Say So Long to Santa Barbara’s Offshore Platforms

Eight Rigs to Be Decommissioned in Next 10 Years

By Jean Yamamura

“Someone once asked me if a legal gambling den could be placed on a platform in federal waters,” said marine biologist Milton Love, laughing at the memory. It’s one of the ideas people may well now be considering.

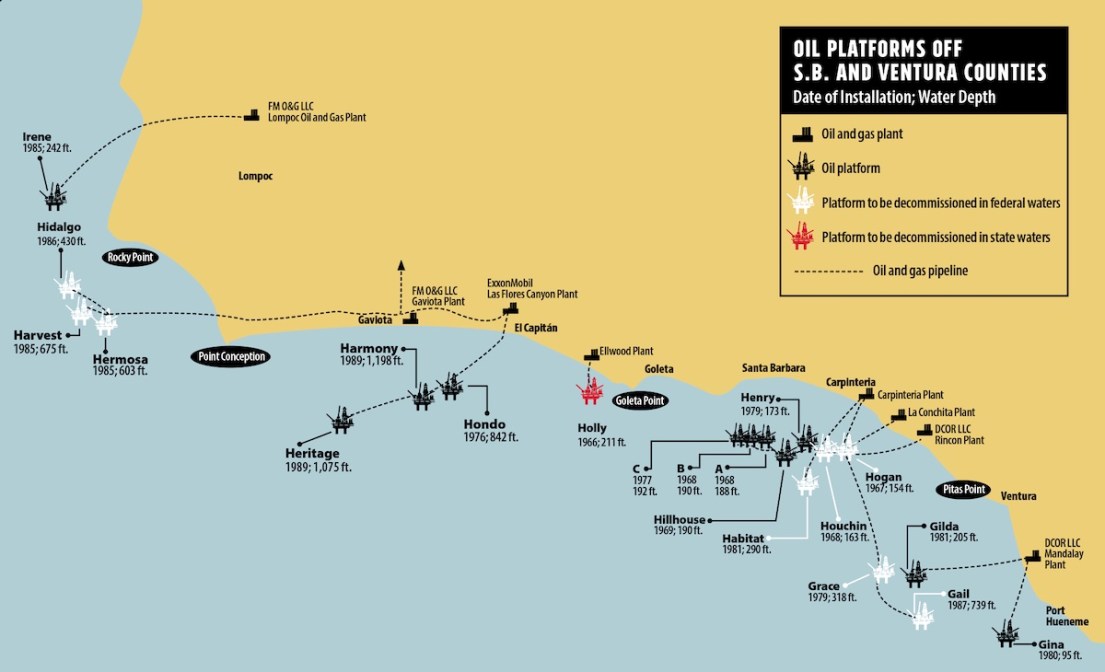

Eight oil platforms off the Santa Barbara coast are set to be decommissioned in the next 10 years as the first group among the 23 out-of-date platforms to be covered by a comprehensive decommissioning report the federal Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) will issue in February.

It seems miraculous that the coastal horizon may one day be clear of the platforms that have formed a familiar sight from Santa Barbara to Orange County for 50 years. Already, five of them are in the well-plugging stage or are about to be — Hidalgo, Harvest, and Hermosa off Point Conception, and Gail and Grace off Carpinteria; Houchin, Hogan, and Habitat near the county line round out the first “campaign” of removals.

Plugging the wells and removing the oil infrastructure at the platforms were an agreed-upon part of the leases, and the public gets to comment on the next phase, in which the fate of the platform structures and the pipelines and cables that connect them to shore is determined.

To that end, Love has been studying the sea life below the platforms for BSEE (pronounced “Bessie”), just the most recent work the expert on Pacific fishes has done during his 40 years based at UC Santa Barbara. Regarding the possibility of an oceanic casino, he speculated that helicopters could land at a platform when the wind cooperated, but the last time he went onto a platform, he said, he was hauled off a boat deck to a platform 200 feet above while holding tightly to the outside of a big net basket. “It was awful,” he said, especially for someone scared of heights.

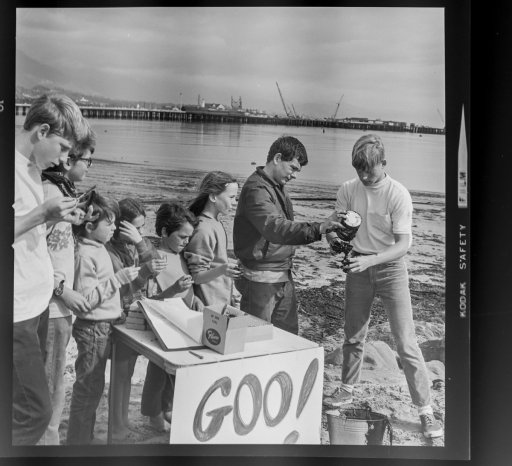

Get Oil Out!, commonly known as GOO!, has been fighting the platforms ever since the 1969 Union Oil Spill sparked a worldwide environmental conscience. “They agreed to take everything away, and they should take everything away,” said Carla Frisk, a boardmember with GOO! For once, the industry and activists may find themselves on the same side; Frisk understood that Chevron, which has responsibility for platforms Grace and Gail, prefers to get rid of the entire platform structure and the liability exposure if left in place. Chevron spokesperson Sara Dearman stated the company was assessing the decommissioning of its platforms and that no final decisions had yet been made.

