In Goleta City Council Race, Five Candidates Face Off for Two Open Seats

Councilmembers Kasdin and Richards Challenged by Wallace, Shores, and Wallach

This article is part of an ongoing series of candidate profiles ahead of the General Election on November 3, 2020. Stay tuned to our Election 2020 page for all of our latest profiles and election coverage.

Three candidates have stepped up to challenge the two incumbents running for re-election to the Goleta City Council, but all three believe the city is well-run and focused on subjects they care about — careful growth, keeping open space, and improving the environment. It’s more a question of style rather than issues that distinguish the candidates, though all are concerned about the effect of coronavirus on Goleta’s economy.

A revenue loss to Goleta of $5.8 million is expected this fiscal year, and a ballot measure to add a one-cent sales tax increase — being studied before the pandemic hit — was narrowly defeated at council, which was split between the need to provide services and the impact on the poor and the unemployed. To counter the projected revenue loss, the city put itself on hold, postponing major projects and freezing new hiring.

That five are running for two seats is a hallmark this year compared to the races in 2014 and 2018, when the city barely had the candidates to take the empty seats. The more competitive field this year could be a sign that the city’s Public Engagement Commission has been successful. Created to raise civic participation ahead of district elections in 2022, the commission recommended raising councilmember compensation from $7,000 a year to $42,000, which voters approved in 2018, and switching from afternoon to evening meetings.

Among the five are a teacher, an analyst, a businesswoman, a car-dealership service manager, and a writer, each of whom participated in a conversation that is summarized below.

Get the top stories in your inbox by signing up for our daily newsletter, Indy Today.

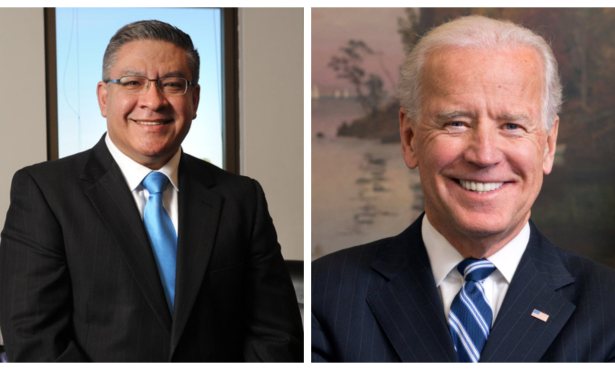

Stuart Kasdin: Priorities in Order

On the City Council dais, Stuart Kasdin, who received the greatest number of votes in Goleta’s 2016 election, has been able to test the governmental theory he’s studied and now teaches — currently at Santa Barbara City College, formerly at George Washington University in the nation’s capital. One process he thought could be improved was in priority planning; the trouble was that councilmembers could ask city staff to prioritize a favored project, which distracted from ongoing work. A study of the planning department in 2018 came to a similar conclusion, by which time Planning Director Peter Imhof had taken the reins, coming from the county which has a similar priority system.

“The priority list, with a timetable for when things get done, gave us a sense of where things are, how we’re moving ahead…. Staff had the reassurance that we weren’t going to bean them with additional expectations and hold them accountable for things they couldn’t achieve,” Kasdin said.

The result, Kasdin noted, was the completion of several long-languishing projects, such as the overhaul of the zoning ordinance, a relic from 2001, when the county controlled Goleta; the butterfly-grove management program; and Jonny D. Wallis Park, which had been a sign on a fence since 2011. Old Town’s sidewalks are now nearly finished — another long-talked-about project — and a creeks and watershed study began in September.

For better or worse, Kasdin noted, the city has a plethora of strategic plans, which he believed were good in some areas, such as homelessness. But even there, he suggested that staff and everyone step back a bit and look at who was being funded.

“We were giving the Salvation Army money to hold a bed for the city, but they were restrictive about who could stay there,” he said. Santa Barbara PATH was a better fit, they learned, after instead funding a nonprofit that would assess the services that would work best for Goleta’s homeless people. “We were able to send the right people to the right shelter and have that bed be used,” Kasdin said.

