Santa Barbara’s Home Winemakers

Carrying on Long, Celebrated Tradition of Making Wine for Passion’s Sake

Home winemaking in Santa Barbara stretches back to the colonial era, but the modern era kicked off in grand fashion in the 1950s, when bacchanalian grape stomps went down on Mountain Drive. Many uphold that tradition today, and here are three passion-driven projects that have stood true tests of time.

In a rare public showing, all three will be participating in the Santa Barbara Culinary Experience at the Hotel Californian on Sunday, March 15, speaking about their experiences and pouring selected wines at 11 a.m. Tickets are $30. See sbce.events/events/home-winemakers. [Due to public health concerns, the Santa Barbara Culinary Experience has been postponed to March 2021.]

Companeros

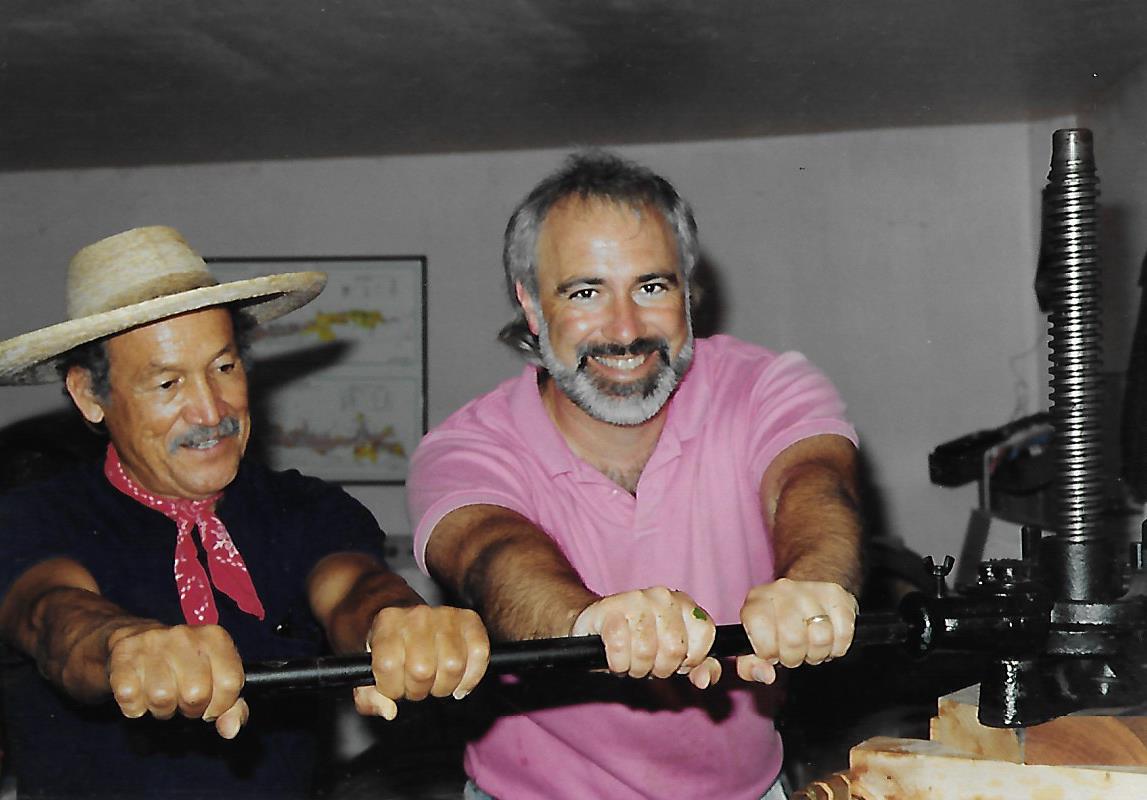

“It was our church,” explained Antonio Gardella of the early days of Companeros, the project he started in 1985 with Sid Ackert, Luis Goena, and, eventually, Art Morel. “Every other week, we’d get together on Sunday and spend four hours together. We just enjoyed the friendship, and getting your hands dirty with grapes is always so much fun.”

Gardella got his start by helping Jim Clendenen and Adam Tolmach at Au Bon Climat in the early 1980s. When Tolmach left Au Bon Climat to focus on the Ojai Vineyard, he invited Gardella and friends down for harvest in 1985. “Adam said, ‘Why don’t you pick some and make your own wine?’” explained Gardella. They rescued enough zinfandel to foot-stomp their first barrel of wine.

For a winery, Ackert, a retired aerospace engineer, offered an old horse stable surrounded by oak trees on his Rattlesnake Canyon property. They cleaned it up and acquired stainless-steel tanks that had been used as soup vats by the Lompoc penitentiary.

The name was suggested by Goena. “He was a real Zorba the Greek character,” said Gardella. “‘Companeros’ just means ‘buddies.’”

