When the Badge Gets Tarnished

Santa Barbara Sheriff on George Floyd’s Inhumane Death

As new sheriff’s deputies or custody deputies begin their careers with the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Office, they must solemnly swear to support and defend the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of California. During the swear-in ceremony we incorporate a badge pinning that is usually done by a loved one. I always give a speech about the badge that each of us wears or carries as a law enforcement officer. Many of my executive, command and support staff have heard that speech dozens, if not hundreds, of times, but I believe it is a message that bears repeating.

I advise the newly minted deputies that the badge is the most important accoutrement they’ll have as a peace officer. The symbolism of the badge, whether it’s a star-shape or an oval, is always the same. It represents an ancient warrior’s shield — a shield of protection. The symbolism is two-fold, representing the protection we provide to the community, and the protection that the community provides to us, such as in enhanced penalties for those who would do us harm. The seven-pointed star shape of our badge is an ancient symbol that some say represents good over evil. Each of the seven points on the star corresponds to the letters in the word S-H-E-R-I-F-F and stands for a value we should strive for in our daily work: Service, Honor, Ethics, Respect, Integrity, Fairness, and Fidelity or Faithfulness. The finish of the badge is gold, representing something precious.

Most importantly, I tell these new cops that the badges they are receiving are new, shiny, and untarnished. I always admonish them that the badge must be carried and worn with honor. It is a symbol of the public’s faith in us, faith that we will carry out our great responsibilities honorably. I also tell them that the badge will not be theirs forever. There will come a time when they are going to have to pass that badge over to someone else who will take their place. When they do, it is imperative that the badge remains shiny, for if they do anything to tarnish it — either while on or off-duty — they don’t just tarnish their own badge, but also the badges of all of us in the Sheriff’s Office, and of every member of the law enforcement profession.

Sadly, what we saw happen in Minneapolis on Memorial Day tarnished all of our badges.

I don’t usually weigh-in with an opinion in the immediate aftermath of a use of force by members of the Sheriff’s Office or another law enforcement agency because, inevitably, all the facts and circumstances of the event are not known at first. Any use of force, no matter how justified it may be, is ugly to watch. Threats, perspective, and vantage points may not be apparent on first glance, and information is often discovered or developed during a subsequent investigation that can be mitigating or justifies the type and amount of force that was used.

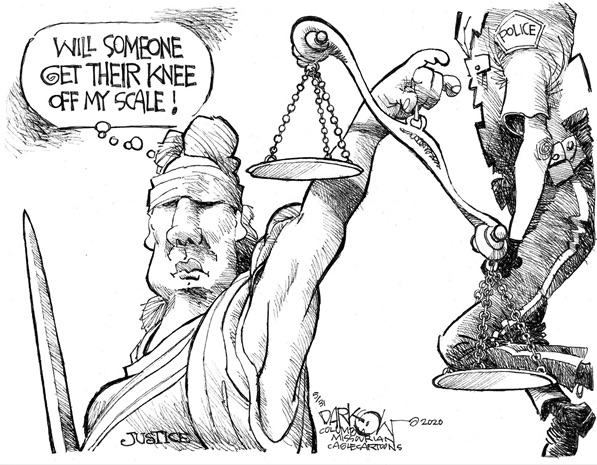

In the case that is the focus of our current national conversation, however, there is no justification for an officer kneeling on a non-resistive person’s neck for more than 8 ½ minutes. Witnessing Mr. George Floyd’s inhumane, painful, and unnecessary death was horrifying and gut-wrenching for me. I also immediately realized that even though this reprehensible act occurred 2,000 miles away from us, it would inflict damage on the relationships between many California law enforcement agencies and communities of color.

I recognize the anger that our African-American brothers and sisters across the nation feel as a result of this terrible and unjustified killing of a man arrested for a low-level crime. It’s okay to be angry. I myself am disgusted, deeply saddened, and angry about what I saw. Frankly, I’d be concerned about anyone who isn’t angry about what happened.

The large numbers of peaceful protests across our nation are welcomed. Freedom of speech, the right to petition government for redress of grievances, and freedom of assembly are all guaranteed under the federal and state constitutions that we in law enforcement are sworn to support and defend. I don’t agree with some of the inflammatory rhetoric I’ve heard at some of those protests. I don’t condone some of the visuals I’ve seen, like signs bearing profane slogans against the police, or a severed and bloody pig’s head being carried by a protester. I think those types of actions hurt the protestors’ cause, and I wish I heard more community leaders and organizers speak out to condemn them. But no matter how much I may disagree with certain aspects of the protests, I will always support and defend the rights of people to express themselves in those and other ways.

What is not okay is the widespread lawlessness that is being blamed on the aforementioned anger. Acts of arson, vandalism, looting, and beatings of store owners. Shootings, fire bombing and aggravated assaults against peace officers. Those activities can never be justified or excused; they endanger our communities, they undermine our fragile economy already heavily damaged by the COVID-19 pandemic, and they shatter the hopes and lives of small business owners. The people who commit these crimes attack our American way of life and they profoundly dishonor the memory of George Floyd.

As a nation and as a people we must not conflate these two groups of individuals. We must recognize the distinct difference between peaceful protestors and those so-called “protesters” who loot, deface, and burn neighborhoods across America. It is equally important that we recognize the difference between the vast majority of good cops — who are brave and decent people willing to put themselves in harm’s way to protect others no matter their race, creed, or color — and the very, very small percentage of bad police officers who abuse their authority and engage in brutal or otherwise unlawful behavior.

