Santa Barbara Observes Black History Month

From Alabama to State Street, Santa Barbarans Look Back and Ahead

By Brian Tanguay | Published February 6, 2020

Santa Barbara Observes Black History Month

From Alabama to State Street, Santa Barbarans Look Back and Ahead

By Brian Tanguay | Published February 6, 2020

In December 2019, I was in the Deep South for the first time in my life. I came from California, bluest of the blue states, to Alabama, one of the reddest of the red. I came because after watching the HBO documentary True Justice several months earlier, I felt compelled to visit Montgomery, Alabama. Before the credits had stopped rolling, I knew I had to see the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice created by Bryan Stevenson, the subject of the film. Stevenson is the founder of the offices of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), which provides legal services to the poor, to children being tried and incarcerated as adults, and to inmates on death row.

Montgomery celebrated its bicentennial in 2019. Situated in the southeastern part of the state near the Alabama River, the city became the state capital in 1846. The telegram ordering Confederate troops to fire on Fort Sumter, sparking the Civil War, was dispatched from Montgomery. The first White House of the Confederate States of America was established there and still stands across from the state capitol building. Montgomery is also considered the birthplace of the modern civil rights movement, the turbulent and bloody period from 1954 when the Supreme Court of the United States outlawed school segregation to the April morning in 1968 when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in Memphis.

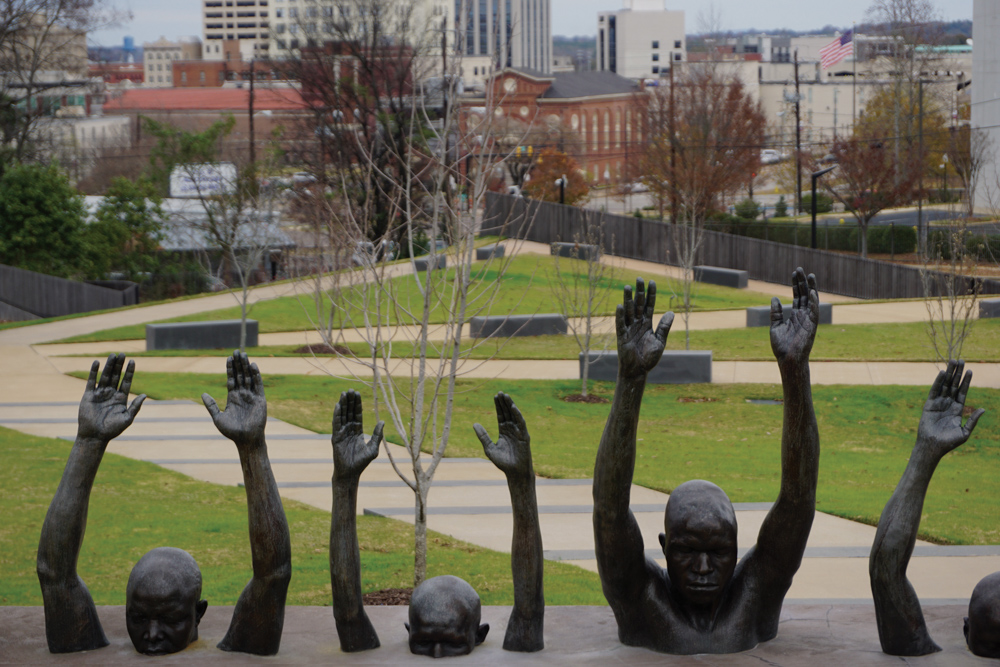

Kwame Akoto-Bamfo’s sculpture depicting the transatlantic slave trade. | Gabriel Tanguay Photos

Downtown is dotted with historical markers that tell Montgomery’s story. When the Civil War began, Alabama had one of the largest slave populations in America for two reasons. One, Congress had banned the importation of slaves from Africa in 1808, shutting off supply from that continent. But the 1803 Louisiana Purchase added thousands of square miles of land to the U.S., much of which was cleared for cotton cultivation. As a result, slaves from upper southern states were relocated, many of them to Alabama. Two, cotton was the most important commodity in the world at that time, and Alabama had particularly fertile soil in which to grow the plant. Cotton was the raw fuel of the Industrial Revolution, and the demand for the fiber from mills in England drove an incessant and urgent need for slave labor in America. With enough land and enough slaves, a planter could make a fortune. Montgomery was a key hub in this trade. In half a century, slave traders moved thousands of people from the Upper South to the Lower South, swelling Alabama’s slave population from fewer than 40,000 to more than 400,000.

