By late 1969, the fog of war seemed everywhere. The struggle in Vietnam was raging and young men were being drafted to fight an increasingly unpopular conflict. Protests were breaking out on college campuses and spilling into the streets of our cities. A younger generation was questioning “the establishment,” calling for changes – even a revolution – while seeking brotherly love and a more peaceful existence.

By early 1970, student activism hit the sleepy campus of UCSB and then engulfed its neighboring bedroom community of Isla Vista in three major disturbances in February, April and June. In the fog of these conflicts, one encountered smoke, tear gas, arrests, beatings, and brutality. Hundreds were arrested. One was killed.

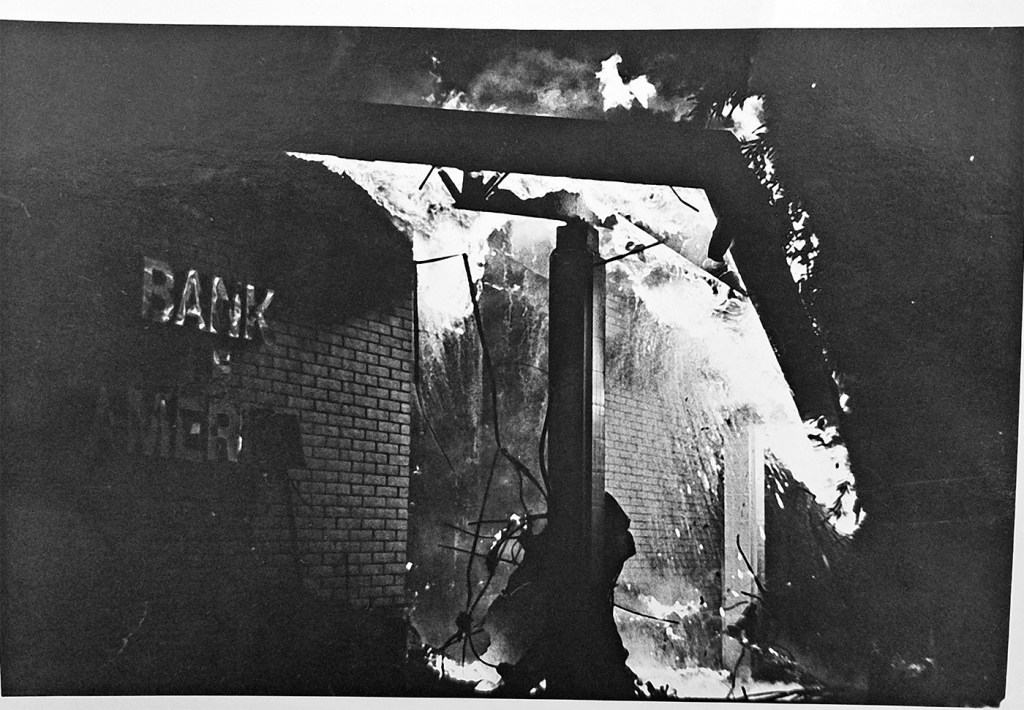

At the core of each of these disturbances was a so-called symbol of the establishment – the Bank of America, located in the heart of I.V. In one seminal moment that was to trigger the first of three riots and capture the headlines of the entire country, the Bank of America was burned to the ground. The date: February 25, 1970.

I stood across the street that night on Embarcadero del Norte in Isla Vista. Like dozens of others around me, I watched as a burning dumpster was being rammed through the bank’s doors; catching the curtains inside on fire; spreading to anything that would burn. It wasn’t long before the entire structure was ablaze and collapsing in on itself. By dawn, all that was left were smoldering embers, a couple of the walls and an erect, but freakishly twisted metal vault that miraculously hadn’t melted. The bank burning and the nights of street warfare that followed can only be described as surreal.

I was junior at UCSB majoring in Political Science when I watched the bank burn down. I was also active as a programmer with the campus radio station KCSB, becoming its General Manager in my senior year. I was one of several KCSB staff members who filed live reports during the I.V. unrest.

In 1972, a year after graduating from UCSB, I received a grant from the Regents of the University of California – “guilt money” it was nicknamed – to become a media liaison between Isla Vista and Santa Barbara. My role was to provide radio reports to the Santa Barbara’s radio stations that would talk about the beautification and construction efforts taking place in Isla Vista by its active and creative Community Council and Planning Commission. I thought my reports would help bridge the distrust between the two communities that had been intensified by the riots.

While filing these reports, I also anchored KCSB’s broadcast of the Captain Joel Honey hearings – the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s deputy who was accused of brutality during the Isla Vista disturbances. (Capt. Honey was found guilty and subsequently dismissed.) I discovered a bunch of tapes at KCSB with recorded audio of the riot coverage by the station’s reporters. I then set about to create a two part radio documentary using those recordings. The first documentary would re-capture the stories and sounds of the Isla Vista disturbances; the second focused on Isla Vista’s future.

With the help of KCSB’s news director, Lisa Osborn, we have re-mixed the first part of this documentary and are making it available for you to listen. I must admit it has been rather eye-opening to re-visit this documentary over the past couple of weeks – some 48 years later. Not only does it remind me of my shortcomings as a want-to-be reporter and producer back then, not to mention the unnerving upheaval that was taking place around me, but the documentary is also hauntingly fresh about who we are as a people and country today – divided, fragmented, untrusting, angry and fearful. Hear for yourself.

Editor’s note: Tim Owens did go on to enjoy a successful broadcasting career. He has been awarded two Peabody’s for his work with National Public Radio in Washington, DC, and other distinguished honors for his work in broadcast management. Tim returned to Santa Barbara in 1997. (Unfortunately, the tape of part two of the documentary – “The Future of Isla Vista” – cannot be found.)