When it comes to social media’s ability to facilitate dialogue, online interactions are often worse than the ones we see in the real world — especially when the topic at hand is anything of moral or political value. In large part, this is because social media operates as an outrage machine, meaning that it doesn’t just harbor frustration and moral outrage but promotes and encourages it as well.

If you were to ask anyone whether or not social media has been beneficial to political discourse, you will surely get a wide variety of answers. And although many will be quick to criticize, social media’s impact on human communication has no doubt been revolutionary, and sometimes even positive. Indeed, social media’s utility for diffusing information has been proven in numerous cases like when bringing people together to initiate large social change or serving as a space for activists to organize huge political rallies.

An additional truth about social media, however, is that it constantly seeks to shape our behavior towards conflict by prioritizing the most morally and emotionally provocative information.

That was the conclusion of a 2017 study where researchers at New York University used machine learning to analyze over half a million tweets. They found that tweets using more “moral-emotional” language (words such as evil, steal, etc.) were more likely to go viral. According to their analyses, the presence of each moral-emotional word in a tweet increased the diffusion of that message by a factor of 20 percent.

The idea that emotion shapes the virality of social media messages is now widely understood by media scholars and this effect generalizes to other types of online content as well. Looking at a dataset of New York Times articles, a 2012 study by Jonah Berger and Katherine Milkman found that articles that evoked more emotional arousal ended up being more viral.

This is worrisome. Not only because online platforms amplify the voices that generate the most emotional feedback rather than the ones offering the most nuanced, measured takes. But it’s also because when combined with another ugly trait of American political discourse, group polarization, it slowly distorts the perception of public dialogue and, in turn, the real world.

As echo chambers continue to form in online social networks, polarization continues to increase. Slowly but surely, partisans are forming two increasingly different digital environments where content that pushes the emotional buttons of one political side gets magnified in that respective network. This was demonstrated in the same 2017 study at NYU where they found that “the expression of moral emotion aids diffusion within political in-group networks more than outgroup networks.” Thus, what trends in the liberal networks is what gets the liberals riled up and what trends in the conservative networks is what gets the conservatives riled up—with little overlapping content between the two.

Older, more conservative folks love to talk about the ideological insularity that younger people experience while attending liberal universities. Yet partisans on both sides of the political spectrum are existing in digital bubbles that act in a similar, if not more, parochial manner. Instead of “indoctrinating professors”, however, partisans have powerful social media algorithms that are designed to strengthen their most primitive tribal tendencies and polarize them even further.

The crucial thing to recognize though is that, unlike four-year universities, it seems that there is no point at which partisans will need to leave their ideological bubbles. Going back to the college analogy, students will inevitably face the challenges of what older folks tend to paint as a scary and unforgiving “real world”. Once they graduate, they end up getting jobs where they have to work with others who hold different opinions than themselves. Soon enough, they’ll realize that they must abandon some of their closeminded tendencies adopted from college. Because — as they come to learn — in order for their workspaces to function properly, they need to be able to work with different types of people.

My point here is that this comparison is much more similar than we realize. Although there is no due date for which we must exit our insular social networks, we are, as members of the same political process, working towards a shared goal: the future health of our democracy. This can only be achieved through a healthy marketplace of ideas and a citizenry that has an accurate perception of this marketplace. However, the truth is that we currently live in emotionally charged informational landscapes designed to distort the baseline for which we might consider a moderate political stance.

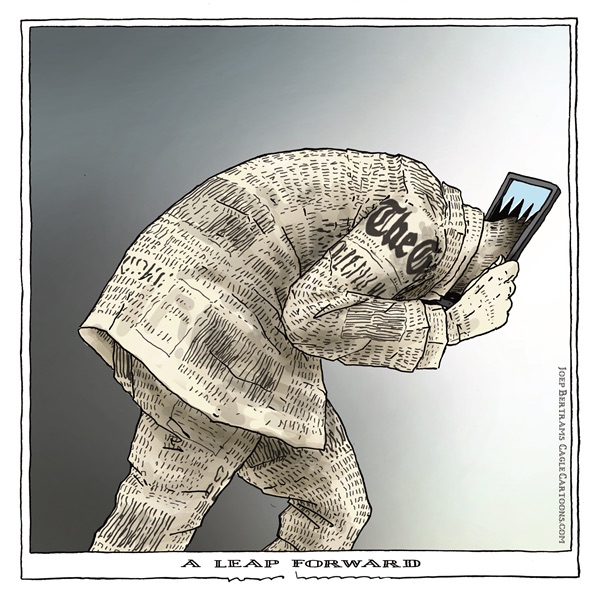

Additionally, the phrase “currently live” is used quite literally. As people become more and more plugged in, it becomes increasingly clear that our online behavior is our behavior. In that sense, “our online public discourse” is just “our public discourse.” We can no longer meaningfully dissociate online political engagement from real-life political engagement.

With all that being said, how do we begin to rectify our online behavioral patterns so that they represent a healthy political system or, perhaps, a political system that we are more used to? Well, one quick solution might be to treat our online behavior like real-life behavior. Because although online interactions may feel detached and inauthentic, they have tangible effects on our democracy. Our online behaviors do, in fact, influence how we vote and how we view the world.

Therefore, in an attention-hungry, outrage-oriented digital world, we need to constantly strive for meaningful engagement. Of course, this will be tough. We are working against powerful social media algorithms that want nothing more than to present to us the most polarizing stimuli. But with stakes so obviously high, it’s becoming more and more clear that mitigating these problems are crucial for the maintenance of a healthy political enterprise.

At the end of the day, it is up to us to be mindful of our online behavior and measure the accuracy of our perceptions because, if left unchecked, our online environments will continue to distort our most fundamental understandings. However, none of this can be achieved until we shed the false notion that our digital worlds exist in a vacuum with no real influence on how we think and behave politically.