Belinda Rathbone’s ‘George Rickey: A Life in Balance’ Captures the Late Artist’s Local Impact

New Biography of Kinetic Sculptor Who Inspired Many in Santa Barbara

Many of you will remember the 14-foot stainless-steel sculpture that stood on the State Street steps of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art on and off beginning in 1999 and continuously from October 2007 until August 2017. It looked like an exploded palm tree constructed with parts from a jet aircraft. As the shining brushed-metal surfaces of its long, angular blades oscillated in the breeze, George Rickey’s “Six Random Lines Excentric III” radiated silent, Zen-like strength. At UCSB, in the space between the Art, Design & Architecture Museum and the lagoon, another large stainless-steel sculpture by Rickey, “Annular Eclipse VI,” is still on view. It moves with a similar smooth authority, its lofty steel circles intersecting and overlapping in graceful, uncanny patterns, throwing circular shadows on the scene below.

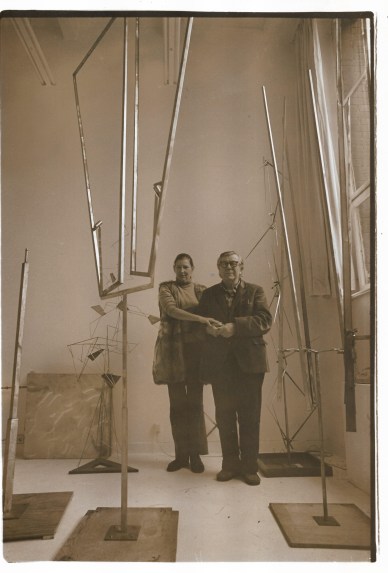

These spare, abstract works of art do not, at least on first glance, offer much in the way of personal information about their creator. Yet for those who had the good fortune to know George Rickey and his wife, Edie, they evoke many great memories of this charismatic couple. As frequent guests of the Dole and Cavat families, the Rickeys spent a significant amount of time in Santa Barbara from the 1960s through the 1990s, forming friendships, creating art, and inspiring others to become artists. Now, thanks to Belinda Rathbone’s excellent new biography, George Rickey: A Life in Balance, and to an extensive two-part show in New York City organized by the Paul Kasmin Gallery, the rest of us have an unprecedented opportunity to learn more about this important and influential artist, and to appreciate the extraordinary international network that George and Edie Rickey cultivated.

Despite its worldwide acceptance by museums, corporations, and municipalities, the kinetic-sculpture movement in modern art remains somewhat neglected, at least in comparison to other tendencies that sprang up alongside it, including abstract expressionism, pop, and minimalism. Steeped in the history of art and fluent in the theoretical discourses of cubism, constructivism, and the Bauhaus, George Rickey brought the mindset of an engineer to the task of creating a new form of sculpture. As a member of the team that created rotating gun turrets for the B-29 bomber during World War II, Rickey realized he had an aptitude for solving puzzles related to mechanical movement, but he only switched from painting to making sculpture after he met his second wife, Edith Leighton, in New York City following the war.

Edie was 17 years younger than George, and, at six feet tall, was noticeably taller than her husband. With an outgoing personality, a vivid imagination, and a bohemian sense of style, she contrasted sharply with her more logical and deliberate spouse, but it was the meshing of these opposites that would spark his career. From the beginning of their relationship, Edie took control over their domestic and social lives, cooking thousands of memorable meals, often with little in the way of kitchen equipment, and entertaining a wide range of acquaintances with delightfully daring repartee. Like many wives of artists in the 1950s and 1960s, Edie worked tirelessly to advance her husband’s reputation, making connections with dealers, collectors, and other artists and keeping the couple’s busy social calendar.

George too made and kept many close friends, several of whom became faculty members at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He met the art historian Alfred Moir at Tulane when they were both teaching there, and he met legendary UCSB professor of art William Dole even earlier when Dole was an undergraduate at Olivet College, where Rickey had been his mentor while serving as an artist in residence. The Dole family would go on to become extraordinarily important in the lives of both George and Edie, offering shelter and companionship and introducing them to the vibrant Santa Barbara art scene of the 1960s and 1970s.

This edition of ON Culture was originally emailed to subscribers on August 13, 2024. To receive Leslie Dinaberg’s arts newsletter in your inbox on Fridays, sign up at independent.com/newsletters.

In 1985, the painter Irma Cavat invited George and Edie to live on her property in Hope Ranch. With the help of contractor Tom Bortolazzo, they converted a wing of Cavat’s home into their Santa Barbara “nest in the west,” a place that allowed them respite from the cold winters of East Chatham, New York, their principal home. Tom’s brother Ken, an aspiring sculptor in metal who was a lobster fisherman at the time, became one of George’s studio assistants, a gig that eventually led him to a successful career of his own. Three of Ken Bortolazzo’s impressive kinetic sculptures are on view right now at Sullivan Goss.

In September 1988, a contingent of Santa Barbarans flew east at Edie’s expense to work on a project involving the documentation of her extensive collection of unique clothing and jewelry. Edie met Hilary Dole Klein; her mother, Kate Dole; and photographer Richard Ross at the East Chatham compound dressed in a peapod costume hand-painted for her by Karina Cavat Katchadorian, who, along with Santa Barbara artist Marge Dunlap, had decorated the building Edie called her “maisonette.”

Santa Barbara was just one of the far-flung locations in which the Rickeys made an impact. Through a series of grants from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) program, they spent part of several crucial years in Berlin, where George flourished among a younger generation of European artists eager to explore the potential of kinetic art. Intensely curious about the culture and history of Europe since his youth in Scotland, George had been friends with Jean-Paul Sartre and had contributed to Sartre’s journal Les Temps Modernes when he was still in his thirties. Rickey’s piece for Sartre’s publication described the new way of living based on the automobile then being established in America and highlighted a distinctly Californian phenomenon, the four-leaf-clover highway interchange, as an example of revolutionary design.

When Ala Story, the director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art from 1952 to 1957, met the Rickeys in 1970, she was moved to organize a touring exhibition titled Constructivist Tendencies based on 84 works from their collection. The couple had assembled these objects while George was researching Constructivism: Origins and Evolution, the book he published in 1967. One can only imagine the excitement that this influx of cultural sophistication caused among similarly inclined Santa Barbara residents at that time. The attraction was clearly mutual, and also intergenerational, as Rickey’s son Stuart attended UCSB, where he studied filmmaking.

Rathbone’s marvelously readable biography succeeds in bringing the Rickeys and the world in which they lived into timely focus. Meticulously researched yet free of academic jargon, the book offers 21st-century readers a rare glimpse into a moment and a movement that’s overdue for fuller understanding and appreciation. With George Rickey’s work on display this month on Park Avenue and at the Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York, the time is ripe for those of us who have lived with his legacy here in Santa Barbara to learn more about the lives of George and Edie, and the balance between them, in life and in art.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.