It is also important for everyone to understand how infrequent fatal confrontations between the police and members of the public actually are. Consider this. While deaths at the hands of the police are uncommon, deaths of unarmed people are rare. According to the FBI and the Washington Post, 1,004 people were killed by law enforcement officers in the United States last year. The overwhelming majority of those deaths were justifiable homicides committed by officers defending their lives or the lives of other people. Of those 1,004 killed, 41 (4 percent) were unarmed. Of those 41, 19 were white and 9 were black. (The remaining 13 were either Hispanic or “other,” including Asians and Native Americans.)

Please don’t get me wrong. Just because cases like the unjustified killing of George Floyd are rare doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be concerned about them, or shouldn’t work to prevent them. Quite the contrary, we must do everything we reasonably can do to stop anyone from dying so senselessly and unnecessarily in the future. Steps that can be taken toward that goal include enhanced law enforcement training in a variety of areas, especially in an officer’s duty to intervene if another officer is using excessive and/or unnecessary force. Police and members of all communities should seek to better understand and know each other. Certain communities need to achieve positive changes in both police and community culture, as well as improvements in police-community relations. Such changes need to be driven by both law enforcement officers and members of the community.

At this point in our nation’s history there should also be a universal call for justice. Justice for what happened to George Floyd, and for anyone else who has been the victim of unlawful police misconduct, but also justice for the federal officer who was slain in Oakland and his family, for the five cops in Las Vegas and St. Louis who were shot while trying to restore order, for the hundreds of cops across our nation who have been injured as a result of recent civil disturbances, and justice for the countless shopkeepers and small business owners whose life savings and dreams have now been burned, stolen, or destroyed. They, too, deserve justice.

At the beginning of those swear-in ceremonies I mentioned earlier, I advise our new deputies to always practice the Golden Rule of Good Law Enforcement. That is, after each and every encounter they have with another person, whether a colleague, a member of the public, a criminal suspect, or a jail inmate, they need to ask themselves this important question: If I was that person, would I honestly feel as though I had been treated fairly, courteously, and professionally? I tell them that if the answer to that question is yes, then they’re doing a good job. If the answer to that question is no, then they need to recognize what was missing and make it right the next time.

We value professionalism in the Sheriff’s Office, and we are committed to having the best in our agency. The best training, the best equipment, the best policies, and, most importantly, the best people. We’re certainly not perfect, because we’re human, but we strive for excellence as we work to achieve our five core values: Service, Integrity, Caring, Courage, and Fairness.

The way Mr. Floyd was treated is the antithesis of good police work. I would never stand for that as your sheriff, but more importantly, none of the members of the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Office would ever stand for it either. To move past this tragic moment in our history we must come together with our community partners, especially those in our minority communities. We must communicate with each other, learn from one another, and build or mend bridges of trust between each other.

Prior to being elected sheriff I had the privilege of being Lompoc’s police chief. During my first week on the job I had a visit from Reverend Dan Tullis, the African-American pastor of the Grace Temple Missionary Baptist Church. He was a huge man with a booming bass voice, and when he shook my hand I remember his hand was so large I thought he might be wearing a catcher’s mitt. Dan told me he wanted to welcome me to the community, to get to know me, and to be a resource for me. At the conclusion of our brief meeting he gave me his card and said, “Call me if you need me.”

That encounter began a friendship that lasted for the next 13 years. Dan and I soon began to meet for lunch regularly. I discovered that his heart was even bigger than he was. He told me of his upbringing as the son of a poor sharecropper, and how he picked cotton as a child in the humid Alabama heat. He shared personal stories of the racism and intolerance he experienced growing up in the deep south, and during the beginning of his 20-year Air Force career. He also taught me how through God’s grace he was able to put those inequities behind him, move forward, and become a successful minister who led the same church for 22 years. We found we both wanted our people — his congregation and my officers — to do what was right. He taught me the importance of trying to see things from the viewpoint of people who didn’t grow up like I did, and I think I taught him the exact same thing.

Dan and I became friends, and from our friendship we developed a deep and abiding trust for one another. We talked about things people are afraid to talk about: politics, religion, race relations, death, and how lonely it can be at the top. Although we often disagreed and argued, we never got mad at one other. We respected each other, and we were resources for each other. Dan had a wonderful sense of humor, and we constantly teased each other and laughed together. Whenever I was with him he lifted me up. When he died in 2009, his family asked me to eulogize him at his memorial service, something I will always consider to be one of the great honors of my career. Not all cops and persons of color are going to be able to develop the type of relationship that Dan and I had, but I sure hope they try.

Our badges were tarnished by what happened in Minneapolis, but we will continue to work in ways that will restore their luster. We’ll do so by continuing to practice good community policing, partnering with those we serve to identify and solve problems relating to crime, fear of crime, neighborhood decay, and quality of life issues. We’ll build on old relationships and develop new ones. We’ll continue to seek alternatives to incarceration for those who suffer from substance abuse and mental illness, and we’ll continue to give inmates in our jail the tools they need to be successful when they are released. We’ll listen more, talk less, and hold each other accountable. Above all, we’ll strive to treat people fairly, courteously, and professionally.

We’ll do all that because as peace officers we are a part of, not apart from, our community. It is an honor to serve and protect all the people of Santa Barbara County. We stand with you, and we are here for you during this painful and difficult time.

Bill Brown is the sheriff of Santa Barbara County.