When Todd Ryckman got his hands on one of the first-ever iPads that came out in 2010, he immediately knew they would change the world.

Ryckman was an AVID teacher at Dos Pueblos High School at the time, where he secured site funds to pay for iPads in his 10th-grade class. He allowed the students to pay a small monthly sum so that they could own their iPad by the time that they went off to college. At the center of Ryckman’s vision was equity.

“It just hit me that my own kids have such an advantage over kids without devices,” Ryckman said. “I could see the digital divide.”

About 58 percent of Santa Barbara Unified School District’s students are low income. Many of them would likely be more academically disadvantaged without the district’s one-to-one program.

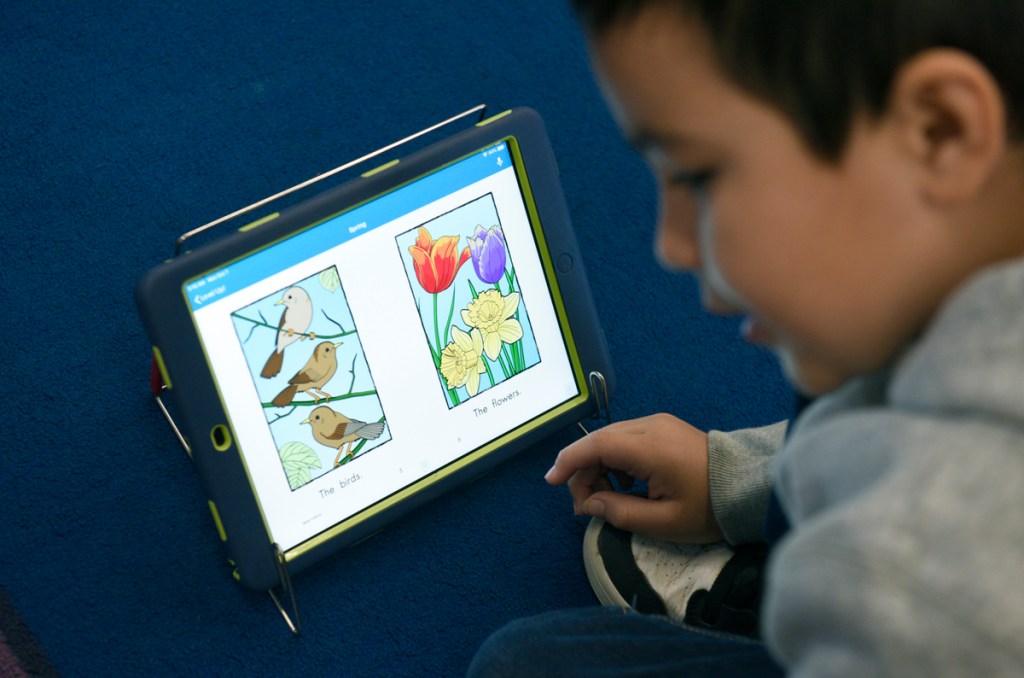

The program, now branded as techEQUITY, is in its second year of full deployment across the district. It puts an iPad in the hands of every single 4th through 12th grade student district-wide. They are able to take it home and use it for school work and bring it back to take into the classroom as a tool for learning.

“We stopped doing big take-home science projects and things like that,” said Robert Cooper, a sixth-grade teacher at Adams Elementary. “We already knew what to expect. There are going to be some projects that are much more expensive and nice looking, and some much less so, because of what the kids have at home. It just wasn’t fair.”

The techEQUITY program began as a pilot in the 2012/2013 school year — at Adams, Franklin, and Washington elementary schools, and La Cuesta high school — one year after Ryckman was promoted from his teaching position at Dos Pueblos to the district’s director of technology. It was highly successful at those schools, mainly because of one key factor Ryckman insisted upon: Teachers receive iPads first.

Ryckman put together a team of teachers from the district, including Adams’s Robert Cooper, to work as “tech coaches” and train teachers to use the iPads in the classroom for a full year before rolling it out to the students in the techEQUITY program. Ryckman attributed Los Angeles Unified’s failed attempt to execute the same one-to-one iPad to the fact their students received the iPads before the teachers did.

Teachers at all grade levels have said the integrated technology in lessons has revolutionized the way they teach.

“I’m a firm believer that kids don’t need me to tell them the quadratic equation because they can google it,” said Gina Pearce, a pre-calculus teacher at Dos Pueblos High School and a tech coach on Ryckman and Cooper’s team. “They use the iPads to google those sorts of questions at home, so we can use our face-to-face time in class for meaningful instruction.”

Pearce said she records videos of her lectures, which is helpful to the students because they can pause and rewind until they are comfortable with the material. She said she often sees her students rewatching her videos to refresh their minds before a test. Her method leaves her more available to give one-on-one instruction to those who are most struggling in her class, while the ones who understand can use the iPad in the meantime.

As iPads went home, it became clear that they bridged the digital divide for more than just the students. They began to tell a story about the families in Santa Barbara’s district. One of the most commonly downloaded apps on the devices has been MoneyGram, Ryckman said, which many Latino parents use to send money back home.

The district is 60 percent Latino overall, and its nine elementary schools are 73 percent Latino. The MoneyGram app speaks volumes — for many families, the device their child brings home as part of the teachEQUITY program is the only device in the household. Another common use, Ryckman said, is parents using the iPad to take English classes online from Santa Barbara City College.

“The internet is unlimited, and textbooks are beginning to go away,” Ryckman said. “Open educational resources are free online, but if everyone doesn’t get access, the achievement gap will widen further.”

The system he used back in 2012 that allowed high school students to give small monthly payments to eventually own their device for college was imitated by Apple as a model for its program Invest for Learning (IFL), in which about 40 percent of Santa Barbara families participated during the initial district pilot programs. Apple’s company stopped managing the program, so Ryckman’s team recreated it as the techEQUITY Partnership Program, so students can continue to have access to a device after they leave the district.

Ryckman is making a presentation to the school board Tuesday night because the techEQUITY program needs an upgrade now that it’s district-wide. He said the district’s server is one of the largest and most sophisticated networks in Santa Barbara County, second only to UCSB’s. At its peak, he said, there are up to 10,000 users and 20,000 devices on the network at any given time. Teachers and students need to be able to depend on the district’s network, he said, and classroom learning may suffer without a reliable network.

“My goal is for someone to walk into a classroom and not even notice the devices,” Ryckman said. “Nobody looks twice at students holding a pen and paper. It should be the same thing.”

The school board will meet to hear his presentation at 6 p.m. Tuesday, December 17, at 720 Santa Barbara Street.