The issue that swept Kasdin, Councilmember Kyle Richards, and Mayor Paula Perotte into office in 2016 was former councils’ approval of massive developments that held hundreds of dwellings each. “Is that still an issue?” Kasdin asked incredulously when his interviewer observed that the city’s available space was already claimed. “Because of RHNA” — the Regional Housing Needs Allocation, a state mandate to the county to add homes — “Goleta potentially faces 1,500 or more new units over an eight-year period,” he said, underlining that the number is just an early projection. With the city’s big undeveloped parcels gone, the housing would likely be built through rezoning or projects approved in already developed areas.

In California, “the biggest cost is housing. People can’t live where they work; it’s expensive; it can cause homelessness problems,” Kasdin said. “It’s an issue for all cities, but I don’t know how it will play out,” he said, adding that the State Legislature introduced new rules every session. For instance, a new proposal by Sen. Scott Wiener of San Francisco would eliminate single-family zoning and require multi-unit dwellings in their place, Kasdin noted. SB902 passed the Senate and is now in the Assembly’s Local Government Committee.

Asking voters to raise Goleta’s sales tax by a cent did not make it onto the November ballot in part because of Kasdin’s opposition. “Having worked in budget a long time and with a background in it” — for 12 years, Kasdin was part of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget — “the whole point of priorities is to set priorities,” he said.

“You can’t achieve anything you want without limitation,” Kasdin continued. “There’s always some sort of financial triage you have to do. If there was a pressing need for additional revenue, we need to identify that. But getting money for the sake of getting money — I couldn’t justify that, especially when we were talking about a sales tax that would affect everyone, including the poor in our community.”

The exercise was not unlike an experience he had in Ecuador, where he was sent by the Peace Corps years ago. Kasdin was to evaluate a farm whose owner asked for a grant to buy cattle. The pasture was of poor quality, and he wondered if it was better cattle or improved pasture that would actually help the rancher. He ended up suggesting that they fund pasture improvements, give it some time, and then evaluate the need for cattle.

“Likewise, for taxes,” Kasdin said, “you have to understand what is really needed and then make an evaluation of what the best solution is.”

Kyle Richards: A Whirlwind of Information

“Coming into this four years ago, I felt like the city was a ship that was going in the wrong direction,” said Kyle Richards, who came onto the council in 2016, running on a platform to control the immense developments that were then rising along Hollister Avenue, obscuring the mountains and making the majority of voters feel like they were losing their small city. “It needed to be steered in a different way, and over time, we’ve changed direction. And I think we now need to stay the course.”

The analogy is an apt one, too, as “Goleta” in Spanish translates to “schooner,” and Richards is equally accurate in the details when he speaks of all things Goleta. He’d rather see “smart growth,” Richards said, and is proud of the council’s ability to support a change in the vast Westar/Hollister Village development. The last remaining piece of that development was “the Triangle Property,” originally slated to be mostly commercial shops and workshops with a bit of housing. A lawsuit by a neighbor, city negotiations, and the decline in storefronts due to the hegemony of online retailers combined to have Westar ask for an amendment to instead build studios and one-bedroom apartments.

“Housing has a lot less impact on traffic in the area than commercial uses, which have traffic all day long,” Richards said. “Or at least it did before coronavirus. Now everyone stays home all day,” he said wryly.

The virus and its effect on business have been obvious, Richards said. The city has used small grant programs to counter some of the pain, joining forces with Women’s Economic Ventures and the Santa Barbara Foundation to pool its money. In addition, an information campaign highlighting shops and retail areas was reaching people, he said. But the council’s failure to add the sales tax ballot measure was a blow.

Richards had advocated passionately for the need to keep funding city services: “That’s something I regret the most,” he said. “We’ve only begun to feel the economic effects of the pandemic, and I am concerned that we won’t be able to provide for residents” in terms of well-maintained roads, sidewalks, libraries, and parks, the bread-and-butter services that city government delivers to residents and businesses.

