Unmasking Isla Vista: University & Students

This story first appeared at The Daily Nexus.

[This article can be accessed as both a podcast and a KCSB newsletter. Please visit our landing page to learn more about this project].

Following the announcement of campus closure during Winter Quarter 2020, UC Santa Barbara — like all universities — began its journey of responding to the pandemic on multiple fronts, including academic dishonesty concerns, mental health among students and housing for first and second-year students. As the university calculated and executed its response, students grappled with the challenges the pandemic posed to learning and living as a UCSB student.

Academic Dishonesty

The remote learning environment — ushered in by the pandemic — brought forth a slew of new challenges for students, among them the issue of academic dishonesty.

The Office of Student Conduct (OSC) reported a “large increase in referrals for academic dishonesty,” as stated in a campus-wide email sent in January. According to the email, students “feel less connected to the learning community than they felt in person, and this feeling has created detachment from normal academic standards.”

Students who receive referrals undergo a hearing and trial process to determine if they have violated student code. The Office of the Student Advocate (OSA) helps to inform students of their rights throughout this process and aid them through the trials and hearings.

Geovany Lucero, the 2021-22 student advocate general and internal deputy chief of staff for OSA, said that the trend of cases involving academic integrity and dishonesty went up during the pandemic.

“We did have an overwhelming amount of cases regarding academic integrity and academic dishonesty. There was a lot of confusion [from students] … like, ‘What does this look like? What does this mean?’” Lucero said.

Much of the confusion occurred because students were not properly notified by the OSC on the processes of receiving a referral, according to Lucero, and the fear around receiving such a referral was only intensified by the isolation of the remote environment.

“Imagine getting an email as a first-year transfer, as a student who has never had to deal with this kind of thing before, especially with remote learning, and being told you have been reported to the Office of Student Conduct and you’ll have a hearing to see where your stance and enrollment as a student is,” Lucero said.

“And so on top of that, all you know is that you have a trial coming up, but you have no idea what to expect, you have no idea who’s gonna be there, you have no idea what to even argue,” Lucero said.

Various forms of academic dishonesty that students were referred for included collaborating on messaging apps like GroupMe, Discord and Snapchat during exams, or even switching between tabs during closed-note assessments on GauchoSpace.

Lucero noted that one form of academic dishonesty that came up frequently, and was largely unheard of by many students, was self-plagiarism — when students recycle language from their own previously submitted assignments. But in Lucero’s eyes, charges levied against students for self-plagiarism were too harsh, especially in light of remote learning, and they believe leniency should be given in some instances.

“In some specific cases, I don’t believe self-plagiarism should count as a negative thing … I think that students should be able to, especially in the nature of our academic year last year, [turn in assignments] that have a rendition of previous words [they have used],” Lucero said.

These charges of academic dishonesty have the potential to change the trajectory of a student’s path at the university, as their academic standing can shift due to disciplinary measures they may receive. The hearing and trial process exists to allow students to contest the charges before facing any disciplinary action, but Lucero said that some students who were accused of academic dishonesty in the past year faced disciplinary action before any hearing occurred.

“Our student Bill of Rights says that ‘All students accused of any dishonesty or any allegation against them are innocent until proven guilty,’ [but] many students in many of our cases were already suffering consequences and facing repercussions for these allegations,” they said.

Several students were automatically given an “F” grade for an assignment or dropped from their class entirely, placing them in poor bad academic standing before having any hearing, Lucero said.

“It was frustrating to see that a lot of students were facing the consequences, either without proper notice, or again, without that proper hearing and trial process that the university promises.”

The email sent by the OSC in January outlined this process, but Lucero wishes that the message had been sent earlier and suggested that sending that kind of message annually could be beneficial for students.

“[Educating students on the trial process] should have been done in the beginning of the school year,” they said. “Maybe this kind of stuff could have been prevented by highlighting or reminding students of this process.”

International Students

International students at UCSB were grappling with difficult choices and situations as a result of the pandemic, including deciding between returning to their homes outside the United States or staying in the country.