The enslaved came south by foot at first, driven like livestock from Maryland, Virginia, South Carolina, and Kentucky, but this method was slow and expensive. Two new modes of transportation, the steamboat and the railroad, made moving slaves to the cotton camps easier and faster. Once rail lines — built by slave labor — connected Montgomery to other points, slaves began arriving by the hundreds.

Connective Tissue

The Legacy Museum, a creation of the EJI, opened in 2018. It is like connective tissue that links the past and present of not only Montgomery but also the United States, as it presents the history of slavery, Jim Crow segregation, racial terrorism, and mass incarceration through videography, photographs, documents, interactive maps, art pieces, news footage, and first-person accounts. The museum occupies the site of a former warehouse where enslaved people were held until they were sold.

As visitors approach the padlocked wooden door, a hologram of an enslaved person appears and tells his or her story. First, a woman, desperate for news of her children, speaks of listening in vain for the sound of their voices. She likely will never see their faces again. Then, a man who has been sold more than once talks about being handed to a new master and transported to unknown territory, far from his wife and children. He has no say in the matter, no right to protest, no authority to petition. He’s a tool of his owner, as valuable as the amount of cotton he can pick per day. But he’s also human capital, a liquid asset that can be sold or mortgaged if his owner falls on hard times and needs cash. The most heartrending story is told by a small boy and his younger sister in a single plaintive, unheard call in the darkness for their mother.

Of all the exhibits in the Legacy Museum, there were two that drove the reality of racial injustice home. The first was an exhibit of 19th-century newspaper advertisements listing the names, ages, sexes, skills, and dispositions of slaves to be auctioned. These were so matter of fact, so mundane and ordinary; buying a slave was hardly different from buying a bolt of cloth or a sack of flour. If the slave on offer was female, the buyer could lift her rough cloth dress and inspect the width of her hips for child-bearing potential. He could force her mouth open and examine her teeth. He could fondle her breasts if he felt like it. She had no more standing than a cow or a goat. On auction day, slaves were washed and combed, dressed in their cleanest clothes, had their skin burnished with oil, and were warned by traders to make a good impression on potential buyers. The whip waited for those that refused to cooperate.

The second involves sitting in front of a Plexiglass window and lifting a black telephone from its hook. Highlighted in this exhibit is the disproportionate number of African-American inmates — who are often charged the maximum sentence due to poor defense representation — in the penal system. Once you put the phone to your ear, an incarcerated person appears before you and begins talking, and the person looks and sounds so real that you feel you are in the visitors’ center of a prison. Every detail is perfect. It’s hard to believe you’re not looking at a living being, listening to the story of how they came to be here and what they endure on their side of the glass. Women and men, young and aging.

But the Legacy Museum’s story is really this: Slavery didn’t end when President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 or when the Confederacy surrendered. It has evolved since the Civil War, adopted new guises such as convict leasing and rigid Jim Crow segregation in the early 20th century to keep black people in bondage or second-class status. This deliberate transformation was aided by the decisions and actions of the United States Supreme Court, state legislatures, county courts, churches, all-white juries, white citizen councils, and police.