Richards has lived in Goleta for 23 years, arriving in 1997 with a master’s degree in education from Penn State to UC Santa Barbara, where he’s the policy analyst for the university’s Academic Senate. His undergraduate work at Penn was in environmental science, and Richards spends every weekend on a trail, if he can.

As mayor pro tempore for the past two years, Richards runs a meeting “that facilitates dialogue,” he said, “where people feel that they are heard and have a voice.” It’s something he’s come to learn, he said, having served on several boards, including the Fund for Santa Barbara and his own homeowner’s association.

“One of the things I really love about the Goleta community is the level of involvement, well, at least pre-COVID,” he said, citing the packed council chambers when decisions were made about the butterfly grove’s management plan. “We had to send it back,” he said of what they learned from the public comments. “There were so many in the community who were knowledgeable and told us more about the science and biology. We had to listen and incorporate their feedback.”

Richards said meetings with the Chamber of Commerce have helped him broaden his knowledge of other aspects of Goleta’s community, too. “I’m not in business,” he said, “and I’m eager to hear what it’s like for small businesses in the city. It was an opportunity to understand how city policies affect them.”

Richards has a long list of accomplishments he’s proud of, including the long-term projects that have finally crossed the finish line. New projects will benefit Old Town, which is where Richards lives. The San Jose bicycle lane will enable residents from Cathedral Oaks to bike and jog to Old Town and to Goleta Beach. And a related project will connect Ekwill and Foster streets from South Kellogg to Fairview Avenue, which will give motorists two more ways to access Old Town’s industrial area; the project also adds roundabouts on Hollister to either side of the 217 overpass, which will serve to both slow traffic and shorten wait times at the intersections, the engineers said when the project was approved.

Richards believes the traffic solutions will improve the quality of life for his neighbors and allow the city to continue to focus on parks and sidewalks in the area. Old Town’s coffee shops, grocery store, and feed store were regular stops for him, Richards said, though not always on a bicycle, his customary mode of transportation. The sharrows, in which cars and bicycles share a lane, are scary, he said, and bike lanes are something he hopes to see on that stretch of Hollister one day.

Blanche “Grace” Wallace: Just Call Me Grace

Aside from the two incumbents, the candidate who has probably put in the most time at City Council is Blanche “Grace” Wallace. (“Don’t call me Blanche!” she said of the need to put her legal name on the ballot: “Everyone knows me as Grace!”) She attends several times a month to speak on issues she’s interested in. Among those issues was the business improvement tax proposed for Old Town in 2019, which she feared would end up with tenants being kicked out and chain stores moving in to take their place.

“I’ve been very involved in learning the process,” she said, and she wants “government and community to work together for the common good of Goleta citizens.”

As part of the Old Town association, Wallace championed the planting of flowers along Hollister as part of a “Love Your City” campaign, she said, toting gallon jugs of water in a baby carriage to keep them alive and working with the city’s street maintenance crew to keep them in place. She gained donations from businesses so that she could stretch the funding from the city, and she’s proud that the project stayed within its budget, an accomplishment she thought she could translate to the rest of the city.

While the council has been doing a pretty decent job, Wallace said, one thing that concerns her is the new set of roundabouts that could break ground next year on Hollister at the State Highway 217 overpass. “I see mothers with two or three little ones cross the street there,” she explained, on their way to St. Raphael Elementary School, “and there could be a danger for them.”

Balancing open space and moderate growth would be another of Wallace’s goals on the council, she said. “I would like to maintain our open space,” she said, while at the same time noting how proud Goletans are that “we can stay right here in Goleta and go to our own nice restaurants.” She hopes to be a voice for small businesses to keep it that way.

Justin Shores: A Calling to Run for Office

Justin Shores has a burning ambition to better his adopted hometown of Goleta — he says it’s a calling. Currently a service manager at the Toyota dealership in Old Town, Shores said he wanted to work with residents, parents, and teens on gang issues; get homeless people off the streets; and be an advocate for business.