The infamous Platform A that caused the 1969 spill still hulks off the coast and is scheduled to be removed in the second campaign of decommissioning. One platform, Irene off Lompoc, is still operating, and the third and last set of removals is the three ExxonMobil platforms — Heritage, Harmony, and Hondo — off Las Flores Canyon in Gaviota, also still active.

What rises above the water, however, is dwarfed by what lies below. Platform A straddles a relatively shallow 188-foot bottom; Platform Harmony sits above nearly 1,200 feet of water. Removing thousands of feet of inch-thick metal legs requires a special heavy-lift vessel, currently berthed in the Gulf of Mexico, where they sink cut-up platforms to form reefs. The removal program hopes to set a schedule that uses the vessel efficiently once it transits the Panama Canal, as well as the submersibles, divers, barges, experienced workers, and equipment necessary to cut a platform apart, load it onto a ship, and take it somewhere for disposal.

The current estimate, as of 2020, to remove the 23 platforms was $1.6 billion, though costs go up with every year that passes. The previous estimate by BSEE in 2016 was $200 million less.

If Platform Holly is any example, the passage of time is hard on ocean platforms. Holly lies in 211 feet of state waters, enduring constant corrosion and erosion from salt water, waves, and wind. The estimate to remove it is more than $350 million, a figure complicated by the fact that its last owner, Venoco, is bankrupt. That left the former owner, ExxonMobil, on the hook to pay the costs of removal. Venoco’s $22 million bond does not cover abandoning the wells it drilled, and California is bearing those costs, as well as the State Lands Commission’s oversight of the decommissioning process and the lawsuits that have resulted from the bankruptcy.

When State Lands took over the platform, it was in poor shape and had to be partially reconstructed and reequipped. Also, ExxonMobil’s assessment of the platform’s 30 wells found a third of them in an extremely poor condition to plug and the rest at an above-average level of difficulty and risk, said Sheri Pemberton, spokesperson for State Lands. Holly has yet to go through the state environmental process to determine the ultimate plan for the platform structure. If it is totally removed and disposed of and the sea floor restored, costs could reach $475 million, Pemberton estimated.

Some of the offshore leases go back to the 1940s, and the oldest of the existing rigs, Holly, was erected in 1966. (Platforms Hazel, Hilda, Hope, and Heidi were dynamited and removed in 1996.) The lifespan of an offshore oil platform is 35-40 years, said Miyoko Sakashita, senior counsel with the Centers for Biological Diversity, but their life contractually lasts as long as the oil field remains productive. “The thing that concerns us greatly,” she said, “is that operators will continue to pump out dribbles of oil to the last minute until they’re bankrupt.” She agreed with Frisk in preferring a complete decommissioning, “so that pipelines wouldn’t continue to drizzle contaminants into the environment.”

For Milton Love, who has spent countless hours underwater identifying the species living on the platforms’ legs, well casings, and diagonal bracings, it’s unthinkable to destroy what have become manmade reefs over the past half century. “They’re just covered in invertebrates,” he said with awe, describing the tight communities of sea stars, anemones, and sponges that extend to the deepest depths. “This is an amazingly cool place from a biological perspective,” he said, giving as an example how the male Garibaldi fish will remove all but the red algae growing on a support to build a nest to attract a female.

Love is no fan of the oil industry and the global warming effects it’s caused, but he appreciates the platforms: “These platforms are habitat for millions of animals. My opinion is that it’s immoral to kill huge numbers of animals in any kind of habitat.”

A complete removal of the platforms and their sea creatures is among the choices in the Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement, which will have a 45-day comment period. Another option is to chop the platforms off 85 feet down; the third is to do nothing. It’s a sure bet what GOO!’s position will be, as it has been unchanging since 1969.

“We know all the platforms are coming due,” Frisk said of their estimated lifetimes, “and the economic production of oil is just about gone, too. I do think they’ll be gone, and GOO! will be in favor of their complete removal.”

Click here to read the other stories in our cover package, “Is Big Oil Dead in Santa Barbara?”

You must be logged in to post a comment.