Members of UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Sociology are speaking out after hearing that undergrads from the school’s Gaucho Underground Scholars Initiative were denied admission into the Graduate Department of Sociology, throwing a wrench in the future for formerly incarcerated students on campus.

The program’s founding members fought tooth and nail over the past three years to build the Underground Scholars from the ground up, modeling it after similar programs at UC Berkeley and several other UC campuses.

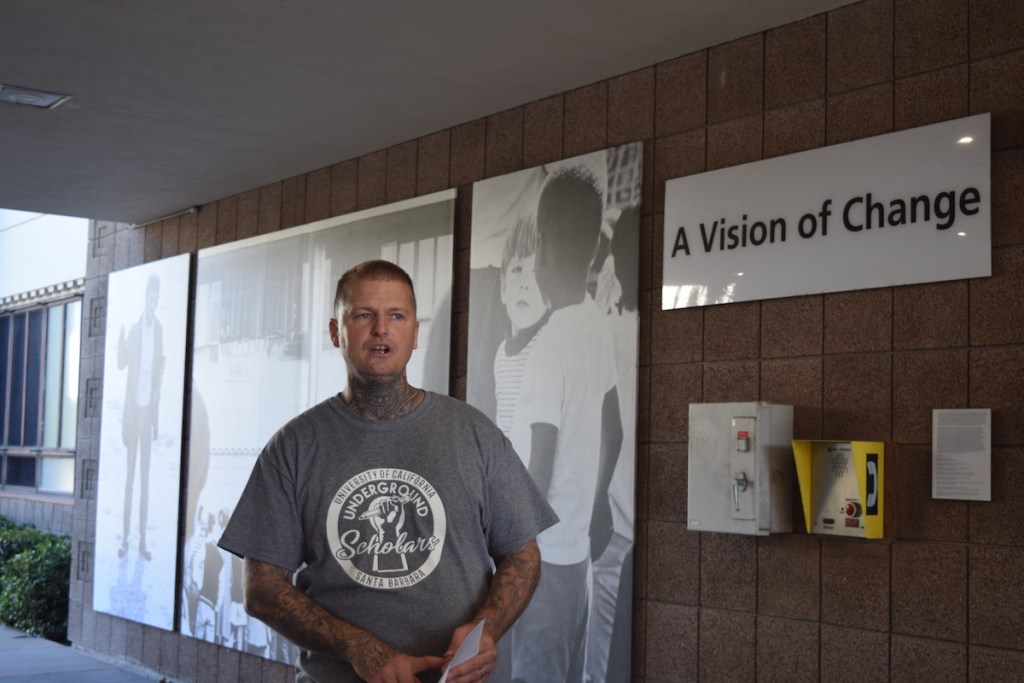

The bulk of the program’s working staff — including program coordinator Ryan Rising and advocacy coordinator Gilberto Murillo — applied to UCSB’s graduate sociology program, hoping to stay on campus and continue their studies while maintaining the day-to-day activities for the Underground Scholars. When they learned that their applications were all denied, they said it felt like the ground was pulled from beneath them.

“This is going to impact the Gaucho Underground Scholars for years to come,” Rising said. With seven of the eight core members set to graduate this fall, and the other set to graduate next year, the group is worried that the small sector of campus they built for formerly incarcerated students would be in imminent danger. “I think they’re using this denial as a way to get us out of here,” Rising said.

Rising and Murillo reached out to the graduate dean and other administrators, pleading for a chance for their cases to be reviewed. Both have nearly perfect transcripts, and both were hoping to use their unique backgrounds and life experiences to contribute to research that would reduce the effects of mass incarceration on American society. They were qualified, they argued, and their backgrounds would further the diversity of the graduate sociology cohort.

They weren’t alone in voicing their concerns — a group of about 30 members of UCSB’s Department of Sociology wrote and signed a petition, challenging the diversity of graduate admissions and the lack of transparency. “If the University of California is serious about reversing the harmful effects of mass incarceration,” the petition states, “it has an obligation to make higher education, including graduate programs, accessible to formerly-incarcerated and system-impacted students.”

The petition, written with the help of current PhD students in the Department of Sociology, asked that the graduate department reopen the students’ applications and consider accepting at least one member of the Underground Scholars to keep the program afloat for formerly incarcerated students on campus. “We believe that failure to admit these students constitutes a loss for the UCSB community as a whole,” the petition said.

One of the graduate students to sign the petition was Oscar Soto, the university’s only formerly incarcerated student in the department. When he first arrived on campus, like most students from a similar background, he felt out of place. It wasn’t until he met Rising and the Underground Scholars that he began to feel welcome at UCSB.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

Soto said that even within his graduate cohort, sometimes he feels singled out. “It feels like it’s me against the sociology department,” he said. He had to fight to earn academic credibility, he said, and felt like he was judged based on his looks or his past. “It was very isolating,” he said.

With another cohort set to join the department next year, and no formerly incarcerated students in that group, Soto worries that the resources that were available will slowly fade away without someone there to stand up for them. “Now that they’re being pushed out, who will be there for us?”

Rising said he was worried that the administration would take over a program built by formerly incarcerated students and replace it with staff who do not have the life experience necessary to connect with the often marginalized group. When he chose UCSB over UC Berkeley in 2019, he said that it was because he saw there was nothing for these students on campus and he wanted to be part of changing that. It was hard work, and he found it hard to feel accepted by the university. Almost all of the program’s funding, more than a million dollars, came from outside grants. Even his position as program coordinator was specifically named as a “student” position, while almost every other UC has hired a full-time director.

He was invited to sit in on a faculty meeting about the petition and the applications, though he said they only let him in for the last 15 minutes. The decision was already final: the department would not re-open any applications.

Leila Rupp, the interim graduate dean, said that the meeting itself was the university’s response to the petition. “The leadership of the department made clear that graduate admissions could not be reopened in fairness to all of the students who had applied, and that department members could not discuss the cases of individual students.”

She met with members of the Underground Scholars in the week before the meeting. It was then that she learned seven of the eight members were graduating and hoping to remain in graduate programs. By then the university’s hands were tied. The department claims that out of a pool of 140 applicants, only 10 were chosen — one of the most competitive selection processes in its history. But members of the faculty conceded that the graduate admissions had flaws, those flaws were highlighted by this specific incident, and they would need to be adjusted in the future.

Rising still hopes to be a part of that future, in any capacity. He also applied at UC Irvine, UC Los Angeles, UC Santa Cruz, and Harvard. He is hoping to earn his doctorate and return to Santa Barbara to advocate for formerly incarcerated students, if there is a spot for him.

“We may have lost the battle,” he said, “but let’s go get these PhDs and win the war here.”

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.