International Chinese student and 2021 UCSB graduate Tianyi Huang shared that being unable to go back home took a toll on her mental health.

“There is definitely a lot of distress and anxiety and depression around not being able to go back home, because this has been the longest time I stayed here without going back to China,” Huang said. “I feel pretty homesick, not being able to go back at least once a year. It definitely affects my mental health a lot, which affects my grades and my studies. It’s a lot and it affects my graduation plans and my future plans as well.”

International students on M-1 and F-1 visas also had to navigate the July 2020 announcement from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (I.C.E.) that international students who were not attending their fall 2020 academic term in person would be barred from residing in the U.S. Though the policy was later reversed, many international students faced complicated travel restrictions amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and fear of not being able to return to the U.S.

Though international students were ultimately allowed to stay in the U.S., Fall Quarter 2020 brought its own complications. Students who chose to return home outside the U.S. faced different time zones for classes and lectures, and those remaining in the U.S. experienced isolation and witnessed a rise in hate crimes against East Asian peoples.

Huang shared her experience living in the U.S. with witnessing some individuals committing hate crimes against East Asian peoples and blaming them for the COVID-19 pandemic.

“A lot of them do not happen face to face, just see some comments online that makes you feel sad. You can read the news about how Asian communities being attacked because of the pandemic and all the sentiments from the last U.S. president, ‘Kung Flu,’ that kind of thing. If you read those news online, read comments talking about this, you will just feel sad,” Huang said.

Navigating housing as an international student was quite strenuous, Huang said, but she credited the university for providing resources that helped her access housing and food supplies, like the Miramar Food Pantry.

The coming 2021-22 school year brings its own challenges for international students. According to fifth-year political science, sociology and environmental studies triple major and External Vice President for Statewide Affairs Esmeralda Quintero-Cubillan, “there has been increasing concern regarding the allocation of student visas, particularly to Chinese and Indian international students at UCSB.” Quintero-Cubillan said that the allocation issue extends UC-wide but is quite prominent at UCSB.

“For Indian international students, the concern is the ongoing COVID crisis and how that’s impacting the reopening of U.S. embassies in India and actually being able to process these international student visas,” Quintero-Cubillan said. “In addition, there’s the issue in which there’s not enough people to staff [embassies] at the moment because it is an ongoing COVID crisis as well as the massive backlog in terms of the processing of student visas.”

Quintero-Cubillan added that Chinese international students face the same trouble with embassy reopenings as Indian international students, in addition to grappling with Presidential Proclamation 10043 from former President Donald Trump, which disallows some Chinese graduate students and researchers from entering the U.S.

Current President Joe Biden has yet to reverse Trump’s policy.

Quintero-Cubillan added that she is currently addressing this issue by working with the UCSB Office of International Students and Scholars (OISS).

“[What] I’ve been doing is maintaining conversation with OISS, setting aside some of my budget, particularly to create and develop emergency grants for international students who may have trouble affording basic needs, as well as just processing their visas and the fees that may come along with that,” they said.

In addition, Quintero-Cubillan said that they are working with UCSB’s MultiCultural Center to sponsor “entertainment and enrichment programming for our international community” in order to provide a sense of belonging and community.

Mental Health

Living in isolated environments both in I.V. and their hometowns, students faced mental health challenges in juggling the demands of being college students with the pressures posed by the pandemic.

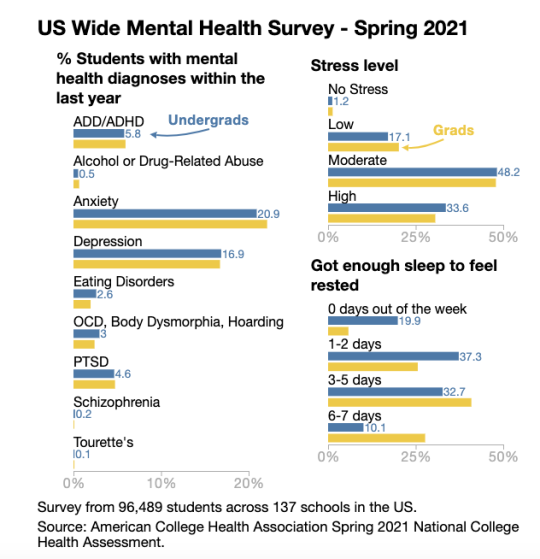

The American College Health Association Spring 2021 National College Health Assessment revealed the following trends about the mental health of college students over the past year.

