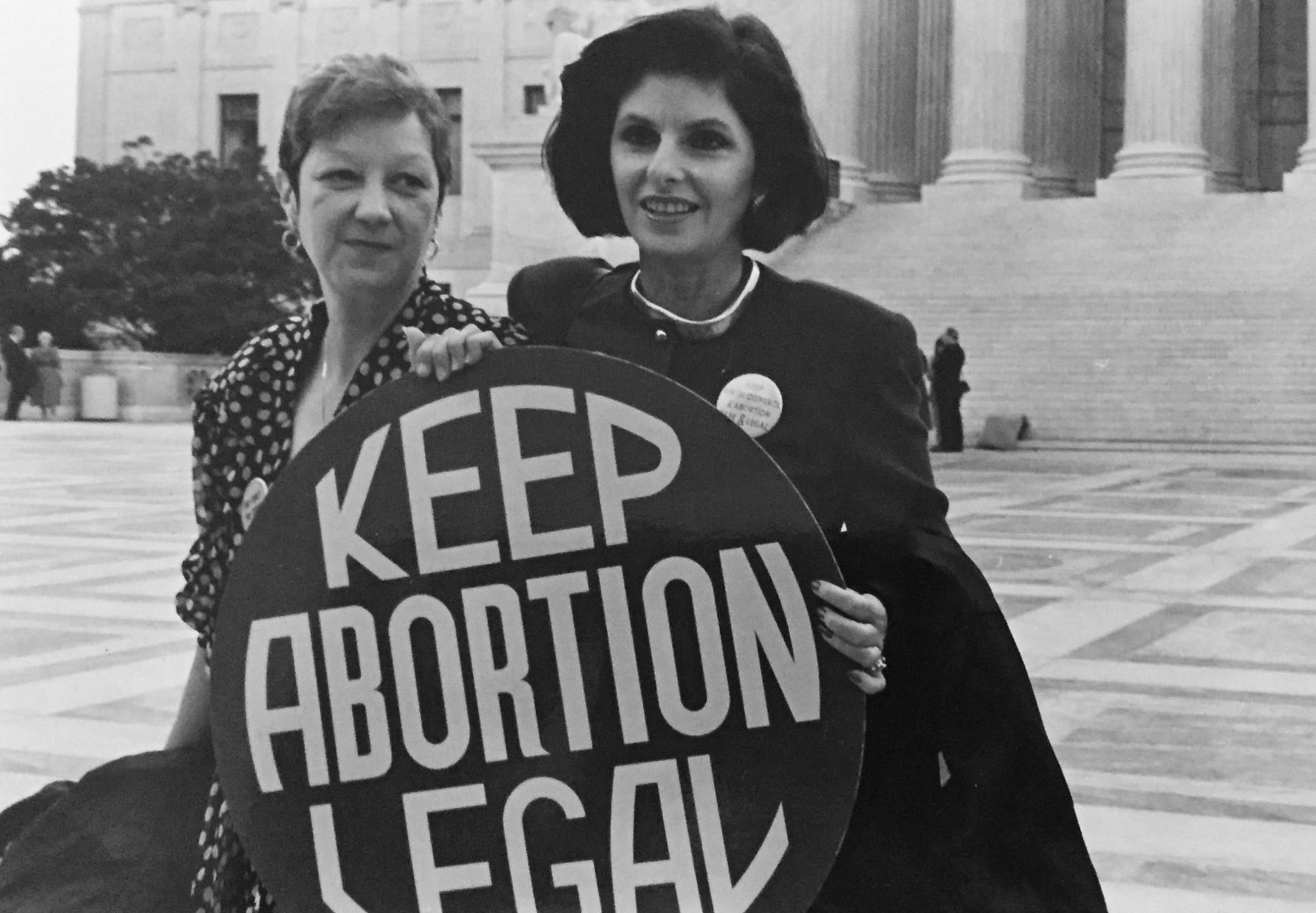

Threats to Roe v. Wade

Fighting for the Right to Make Decisions About Your Own Body

As the 47th anniversary of Roe v. Wade approaches on January 22, our attention should be directed toward maintaining and enhancing reproductive and sexual health care that best addresses the needs of diverse people. Anti-abortion movement advocates and politicians anticipated the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion, and the movement has successfully worked to create obstacles to both abortion care and contraception.

