beginning with his study of reproductive prints. “It’s a funny thing to say, because we think of him as being the greatest colorist of his moment, right? But in fact, he starts out with this really dark palette, and a lot of that is because what he’s mostly been looking at are black-and-white prints.” There were no photographs of paintings then, only prints and reproductions, so for a very long time, that dominated the way he thought.

Using a reed pen that works almost like a Japanese brush, Van Gogh scores his drawings, and eventually his paintings, with clusters of dashes and arabesques that combine to make up a personal visual shorthand. Unlike his contemporaries, the Pointillists and Impressionists, his marks are not intended to blend and vanish at some specific distance. Instead, they remain legible whether the viewer is close or further away. A push-pull, pulsating relationship between surface patterning and the illusion of depth begins to take over and eventually dominate his late masterpieces.

With its horizontal orientation, the perspective frame also contributes to the evolution of Van Gogh’s complicated relationship to a one-point perspective. Without getting too far into the theoretical weeds here, I’ll say that in a painting like “Sheaves of Wheat,” with its doublewide construction, Van Gogh provides the consolation to the viewer of a Renaissance religious painting. But the spiritual in his work relies on visual sensation to excite a feeling of reverence for the natural world.

Potential Oneness, or the Fusion of “Here” and “There”

Beyond the aura of name recognition or the real or imagined benefits of prestige to the museum and the city, Through Vincent’s Eyes represents an unusual opportunity for all of us in Santa Barbara to participate in the indefinable excitement that radiates from Van Gogh’s best work.

Reading the catalog, the wall texts, and the individual descriptions of the various pieces on display, and finally standing in front of the two incredible paintings from 1890, I was struck by how powerfully one may identify with Vincent Van Gogh. I think that simply through extended viewing, everyone can experience some of the thrill Van Gogh must have felt to suddenly produce a work that conveys such universal power — his breakthrough moment. Kahng writes about how Van Gogh achieved such escape velocity and the obligation she felt to include paintings from the final two years of the artist’s life when he moved from Paris to Arles: “If we don’t have Vincent from the last two years, people will probably feel disappointed. There are lots of Paris period works that are just not resolved. Some things work, and some things don’t. It’s fascinating, though, to see how quickly he discards them when he moves to Arles. It’s like the jet just took off, and suddenly, you’re at light speed. Whereas before, you were plodding along and feeling your way through, but not absolutely sure what you were doing.”

Light speed. This metaphor is one way of talking about the thing that makes Through Vincent’s Eyes a must-see, once-in-a-lifetime experience for every kind of art lover. The best Van Gogh paintings compress one’s understanding of the painting “here” and the subject “there” in a potential oneness. It’s a paradox.

By putting ourselves in Van Gogh’s place, by reading what he read, and by looking at the art he admired, it’s possible to imagine for a moment not so much how he felt — that’s out of reach — but to see what Vincent saw, and see it in some semblance of the spirit with which he beheld it. That’s the potential oneness of art, and it’s here until the end of May.

You must be logged in to post a comment.