At UCSB, Walid Afifi, a professor in the communication department, said that he tried to “take a humanistic approach to being a professor while simultaneously maintaining rigor” because “students, everyone, we all need to feel supported.”

Walid Afifi and Tamara Afifi, communication department chair and professor, conducted a national survey together to investigate the COVID-19 pandemic’s consequences on the population’s mental health and well-being.

“It is jarring in some ways, the extent to which socioeconomic status really impacted uncertainty,” Walid Afifi said. “Everyone was affected [by the pandemic], but it depends on your story, your starting point … If your beginning level of stress and uncertainty is low, you might be able to take that increased hit a little better because you have the resources and you’re not constantly trying to manage it throughout your life.”

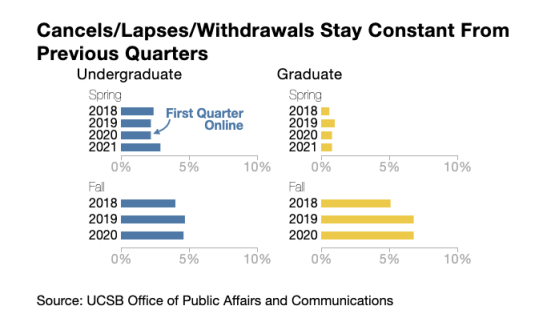

Despite the extensive impact on the UCSB community’s mental health, the drop-out rate stayed constant during Spring and Fall Quarter 2019 and Spring and Fall Quarter 2020. Spring and Fall Quarter 2020 were the first two fully-remote quarters.

Housing

University housing arrangements have been uncertain due to changing COVID-19 guidelines from the state and the Santa Barbara County Public Health Department.

The university originally limited fall quarter undergraduate housing in August 2020, only accommodating those with “special circumstances.” Only Guardian Scholars — students in the foster care system — and unaccompanied houseless youth fell under this classification. These students were offered housing at the San Clemente Villages graduate apartments.

Such modifications to UCSB’s usual housing policies fell severely on resident assistants (RAs) in the fall, with UCSB RA applicants being told a month before the beginning of fall quarter that their employment would be suspended during the 2020-21 school year.

In response, the UCSB RA Coalition demanded housing and benefits through a Change.org petition that had 941 signatures as of Oct. 5, 2020. As a result, UCSB sent 23 RAs offers for Winter Quarter 2021, though 40% of these accepted applicants announced the deferment of their appointments until the 2021-22 school year. The main frustration stemmed from the short notice of their employment suspension and having to find alternative housing quickly.

Following UCSB’s decision to provide limited housing for Winter Quarter 2020, 1,000 undergraduate students with special circumstances moved into university-owned apartment complexes in I.V., such as Sierra Madre Villages and Santa Ynez. The university adjusted housing to accommodate for COVID-19 mitigation efforts by altering rooming arrangements and sanitizing the rooms prior to move-in dates.

Now, with Fall Quarter 2021 approaching, Chancellor Henry T. Yang announced on June 11 that the university plans to open housing at full capacity and will continue to monitor public health guidelines for any possible changes.

According to Quintero-Cubillan, many students relying on the university for housing are on waitlists and uncertain about their living situations for the upcoming quarter. Most students living in I.V. signed leases months ago, which could lead to students scrambling for housing if they aren’t offered a contract.

“There’s an upcoming housing crisis … Everyone’s on a waitlist,” Quintero-Cubillan said.

Both the UCSB administration and students are planning for an in-person school year while continuing to navigate academic dishonesty, travel restrictions, mental health difficulties and housing shortages.

At the Santa Barbara Independent, our staff continues to cover every aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic. Support the important work we do by making a

You must be logged in to post a comment.