Cresco Proposes State-of-Art Carbon Scrubbers for Giant Pot Greenhouse in Carpinteria

Indoor Filtration System Could Prevent Fugitive Odors from Becoming a Neighborhood Nuisance

At the allegorical 11th hour and 59th minute, owners of a proposed new cannabis greenhouse in Carpinteria — about three-quarters the size of Santa Barbara’s Paseo Nuevo Mall — submitted last-minute new plans to install a state-of-the-art internal carbon filtration system to prevent fugitive pot odors from becoming a neighborhood nuisance.

This new indoor odor-control system would be in lieu of the outdoor air-misting system initially proposed — used by many greenhouse operations — which is designed to neutralize the smell of cannabis by changing the molecular structure of vapors “burped” from the greenhouse. This substitution came shortly before last Wednesday’s meeting of the Santa Barbara County Planning Commission. Commissioners voted to delay their vote until September 1 to give members of the public — not to mention county planning and legal staff — time to review the new proposal.

To the extent the battle over cannabis has been driven by odor complaints, this proposed new approach could prove to be a game changer. Industry critics throughout the Carpinteria Valley have long complained about cannabis odor intrusion and have insisted for almost as long that all greenhouses be equipped with carbon scrubbers, which reportedly capture the smell before it can escape outside. Until recently, the cannabis industry has argued back that most greenhouses are not structurally equipped to accommodate carbon scrubbers. Likewise, they have noted that Carpinteria lies at the tail end of the system for electrical deliveries and that that the demand for additional electricity imposed by carbon filtration systems could strain the grid’s carrying capacity.

None of those issues, however, seemed to daunt Cresco Labs, a Chicago-based cannabis conglomerate big enough to sell shares of stock on the Canadian Stock Exchange. Founded in 2013, Cresco now boasts 2,700 employees in 32 retail outlets and 18 production hubs located in 10 states throughout the country. Six of those production hubs are in California.

In 2018, Cresco partnered with the Van Wingerden family, mainstays of Carpinteria’s substantial greenhouse industry, then in the process of making a massive pivot from cut flowers to cannabis. The property in question — 13 acres by Foothill Road and Via Real and abutting Arroyo Paredon Creek — has been in agriculture since 1928.

But even by Carpinteria greenhouse standards, the Cresco proposal is undeniably big. Three existing greenhouses — built in the 1960s — will be demolished; in their place will be a modern greenhouse structure encompassing nearly 400,000 square feet. In addition, Cresco is proposing to build a processing plant nearly 41,000 square feet large. The number of workers anticipated to keep this new operation humming is 75, a three-fold increase from the 25 who work there now.

Since arriving, Cresco has hired a full-time community liaison worker who, the commissioners were told, has waged an aggressive listening campaign. The company has given generously to community charities and causes, spending $25,000 in local restaurants, a spokesperson said, to keep the food industry afloat in the time of COVID. David Gacom, a Cresco executive, expressed pride in the proposal and used words like “thoughtful,” “mindful,” and “intentional” to describe the company’s approach to achieving its “cutting-edge” stature.

They also had the good sense to hire land-use planner and engineering consultant Nathan Eady to act as their spokesperson. Eady is well-known to the planning commissioners from a host of other projects he has worked on; speaks with a gravelly, low voice; exudes an understated authority; doesn’t sell too hard; and has come to enjoy the commissioners’ trust.

Not everyone in Carpinteria is bothered by the odors, but those who are are really bothered. And very vocal. They also write a lot of emails, about 700 at last count. Most wanted the project just to go away. But failing that, they wanted carbon scrubbers, not the Byers vapor system that shoots a fine mist of unknown chemicals infused with a blend of essential oils into the atmosphere. This spray allegedly combines with airborne cannabis molecules to create entirely new compounds that do not register in the human nose or the human brain.

Industry critics have expressed keen skepticism that the Byers system works as advertised; at least two of the planning commissioners — Michael Cooney and John Parke — shared that skepticism and would not have voted for the project had the Byers system been the only odor-control system installed.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

In an interview after the meeting, Parke likened the smell of Byers’s mist to the smell he experienced getting sick while still in college after having imbibed one too many drinks that came adorned with paper umbrellas. Cooney said he has no independent experience of the misty smell but noted the persistent pungence of errant airborne cannabis molecules was plenty invasive enough.

Cresco, it seemed, got the message. “We really stretched ourselves,” said Eady, “and listened to the people.”

