“It’s barely my third quarter at UCSB. I have had 5 friends leave already. They were all minorities. UCSB is too expensive, complex, and inaccessible to students who didn’t have a good high school education … no one should leave a college because they can’t afford it or because they don’t feel included or welcomed. UCSB caters to the privileged.” —@”LesleyH”

After scrolling through my Twitter feed, my heart sank upon reading a narrative I know all too well. Lesley managed to summarize in a 140-character post all my complex feelings about being at a competitive four-year institution. She was a first year like me, and a woman of color in STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) who was also trying to navigate this campus. I had already heard about friends of friends dropping out of college because of just how expensive and emotionally taxing it can be — especially for students who come from my background. And we are not exceptions — 18- to 24-year-olds in America today have among the highest rates of poverty of any age group, according to a 2019 study by the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

The whole point of going to college is to enrich your mind, learn new things, and succeed in the subjects you have chosen to pursue; however, academics cannot be the focus of students when they are struggling to manage their most basic needs. Think tanks and academics who research these issues have called attention to why there is a growing divide in educational opportunities between low-income and first-generation students and their peers. It is imperative that we listen to and elevate the voices of the students who are living this truth.

I was grateful to have a single mother who gave everything she had to give me a better life in this country. I was incredibly lucky to attend a high school where practically every student was college bound. However, being low-income meant that I was not going to have a private college counselor, SAT tutors, or parents who could secure my spot by writing a hefty check to admissions counselors. My dedication and ambition were the only two things I had to get me there.

And even after I made it to a four-year university, at times my hard work didn’t feel sufficient to stop me from feeling out of place, despite being a high achieving alum from a competitive International Baccalaureate program. The imposter syndrome would creep up in lecture halls and during office hours. Any mistake I made felt like proof that I didn’t belong and should have chosen a different career path, major, or school.

Most students are likely to feel a sense of inadequacy in their freshman year. However, for first-generation and low-income students, the lack the access to resources — such as the means to pay for textbooks or laptops, which their peers take for granted — adds to that uncomfortable feeling. At times it feels like we’re always a few steps behind our peers before we’ve really begun our academic journey.

It’s a combination of the little things — our anxiety about our lack of money and our worries that we’re underperforming in our classes — that contributes to a bigger fear that maybe we don’t belong in higher education. And because of this, many students drop out. It is with an underlying seriousness that my friends and I make jokes about dropping out because we wonder whether the cost is actually worth all the stress. For some, it becomes an unfortunate reality; withdrawing from a university that is “too expensive, complex, and inaccessible,” as Lesley put it, feels like their only option.

I can’t deny the incredible resources that my university offers for low-income and first-generation students. We have programs that want to help us navigate college as successfully as possible, have tutors and mentors, and manage our limited finances — and our stress. But there is only so much that these programs can do to address larger, more systemic issues of the education system that center around class. Those issues begin with the cost of higher education itself.

We have a problem in our system when college students have to choose between purchasing food or purchasing books. Fully 43 percent of us feel compelled to skip meals to save for books. We have a problem in our system when students resort to leaving a major they were once so passionate about because the additional fees became impossible to pay on top of their other expenses. We have a problem in our system when poor students are working close to 40 hours a week, at a job that has nothing to do with their field of interest, while still attending school full time.

Among low-income student workers who work 15 or more hours a week, 59 percent have a C average or lower. The disappointment, the anxiety, the sheer feeling of fatigue: It all leads to a decline in mental health that, of course, further affects academic performance. How can we expect students to excel in their classes, or pass their classes, or even graduate on time when they are preoccupied with making ends meet? At the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2017, the academic probation rate was 17 percent for first-generation students compared to a rate of 11 percent for the general population. There was almost a 10-point difference in the graduation rates of first-generation students and the rest of the school’s population.

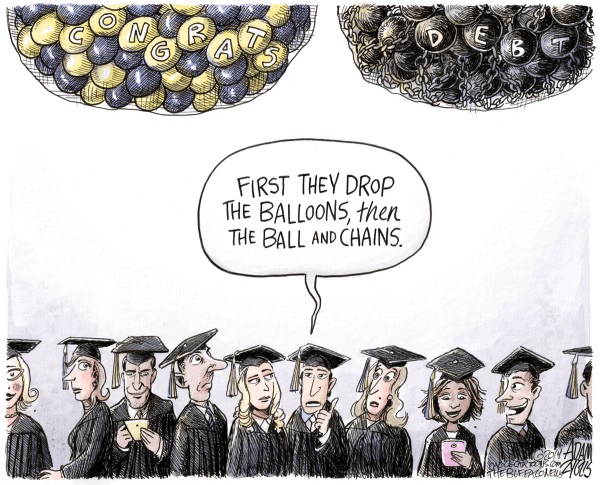

The inequalities within our institutions that prevent certain students from being able to succeed to the best of their abilities can no longer go ignored. That goes without saying. The full public funding of what is now an extremely expensive university system would make education more accessible to a wider demographic of students and eliminate the crippling issue of student debt.

I am no expert in public policy, nor in economics, but I am a first-hand witness to how this burden is affecting students. I don’t have all the answers either, but I know that the existing system is not acceptable. We can and must do better for our students, particularly our marginalized, low-income, and first-generation students. Though workshops and support from individual programs help, these are only temporary solutions to help students manage their time and expectations; they do not remove the source of student stress.

The universities cannot solve this problem alone. What we need is a broader public commitment to making higher education accessible for all. We the people have to invest in our students. The median family household would only have to contribute $66 or less to fund tuition-free public universities in the State of California, according to a policy report by university professors, including Professor Christopher Newfield of UC Santa Barbara, who frequently writes about the need to reform the public university system. Over 70 percent of Americans believe that public spending on higher education is an excellent or good investment overall, as it benefits individuals and society as a whole.

If Americans truly believe that higher education is one of the best investments the public can make, then it’s time to put our money where our mouths are. After all, isn’t a brighter future for all our students worth it?