California’s Black History Started Here in Santa Barbara

Today’s Descendants Living on Gaviota Ranch Are Proud of Melting-Pot Ancestry

During February’s annual celebration of African Americans’ many achievements throughout the United States, it is interesting to recall the legacy of one of the first two Black men in California, who played a central role in the formation of Santa Barbara three centuries ago.

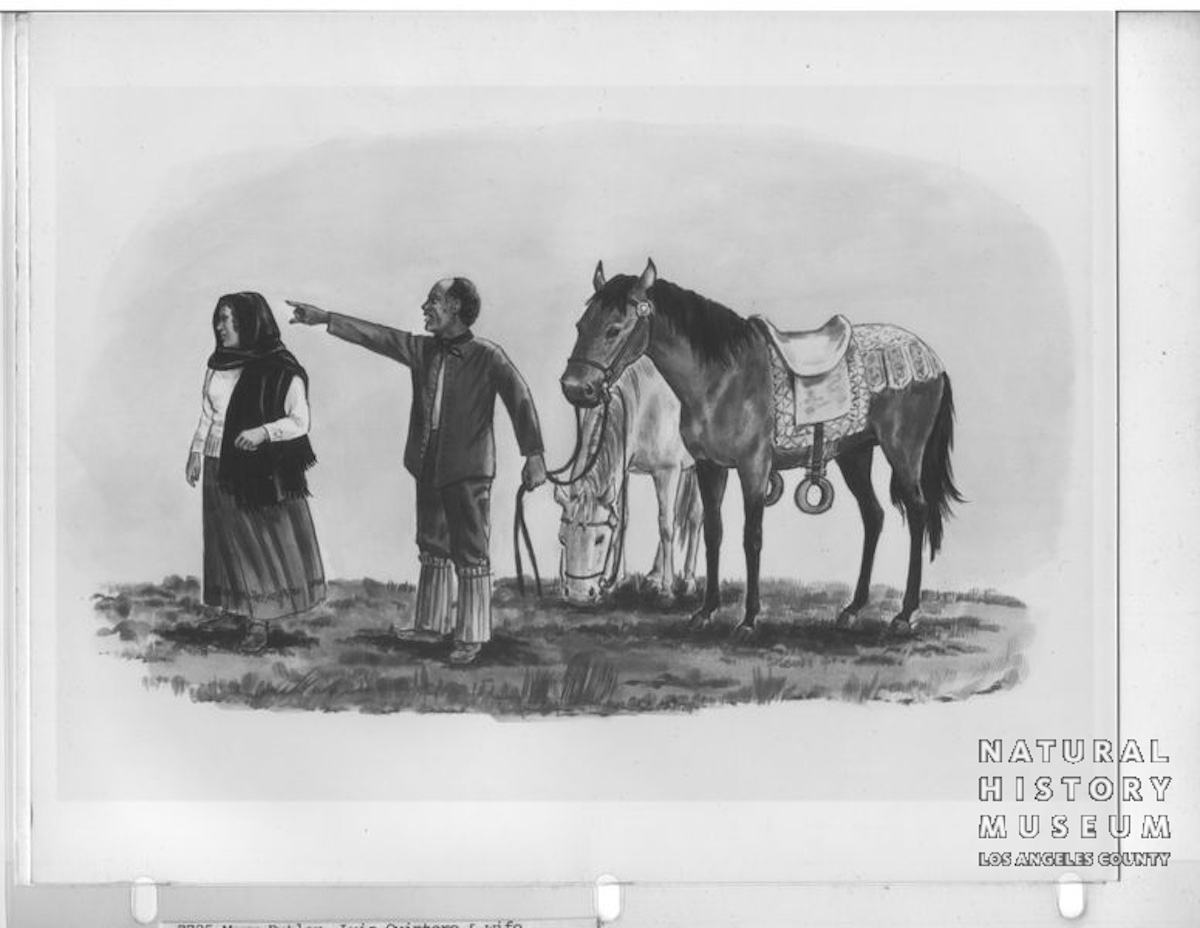

Luis Manuel Quintero, born in Guadalajara in about 1725, was a descendant of African slaves brought to Mexico, some as early as the 1500s. His wife, María Petra Rubio, possessed mixed ethnicities, including African as well as Indigenous progenitors from the coastal plains between the Yaqui and Sinaloa rivers.

The Quinteros and their children walked for six months — almost 1,000 miles — with the Rivera expedition from Sonora, Mexico, to Mission San Gabriel in 1781. They were among the original 11 families that founded the pueblo of Los Angeles that year. In 1782, they left Los Angeles and walked north to Santa Barbara when the presidio was established. Several of the Quinteros’ daughters married presidio soldiers.

Luis served as Santa Barbara’s first sastre (tailor), sewing uniforms from the cloth material requisitioned for the soldiers. He died in 1810 and was interred at Mission Santa Barbara.

Within only a few generations, the Quinteros’ African and Indigenous heritage continued through large families of descendants named Fernandez, Rodriguez, Valdez, Gonzales, Valenzuela, Pacheco, Flores, Cordero, Sepulveda, Lugo, Ortega, Romero, Garcia, Wilder, Smith, Goux, Chapman, Streeter, and others.

In 1838 the Quinteros’ granddaughter, Maria Rita Valdez, was granted Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas, which is now Beverly Hills. The name of today’s glamorous Rodeo Drive was extracted from the original ranch name.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

Valdez’s first cousin Rafael Gonzales, the Quinteros’ grandson, began serving as mayor of Santa Barbara in 1829. He later reported “there was little or nothing to do, because the size of the population was so small.” His adobe home, now a bookstore, still stands at 835 Laguna Street, a National Historic Landmark.

Rafael’s brother, Leandro Gonzales, served as mayordomo (administrator) of Mission Santa Barbara in the early 1840s. Chumash people referred to him as a “Black fellow — dark complexioned and good natured.” In 1837, the Gonzales brothers and several cousins were granted Rancho El Rio de Santa Clara in Ventura County. Oxnard’s Gonzales Road once led to the Gonzaleses’ adobe ranch house.

The legacy of California’s original African-American families lives on in the 10 or more generations that have passed since the Quinteros and three dozen other immigrants established Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. It is estimated that they have several thousand descendants in California today.

Quintero descendant Mark Tautrim, 74, is “quite proud” of his African-American ancestors and shares his appreciation for his family’s multicultural background with his two grandsons as they grow up on the same family ranch as he did, overlooking Refugio Beach.

Tautrim feels strongly about his family. “I want my kids and grandkids and on down from there to know that we are true ‘melting pot’ Americans and to be proud of our Black, Hispanic, European, and Native American ancestry,” he said. “Black History Month is especially gratifying and humbling, to know that Luis Quintero, my grandkids’ seventh-great-grandfather, contributed so much to California and Santa Barbara history.”

After graduating from UCSB, Nicholas Lorenzen, 29, went to work as an environmental technician at the local office of a nationwide consulting firm. Another Quintero scion, Lorenzen, appreciates his family’s legacy in Santa Barbara and California.

“It gives me a sense of place and responsibility to our community,” he recently observed, with evident pride.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.