A Moment of Silence

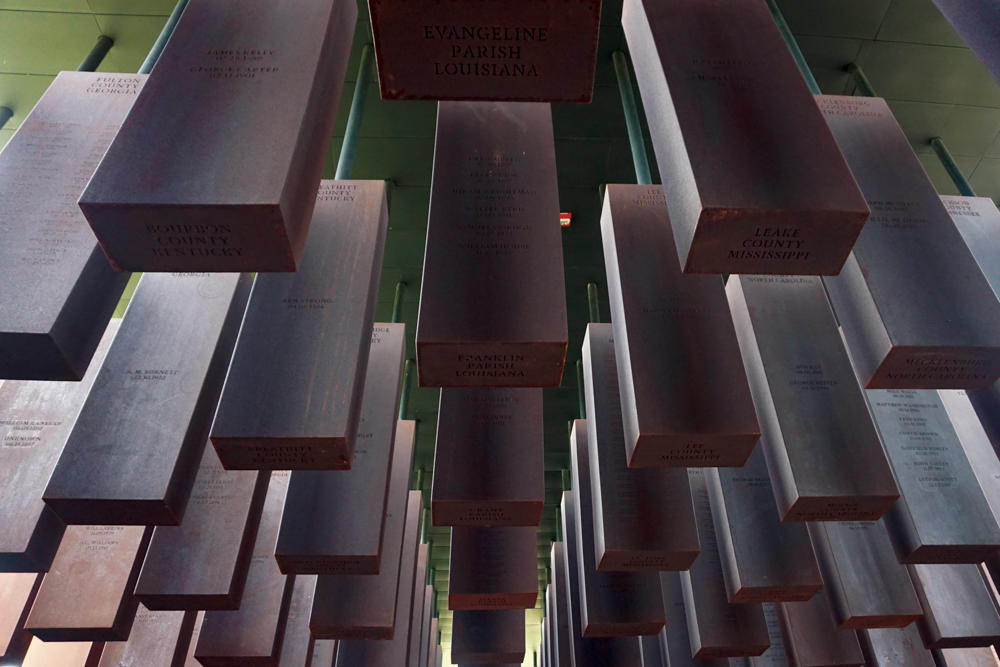

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, companion to the Legacy Museum, sits on six acres overlooking downtown Montgomery. From Reconstruction to the middle of the 20th century, more than 4,000 black people across the South were lynched. The true number is likely higher. The names of these victims of racial violence, meticulously researched and documented by the EJI, are engraved on more than 800 corten steel monuments, one for each county where a lynching occurred.

Taking the monuments in was initially overwhelming — name after name, date after date, county after county. John Cherry. Bernice Raspberry. Jesse Payne. Alma House. These were human beings with individual stories, children, brothers and sisters, parents and grandparents, who had their lives stolen from them because of the color of their skin. They were lynched to spread terror in the black community, to keep former slaves and their descendants in their assigned place at the back door.

Walking the grounds — from the installation by the Ghanaian sculptor Kwame Akoto-Bamfo depicting the transatlantic slave trade (six slaves bound by chains, faces frozen in bewilderment or anguish) to three statues of black women striding purposefully during the Montgomery bus boycott to the words of Toni Morrison etched in marble to the Ida B. Wells Memorial Grove — left me feeling a profound sense of sadness. There was no turning away from the fact that this campaign of racial terror happened; the proof was all around me, in the metal monuments bearing names and dates and counties, and in hundreds of clear glass jars filled with soil from sites where lynchings occurred.

The work of the EJI, the Legacy Museum, and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, is about confronting our history. It seems to me that most Americans are not interested in the hard, painful work of racial reconciliation. Our political current is moving in the opposite direction, flowing back toward intolerance, fear and hatred of people who have darker skins or strange-sounding names, who speak a different language or who worship a God we don’t agree with. Some argue that slavery and Jim Crow happened long ago; they say it’s different now and we should just move on. In many respects, it’s different now. But the point of the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is to show how a line can be drawn from 1619, when the first slaves landed in Jamestown, to 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri, where Michael Brown was shot and killed by a white police officer who escaped prosecution. The line connects the enslaved man stolen from Maryland in 1834 and transported to a labor camp in Alabama to the Watts uprising in Los Angeles in 1965. We see the line when state governments gerrymander congressional districts to dilute the political strength of African-American communities and erect barriers to dissuade and discourage African-Americans from exercising their right to vote, and we see it again when black people are incarcerated at a rate completely at odds with their percentage of the total population. Searching below the surface for root causes is necessarily hard work that few people are willing to do.

As I stood at the memorial, looking down at Montgomery, I was struck by the profound faith and hope this space represented. The Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice profess the hope that we can learn from the past and avoid repeating its mistakes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.