Blankenship Stops Building, Blames Loan Crisis and Permit Process

Developer Quits Condos

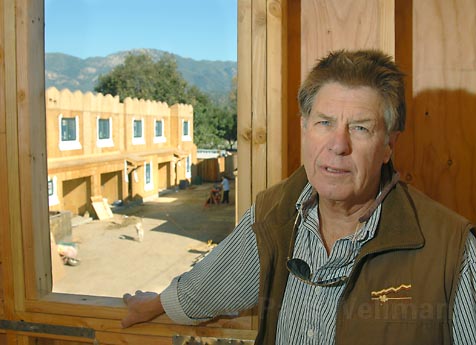

With some bitterness, condo developer John Blankenship declared to the City of Santa Barbara’s Planning Commission that he would not stand before them again. After 37 years in the business, Blankenship said that he was defeated not only by a declining market and the subprime loan crisis, but by a city permitting process that prevented him from profiting on his projects. It is the city’s loss, he added, because for the past couple of years Blankenship Construction has been one of the few still creating condos in the $600,000-$700,000 range-middle-class workforce housing, just like the city said it needs.

Blankenship said he has 29 such units scattered throughout the city that have gone through the entire permitting process but that he cannot afford to build, much less include the solar panels that he promised. He blamed the problem in large part on delays such as the “21 months and three redesigns” that staff had required for his four-unit condo project on San Andres Street, which was the subject before the Planning Commission when Blankenship delivered his speech on the afternoon of January 10. Costly delays; plus the $140,000 he had to spend on “sound studies, biological studies, archaeology and geology studies.” Blankenship particularly resented the fact that Councilmember Helene Schneider, on a “Touring with the Candidates” video during her recent campaign for re-election, posed in front of one of another Blankenship’s projects (though it wasn’t identified as such), a seven-unit complex at 1822 San Pascual,Street, the only workforce condos then under construction in the entire city. She said, “This is what we don’t need in Santa Barbara.”

Some of the project’s neighbors were on hand to object to Blankenship’s project at 1236 San Andres Street, adjacent to Bohnett Park, where four smallish condos would replace two 1920s redwood-framed craftsman bungalows. Immediately after the seven commissioners voted unanimously to approve Blankenship’s plans, he walked over to where the neighbors were sitting and said, “I’m not going to build it,” in a tone that was more accusatory than reassuring.

Just to be sure, the neighbors will now appeal to the City Council, though Blankenship and his wife, Hazel, continued to insist that they will not build, especially in light of the glut of low-end condos on the market in Santa Barbara: Currently 184 are comparable to those built by Blankenship. A few years ago these units were fetching up to $700,000; now they are going for $450,000. While city processes are not to blame for the slowdown in the housing market, said Hazel Blankenship, they are to blame for driving up such developer expenses as payment of the interest on the land loan to buy the property while waiting for the project to get approved. “It used to be worth it. An entitled property used to be worth money,” she said. In fact, the couple used to sell the properties after taking projects through the city process, as often as they would erect the building themselves.

Most of the buyers for their $600,000 condos were subprime borrowers, and although the last count shows a mere 41 homes in foreclosure in the City of Santa Barbara, compared to 450 in the Santa Maria and Lompoc area, the banks have stopped making those kinds of loans. Consequently nobody, said Hazel Blankenship, including herself and her husband, “has the nerve to try to build.”

Of course, not everybody mourns the fact that it is now a buyer’s housing market in Santa Barbara, following years of escalating prices. As for Schneider, she stood by her opposition to the seven-unit San Pascual project, which she criticized for its lack of internal gardens or other outdoor space, except for the driveways. “I don’t believe in cramming as many people as possible into as small a space as possible,” Schneider said.

It remains to be seen whether reduced housing prices will alleviate the disappearance of gardens, lead to an even more severe dearth of workforce housing, or both.