On August 12, Phillips 66 announced it would be shuttering its Santa Maria oil processing facilities and converting its Bay Area refinery to a renewable fuels facility. This sudden turn of events dealt a serious blow to plans for trucking crude oil on Highway 101 and Route 166 — plans that are instrumental to ExxonMobil restarting three decommissioned offshore oil platforms and its Las Flores Canyon processing facility. But the announcement is also an unexpected opportunity to finally kick the oil habit in Santa Barbara County.

Exxon’s trucking proposal was part of a broader initiative to increase oil drilling across the Central Coast. It was meant as an interim solution until a pipeline is built to transfer oil from Gaviota to processing facilities in Santa Maria and Maricopa.

With processing now in jeopardy, hearings by the Planning Commission on the trucking proposal have been postponed indefinitely until Exxon reevaluates the project’s viability. In the meantime, county leaders should refocus efforts on transitioning Santa Barbara away from oil and towards a more just, safe, and financially prudent shift to clean energy.

Supporters say the development of petroleum infrastructure will increase local energy supplies and reduce the state’s reliance on foreign oil. They argue that oil is integral to Santa Barbara’s future and poses little harm with the right regulations and monitoring in place.

History begs to differ. While it’s been 51 years since the spill that forever altered the county’s coastline and the nation’s environmental policy, it’s only been five years since a pipeline ruptured at Refugio State Beach — the latest “six-figure” incident to spill over 100,000 gallons of oil. These accidents cost the county millions of dollars in cleanup, billions in lost tourism, and priceless damage to Chumash watersheds and cultural heritage.

In light of Phillips 66’s announcement, Exxon revised its proposal so that the Santa Maria Pump Station is the final terminal and no oil would be trucked to Maricopa, nor would tankers drive during heavy rains. Still, the updated staff report estimates up to 25,550 additional tankers on the roads each year. The county’s final environmental impact report identifies a significant unavoidable adverse risk (a “Class I” impact) in spilling up to 6,720 barrels of hazardous materials for each potential truck accident.

These accidents aren’t as rare as you might think. Just this March we witnessed yet another oil spill, this time by a tanker truck dousing 4,500 gallons of crude oil into the Cuyama River, threatening the reservoir that provides nearly 200,000 county residents with clean water. The truck was traveling on the original route under consideration, and veered off the highway because of “excessive speed for road conditions.”

It’s no wonder that a majority of residents oppose restarting ExxonMobil’s three offshore platforms, and oppose offshore drilling in general. Nearly 3 out of 4 residents are concerned about the specific dangers posed by oil tanker trucks on our highways. Not to mention vocal opposition, as the Sierra Club’s Katie Davis notes, “from Chumash elders to students to businesses to city councils.” Indeed, the trucking proposal is opposed by several local organizations, such as 350 Santa Barbara, the Central Coast Climate Justice Network, Sierra Club Los Padres Chapter, the Environmental Defense Center, and even the Santa Barbara City Council.

But these dangers are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the social costs of oil. Air pollution from onshore processing facilities — the Santa Maria Pump Station is just a mile down the road from Battles Elementary School — pose a persistent health risk for neighboring residents, one that is predominantly felt by communities of color and by low-income households.

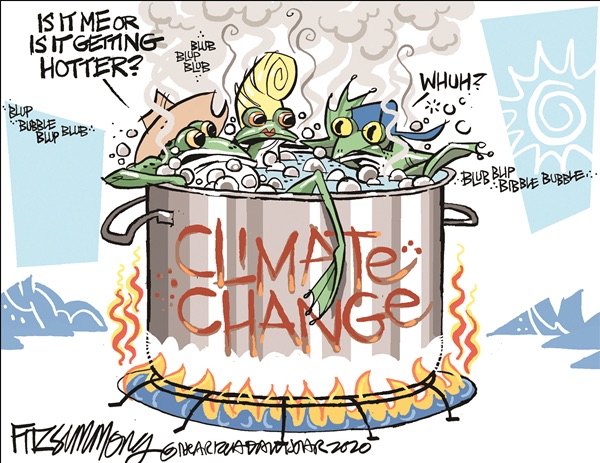

The routine burning off or “flaring” of gas — a byproduct of oil extraction — contributes to the county’s greenhouse gas emissions, and often goes undetected. And the ongoing production of petroleum continues to fuel climatic changes that are directly linked to local disasters like the Thomas Fire, the Montecito mudslide, record-breaking temperatures, and years of persistent drought.

Even the petroleum industry itself has started questioning the future of oil. In early August, BP announced it would be slashing oil production by 40 percent, ending any new oil exploration activity, and increasing its renewable and low-carbon investments ten-fold by 2030. And in July, the French multinational company Total publicly acknowledged that any of its oil fields producing beyond 20 years would be “stranded” and left unproduced, effectively wiping off over $8 billion from its assets.

Why, then, would our county support the resumption of oil production — especially when Big Oil is abandoning new projects and seriously considering a future without oil?

Enough is enough. The future of oil has no future that Santa Barbara should be a part of. The Planning Commission needs to deny the trucking proposal — if and when it is rescheduled — and any future projects that propose continued extraction of petroleum within the county.

Instead of doubling down on the fuel of the past, and one that has produced so much harm, let’s spend the county’s time and efforts on renewable and low-carbon developments that could spur thousands of jobs and a clean future.

Paasha Mahdavi is an assistant professor of Political Science at UC Santa Barbara.