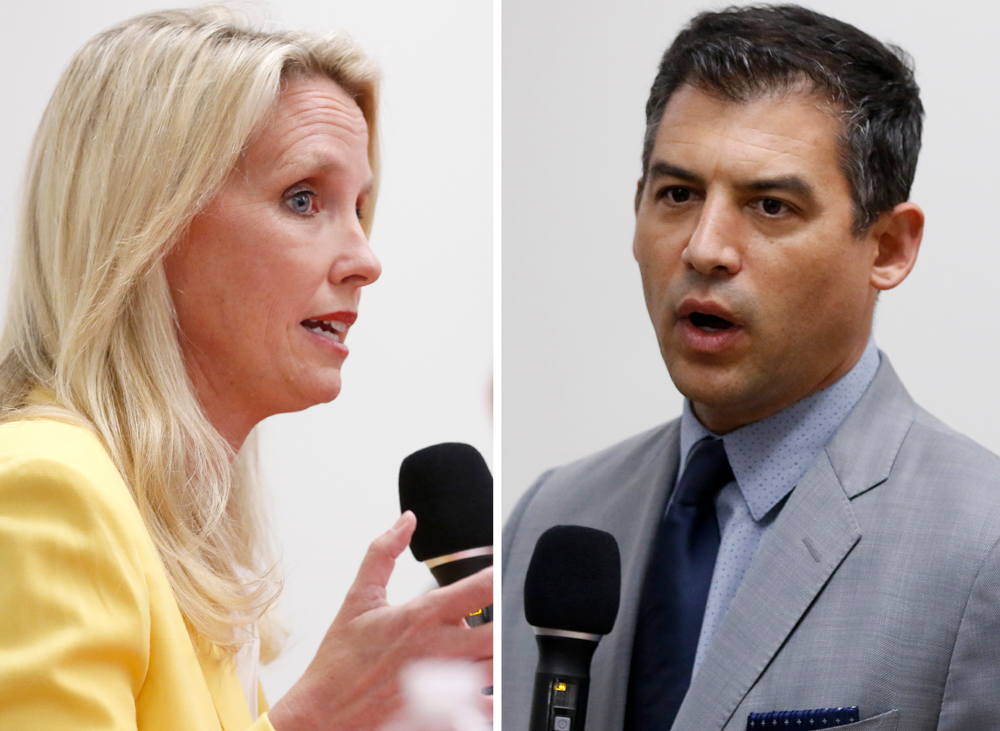

The contentious issue of cannabis and the influence of special interests on the political processes dominated the fourth public debate — hosted by the Santa Barbara Independent and held at the Franklin Community Center last Thursday night — between challenger Laura Capps, president of the Santa Barbara school board, and incumbent Das Williams, both vying for the 1st District county supervisor’s seat.

Capps repeatedly attacked Williams for taking $62,000 in campaign donations from the cannabis industry over the past two years, just under $14,000 in the months right before the supervisors adopted the county’s cannabis ordinance. Capps termed Williams “a one-issue supervisor,” and held him responsible for what she termed the “most lenient regulations” in the state when it comes to cannabis. (Williams was one of two members of the board’s cannabis subcommittee and one of four votes in favor of the ordinance.) The supervisors, Capps charged, have been forced to spend an inordinate amount of time on cannabis in the past year, 15 times more than on homelessness, she claimed, and six times more than on housing.

“Are you on the side of the special interests or are you on the side of the people?” Capps demanded. “We need to curb the role of money in elections.”

Williams, now running for reelection after one term as supervisor, did not directly return Capps’s fire but instead sought to humanize himself. He described himself as a “very peculiar young kid” when growing up in Isla Vista — “very strange” — because he found himself so precociously fixated on issues of environmental protection and social justice at such a young age. In Williams’s 17 years in office — he served first on Santa Barbara City Council and later in the State Assembly — Williams stressed that he’s always stayed “faithful” to issues such as climate change, emergency preparedness, and income inequality, citing a number of actions taken by the board of supervisors.

Williams quibbled with the $62,000 figure cited by Capps, arguing that one of the alleged cannabis donors, Peter Sperling, was not actually involved in the cannabis industry, though Sperling’s father had, in fact, helped underwrite California’s ballot measure to legalize medicinal marijuana almost 20 years ago. Williams dismissed the cannabis donations at one point as “chump change,” insisting the contributions hadn’t “swayed” his position in the least.

Williams acknowledged that the new industry had inflicted unforeseen growing pains but said that county enforcement teams had raided no fewer than 59 cannabis operations in the past 16 months. That, he argued, hardly qualified as “preferential treatment,” insisting that if he were forced to acknowledge numerous “mea culpas” about cannabis, then he should be given credit for cracking down on the industry.

About 150 people showed up to watch the debate, moderated by political blogger and columnist Jerry Roberts and Independent reporter Delaney Smith. When Smith pressed Capps about a million-dollar shortfall in the school district’s free food program — a cause Capps has loudly championed — Capps highlighted how she was acknowledging the problem and not blaming previous school boards or the state legislature, as she intimated Williams has done at various times over cannabis.

Capps blasted away at “the influence of special interests,” arguing that the county — a $1 billion enterprise — should have studied the economic hardship the new industry might impose on wine grapes and avocado ranchers in terms of terpenes and pesticides before allowing the new industry to launch. The failure to do so, she said, is costing avocado growers tens of thousands of dollars and subjecting the “little lungs” of grade school kids to the uncertain impacts caused by exposure to cannabis fumes.

Capps also blasted the county’s failure to collect tax revenues from 60 percent of the county’s cannabis operations. Williams retorted that many of the nonpayers had been shut down by enforcement raids.

While Williams is now declining to accept contributions from cannabis growers, Capps pointed out the emergence of a new political action committee, suggesting it was designed to offer a spigot for cannabis dollars. When Williams suggested that another political action committee might have been created to help Capps, she quickly retorted, “That’s hogwash.”

On issues like homelessness and poverty, Williams said the test was not how much time the supervisors devoted but how much money they spent. The county, he said, had helped create 800 units of permanent supportive housing throughout the county to help deal with homelessness. Capps noted that one out of eight students in the Santa Barbara Unified School District qualified as homeless.

On climate change, Williams highlighted how hard he’s pushed the county’s new “community choice” program, giving electricity customers the ability to purchase 100 percent renewable energy. Capps in turn highlighted her efforts at the school board to equip district properties with solar panels and micro grids.

Capps, whose mother and father both represented Santa Barbara in Congress, hails from the South Coast equivalent of political royalty, a perception that both helps and hurts. She stressed her hometown roots. Even though she left town for 20 years to work as a speech writer and communications specialist for the likes of Senator Ted Kennedy and President Bill Clinton’s White House, she was born and raised in the 1st District, where she’d moved back.

Both Williams and Capps are formidable candidates, representing different wings of the Democratic Party. As is often the case when like-minded candidates clash, the campaign has been unusually tough and bruising. Capps stressed there was nothing personal about it.

“I like Das as a person,” she said. “He’s a good dad.”