Roe itself, often shorthanded as providing “the right to choose,” faces significant threats. But reflecting on how we arrived at the current state of reproductive policy reveals that the crisis of access to reproductive care is widespread and experienced unequally. According to the Guttmacher Institute, an “unprecedented wave of bans” on abortion in 2019 resulted in 25 new laws, mainly in the South and Midwest. I advocate for defending Roe and intervening in the policies and practices that continue to erode this landmark decision and intentionally institute reproductive inequalities.

Historically in the U.S., reproductive- and sexual-health-care policies have been shaped by social, political, and legal contests over gender, class, race, sexuality, immigration, and religion. Abortion care may be legal, but for many women and girls, it is effectively inaccessible.

Some barriers have high media visibility, such as the 2003 federal law prohibiting a medical abortion-care procedure when then-President George W. Bush approved the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act. Also highlighted were the bombing of abortion clinics, the murder of doctors and clinic workers, and the installment of anti-abortion U.S. Supreme Court judges. But innumerable low-visibility practices and policies in many states curtailed abortion-care access, including a lack of abortion-care providers in many regions, insurance bans, government-mandated waiting periods, and medical procedure limitations. Low-income women and women of color are most affected by these constraints and have fewer resources to work around them.

A range of federal funding restrictions contribute to unequal access to reproductive information and care. The Global Gag Rule, established in 1984 as the Mexico City Policy, prohibits U.S. funding for organizations that provide or even discuss abortion. This logic is now applied within the U.S. to restrict Title X funding. The nonprofit Planned Parenthood and other holistic reproductive-care providers have turned down this federal funding to avoid complying with the silencing of abortion-care information. By so doing, they provide safe, legal, low-cost reproductive care.

Federal bans on Medicaid funding for abortion care, with exceptions to save the life of the pregnant woman or in cases of rape and incest, were established by the 1976 Hyde Amendment and are reenacted annually. The amendment also applies to women in the military, Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, federal prisoners, and Peace Corps employees, and it is meant to shrink the reach of Roe. A movement to repeal the Hyde Amendment has been led by women of color for decades, and in 2016, the Democratic National Committee Platform supported it. This is expected to be featured during the 2020 presidential election.

This is a critical time to resist policies that restrict reproductive options. Public health decision-makers, voters, and everyday women and girls, by joining coalitions, can raise their voices. Legal collaboration can look like the multistate coalition of 22 attorneys general, including California’s Xavier Becerra, who filed a December 2019 amicus brief in the U.S. Supreme Court. They support a constitutional challenge to a Louisiana law that requires abortion care providers to have local hospital admitting privileges; an identical Texas law was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2016.

Collaboration for women’s rights is also supported by reproductive justice advocates. The SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective defines reproductive justice as the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities. This framework requires that equitable policies be built by working from the grassroots with those who have the least access to reproductive health care. The Intersection of Our Lives, formed by the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health; In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda; and National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum found in a 2019 poll that “84 percent of women of color voters believe that candidates should support women making their own decisions about their reproductive health.”

Reproductive justice, as a theory, strategy, and set of practices, acknowledges the decisions that women, men, gender nonbinary, and transgender individuals make about their bodies and lives, setting their options within families and communities. This framework mobilizes us to focus on how power operates: U.S. policies have not applied evenly to all people, and appeals to “choice” do not reach the majority of low-income women and women of color or address the disparities in our society.

Activists for reproductive justice, in coalition with allies, provide dynamic ways to enhance our reproductive rights and health. The personal and political stakes are high, and there are many ways to raise awareness of the threats to women’s rights and support reproductive justice. March, protest, lobby, educate, collaborate, and, above all, vote.

Laury Oaks chairs UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Feminist Studies.