Companeros was producing up to 12 barrels a year at its peak and had 26 barrels in the winery at one point. They won hundreds of gold medals and blue ribbons at fairs around the state and garnered praise from renowned critic Robert Parker as well as Julia Child, Fess Parker, and numerous winemakers.

In 2009, the Jesusita Fire burned down Ackert’s house and their winery. The Companeros downsized, moving into a small room in Morel’s house, where they still make wine today. Goena passed away in 2014 — “There were 900 people at his funeral,” said Gardella. “We served 33 cases of Companeros wine” — and Ackert died four years later. His son, David, joined the buddies, as has winemaker Craig Jaffurs, who came onboard after selling his eponymous winery.

They’ve produced more than 300 different wines and counting. “It’s a labor of love more than anything,” said Gardella. “We’ve had wines that we poured down the creek, but overall, we’ve been very happy and lucky.”

Los Cinco Locos

“The last thing I wanted to do was go into the wine business,” said Dick Shaikewitz. But the first thing this attorney from St. Louis wanted to do upon retiring to Santa Barbara in 1997 was make wine for fun.

Then Shaikewitz met Montecito resident Lou Weider, who owned a large ranch in Paso Robles that grew wine grapes. To their winemaking team they added ophthalmologist Dr. George Primbs, who came up with the name Los Cinco Locos, or “The Five Crazies”; biophysicist John Van Atta, who also happened to own a critical pickup truck; and Howard Scar, whose horse stable the team turned into a winery.

In 2000, after buying used barrels from Chris Whitcraft as well as a destemmer and a press, the Locos made three barrels of wine from Weider’s vineyard. With help from winemakers such as Bruce McGuire, Steve Clifton, and Craig Jaffurs, they steadily expanded vineyard sources to such places as Bien Nacido, Kick-On Ranch, and Lucas & Lewellen.

Today, it’s mainly Scar and Shaikewitz making the wine. Van Atta and Weider passed away, and Primbs has dementia. Along the way, they learned what most professional winemakers would also attest to: “If you go find great grapes and don’t mess it up, you should be able to make a good product,” said Shaikewitz. “If you start with bad stuff, you need to be a magician!”

Pagan Brothers

“Our forefathers made wine to play in. We’re gonna make wine to drink.”

That was the sentiment behind the second founding of Pagan Brothers, which is the reincarnation of the Pagan Brothers’ Golden Goat Winery, founded on Mountain Drive in 1952 by “Wild” Bill Neely, a potter and park ranger, and adobe architect Frank Robinson.

When Wild Bill’s son, Chris Neely, and his friend Norm Grant decided to dust off the old digs and start anew, the idea was more precision than partying. “We decided that we drink so much wine, we might as well start making it,” recalled Grant of their 1981 decision. “And Chris said, ‘I have the perfect place.’” A Santa Barbara native, Grant knew of the Mountain Drive grape stomps and had been to Neely’s house before. But he was “totally surprised” to learn that the old winery was on his friend’s property, just down the hill.

They cracked open an old door to find an intact winery, albeit dusty and outdated. “They just abandoned it,” said Grant of the winery’s mid-’70s demise. Even the old equipment from Santa Cruz Island’s 19th-century winery was still there. “They bought equipment that was 50 years old in the ’50s — it was turn-of-the-century stuff,” said Grant. “We threw out all of the old vintages sitting in barrels, cleaned it up, and started making wine.”

The original process was pretty crude. They used the old hand-crank crusher that spilled the harvest onto chicken wire, where they scraped the fruit from the vines. “It was pretty rough on the hands,” said Grant. “Talk about black fingers.” After the juice fermented, they’d put the must into the basket press, which could process about a quarter ton at a time. From the must cake, Bill Neely made grappa for a few years before dying in 1985. Eventually, the Santa Cruz Island Foundation reclaimed the old equipment but bought the Pagan Brothers a brand-new press and crusher/destemmer.

Today, the group includes Grant, who invented a wine preservation device in the 1980s and sold that company about seven years ago; his daughter, Allie Grant, who’s worked in the commercial wine business for nearly a decade; the hot tub mogul Gary Gordon, who joined in 2001; Greg Geyer, a jeweler who lives in Grant’s neighborhood; and screenwriter/author Jerry Freedman.

In 2000, the winery was moved to Grant’s house on Cheltenham Road. “I built the house with that in mind and made sure we had a spot,” he explained. “It was a big transition to go from working down in this little canyon to coming up to a concrete slab and cool barrel room.”

Production is still quite small, usually just one to two barrels a vintage, sometimes three. “What we’ve learned over the years is that if you pay a little more for the grapes and keep everything clean, it all works out,” said Grant. “That’s about all we do.”

A longer version of these profiles will be published this fall in Vines & Vision: The Winemakers of Santa Barbara County, a book by Matt Kettmann and Macduff Everton. See vinesandvisionsb.com to order a copy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.