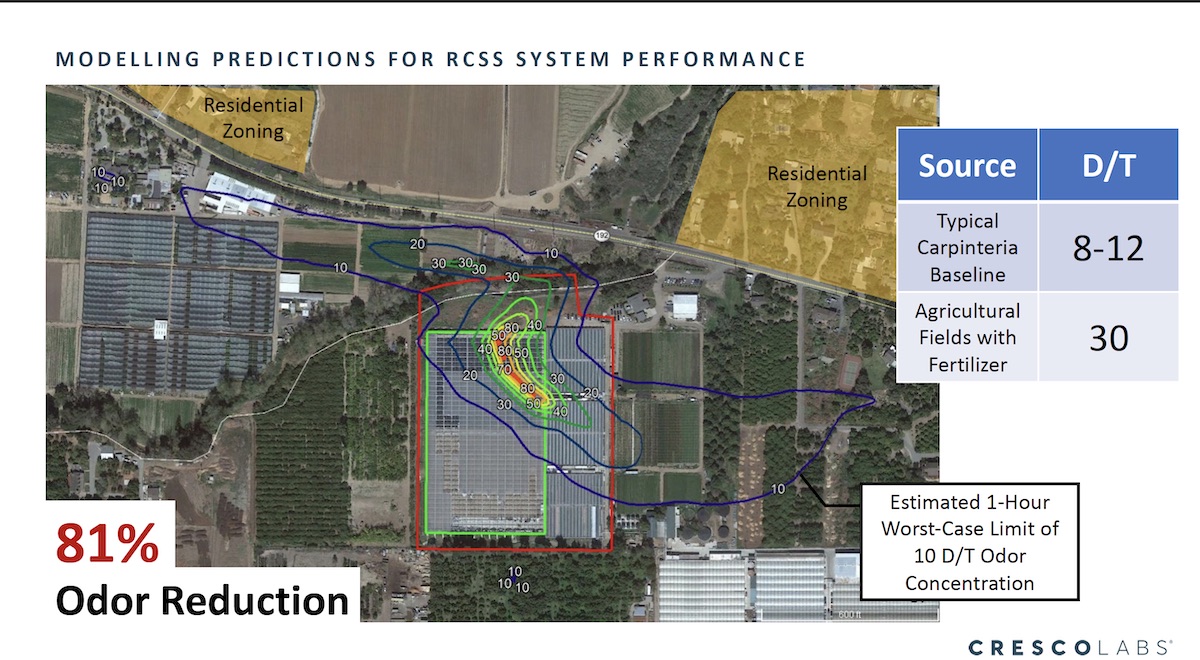

Translated into the science of odor control, in a worst-case scenario, Eady stated, the carbon scrubbers could reduce detectable emissions to the typical ambient levels found throughout Carpinteria. The worst one hour out of five years, he vowed, would be no worse than 8-12 D/T, or dilution/threshold, a metric used by the odor-control industry to quantify the very subjective experience of smell. A 30 is the measure ascribed to a typical farm field to which fertilizers had been applied.

“Eight to 12, that’s very low,” said Eady. “For an odor to be a nuisance, it has to be recognizable and persistent. One hour out of five years, I wouldn’t say that’s persistent.”

Eady said Cresco had hired a company from Holland to design the carbon filtration system to capture the cannabis odors before they can escape the greenhouse and production room. He said the present model is 81 percent effective in trapping the odors and that the remainder that gets out is dispersed by the prevailing winds and diluted before it can reach any nearby residence. He said he expected the next generation of design to be 87 percent effective. When ambient winds, topographical conditions, and meteorological patters are factored in, he said the new system would be 99.95 percent effective. “No system is 100 percent,” he cautioned.

By contrast, Eady said the Byers misting system was 97 percent effective. Until right before Wednesday’s hearing, that was the system Cresco and Eady were promoting. He claimed Byers worked based on 33 samples he had taken over a three-day period.

The carbon system, Eady added, would not be available for installation for 12 months. The Byers system would be used until then. Commissioner John Parke was eager that Cresco deploy both systems as “a one-two punch.” Eady said the intent was to discontinue Byers as soon as the carbon scrubbers demonstrated they were effective. He cautioned that if carbon scrubbers were used — trapping cannabis odors before they could escape — that the misting system could become an odor issue.

The vapor is known by the trade name Ecosorb and is the subject of concern by some Carpinteria residents who worry the unknown compounds might pose an environmental risk to the steelhead trout, the tidewater goby, and the red-legged frogs (all endangered species) that call the Arroyo Paredon Creek home. If more mist molecules are released than there are cannabis molecules, it would become detectable, he said.

Parke and Cooney have pushed the industry to do more to control escaping odors. Both expressed optimism that the carbon system might offer a significant improvement. Both have expressed frustration that more hasn’t been done sooner. Despite all the conditions of approval imposed on various cannabis projects, Cooney opined, the problem has persisted. Vows to enforce, he said, have floundered because odors can’t be tracked down to obvious sources.

“It’s like this: You arrive at a crime scene and everyone’s pointing to a different location as to where the gunshots are coming from,” Cooney explained. “But what you’ve got is a dead body. You know someone shot that person, but you don’t know who it is.”

The Cresco proposal is not the first greenhouse in Carpinteria to propose carbon scrubbers; it’s the second. It is, however, the biggest. By far. Parke was intrigued by the applicability of this technology to other greenhouses. “You know, what I’m looking for,” he told Eady at one point, “is all of it.”

Eady cautioned that the system proposed was designed for this specific site with site specific wind conditions and site-specific distances from the nearest neighbors. “It’s not a universal silver bullet for everybody,” he said.

The vote was pushed back to September 1; the outcome could well be a unanimous vote in favor. Parke had hoped the hearing could be held another day. He and his wife breed Great Pyrenees mountain dogs, and they have a litter due that day. He couldn’t make the first. When other commissioners pressed Parke to change his plans so he could participate in the vote, he resisted. “With dogs, you measure the due date from the day of ovulation. I can’t change that. I’ll be in there whelping puppies. You know my wife; she’s Corleone Sicilian. I won’t live another day if I miss that experience,” he said.

The other commissioners declined to budge; those attending the next meeting might witness Parke’s dog’s litter coming into the world. “They may learn a little more about the birds and the bees than they bargained for,” Parke said with a laugh.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.