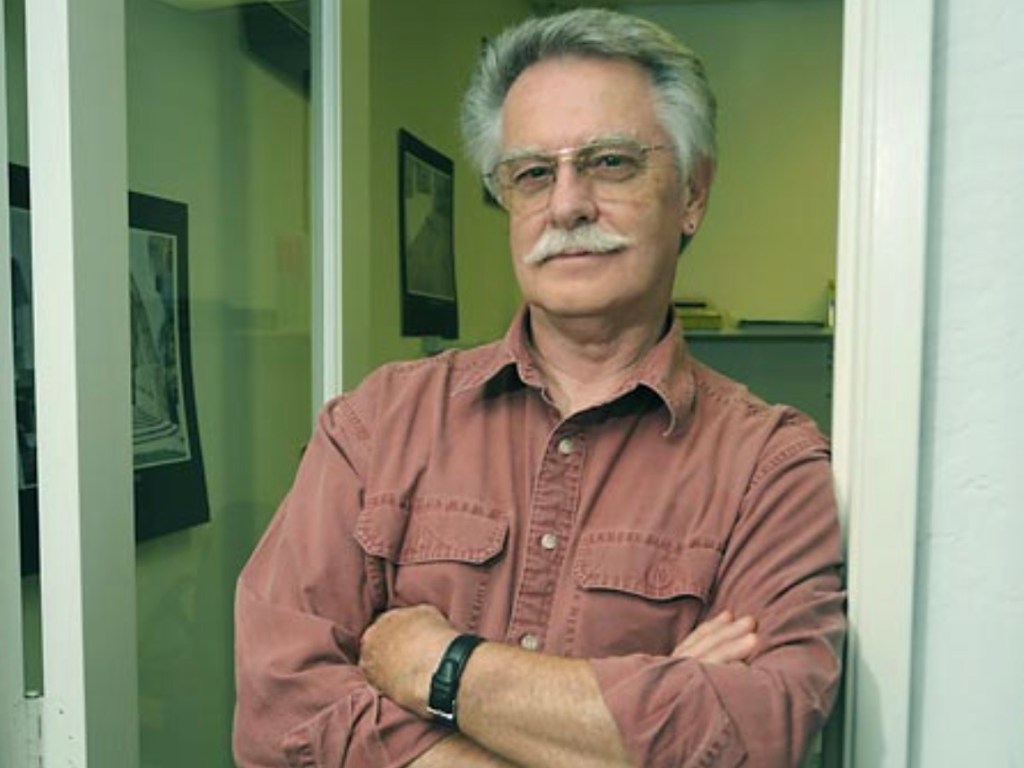

John Buttny, political consigliere, policy advisor, and fourth-floor strategist for two 3rd District supervisors — Bill Wallace and Gail Marshall — died this past week after a long struggle with Parkinson’s disease.

A pivotal player in South Coast environmental circles for nearly 30 years, Buttny combined street smarts with tactical pragmatism, combining the two with swagger, a twinkle of the eye, and a willingness to go for the jugular — on occasion. For most of his public life, Buttny managed to be both high-profile and behind-the-scenes, fighting growth and development in the Goleta Valley, slumlords in Isla Vista, and oil companies wherever he could find them. He was part of an aggressive slow-growth, no-growth machine that would emerge out of Isla Vista in the late 1970s, specializing in high-impact, door-to-door get-out-the-vote campaigns that relied on Isla Vista’s bounty of younger, left-leaning voters.

He played a role in the successful effort to take over the Goleta Water District Board of Directors with slow-growth candidates in the late 1970s to limit development. Once in office, they declared a water moratorium on new development.

Buttny, born in 1938, cut his teeth politically fighting the War in Vietnam in the 1960s. As such, he was active in the Students for a Democratic Society at the University of Colorado — where he attended graduate school. Later — and only briefly — would he be involved with the Weathermen, the radical left organization started in the late ’60s that would come to be known as the Weather Underground. He left, he stated, before the organization embraced more violent methods.

Get the top stories in your inbox by signing up for our daily newsletter, Indy Today.

Famously, Buttny would be arrested and charged with five felonies for his role in antiwar protests — and the violent police response — that broke out amid the mayhem of the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. This criminal “past” would be resurrected by Buttny’s political opponents over the years, for which he never made any apologies. The circumstances, he insisted, justified civil disobedience.

Bringing Buttny to Santa Barbara was Bette Robinson, whom he would marry. Although Buttny emerged out of the rough-and-tumble of Isla Vista politics, he and Isla Vista cityhood advocates famously never saw eye to eye. Buttny would serve as administrative assistant to 3rd District Supervisor Bill Wallace — for years the most outspoken environmental vote on the Board of Supervisors — and later Gail Marshall.

When Marshall was elected in 1996, the district boundaries had shifted further to the north to include more of the Santa Ynez Valley. Marshall herself ran a nursery in the valley, and Buttny and his family would move there as well. At the time, North-South (ag-urban) rivalries were far more polarized than they are today — with North County interests forever threatening to secede from the county. (They eventually tried in 2006 and failed.)

In person, Buttny was shrewd, funny, and outspoken. Though passionate about his progressive politics, he parted company with what he described as the self-destructive purism of South Coast environmentalists when it came to legislative tactics and strategies when it came to saving oak trees from the wine industry as it took off in the early 2000s.

Walking into a political ambush in 2001 shortly after 9/11, Buttny and Marshall triggered a firestorm of controversy when they objected to the recitation of the pledge of allegiance at a Santa Ynez Valley planning meeting at which the pledge was typically not said. Before the meeting, Buttny and Marshall objected that patriotic displays were best conducted in private. But meeting organizers insisted and alerted the media there could be fireworks. Buttny and Marshall would recite the pledge, but not before expressing their reservations. Buttny would later object pledge proponents had wrapped themselves “in a bloodstained flag.”

All this precipitated a recall campaign led by former sheriff Jim Thomas. Playing a key role in the effort to keep Marshall in power was a young political activist named Das Williams, now the county’s 1st District supervisor. Marshall would weather the storm but would be badly bruised in the process.

In 2004, Buttny ran for county supervisor against Brooks Firestone, scion of the Firestone tire fortune and a moderate winegrowing Republican member of the State Assembly. That contest, like the recall campaign, would be intensely personal and hard-fought. When Firestone assumed office, Buttny briefly took over the helm of the Citizens Planning Association and then jumped into efforts to come to grips with the issue of homelessness. By 2009, he assumed the unofficial mantle of county homeless czar, taking the helm of Bringing Our Community Home, an organization that had drafted a 10-year plan the year before to end chronic homelessness.

This article was underwritten in part by the Mickey Flacks Journalism Fund for Social Justice, a proud, innovative supporter of local news. To make a contribution go to sbcan.org/journalism_fund.