“I didn’t realize that gangs in Goleta were the number-one law enforcement issue until I spoke with Sheriff Bill Brown,” Shores said. “We need a voice on the council … to talk to the parents and get them more support in getting their kids off the streets.”

Were he elected, Shores emphasized, “My biggest goal would be to renegotiate the RNA with the county.” The RNA, or the Revenue Neutrality Agreement, is the incessant thorn in Goleta’s side; it’s also a plank in Councilmember Roger Aceves’s platform in his run for mayor. Shores met Aceves in 2005 when he sold him a car and has been “picking his brain” for information ever since.

The RNA, approved by voters when Goleta was created, gives the county a third of Goleta’s sales tax and half its property tax to pay for county services “in perpetuity.” As housing and retail in Goleta have grown — most recently a Target replacing a Kmart store — the agreement, arguably the world’s worst, seems more and more inequitable. Shores believes the city has a case to pursue and would commit the legal talent to pursue it.

He would have much to learn as a Goleta councilmember, Shores admitted, and said he intended to study and be well informed: “My calling is actually faith and politics. I want to be that guy that has that experience to mentor other people who want to get in.”

Of the work the city recently fostered to prune highway trees and bushes after two fires broke out near homeless camps, Shores, who grew up in Placerville in the Sierra Nevada foothills, said he understood the issue. “My dad was homeless. I used to visit him under a bridge,” he said. “He’d been an alcoholic, and I saw what happened.” The focus should be long-term, he advocated, not only counseling to end drug abuse and improve mental health but also jobs to instill a sense of purpose and personal responsibility. “I’ve been poor,” he said. “I understand how it is to struggle. But we can’t allow our town to be trashed and burned down.”

As an advocate for business, Shores thought the city should fight back harder to leave the state’s lockdown. “Hey, Mr. Newsom, or whoever’s in charge,” he said, “Goleta is a little different than Santa Maria. But we have to pay for the county’s COVID numbers.” Shores believed that doctors, not officials, should deal with the health side of the coronavirus. In his job, he wears a face covering 10-12 hours a day. “Everyone’s wearing masks,” Shores noted. “If they work, then businesses should be allowed to open up. Do masks work or not?”

Bruce Wallach: New City Ideas

To introduce himself as a City Council candidate, Bruce Wallach said he’s been knocking on doors around town; in return, he’s been learning about how Goletans feel about all sorts of things, among them the roundabouts at the 217 and Hollister, parking in the middle of Hollister, and a homeless shelter in the city. Wallach is entering his first run for City Council, having attempted the school board in 2018 and the water board in 2010.

Reviving Old Town, where Wallach lives, is something he’s pondered. He thinks a narrowed Hollister Avenue with parking in the center of the street could increase business dramatically, as a similar plan in Orange County had, and that the Hollister/217 roundabouts could end the traffic-signal wait times. “Some want them; some don’t,” he reported. One person was concerned the middle-of-the-road parking could endanger elderly people trying to cross to the sidewalk. “Is it good for Old Town to increase its business?” he asked rhetorically.

Wallach is a writer who has authored “simple fairy tales with animals that talk,” he said; he states he came up with the idea for Disney’s The Lion King. Making Goleta a beautiful, fun, and livable city is his goal, and some development, but not too much, was needed so that police and fire employees could live in town, he said. Among his outside-the-box ideas was to place housing in pockets amid the avocado groves. “Not a lot of people would be living nearby, and there’d be less traffic congestion,” he noted.

Correction: The sales tax proposed for Goleta was to add one cent, not a half-cent, per dollar.

Every day, the staff of the Santa Barbara Independent works hard to sort out truth from rumor and keep you informed of what’s happening across the entire Santa Barbara community. Now there’s a way to directly enable these efforts. Support the Independent by making a direct contribution or with a subscription to Indy+.

You must be logged in to post a comment.