As the plane approached La Guardia airport, I looked down on the sparkling skyscrapers of Manhattan, but in my mind there was a dark void. For the first time in more than a dozen visits to New York City, I would not be greeted by a big hug from Donn Bernstein.

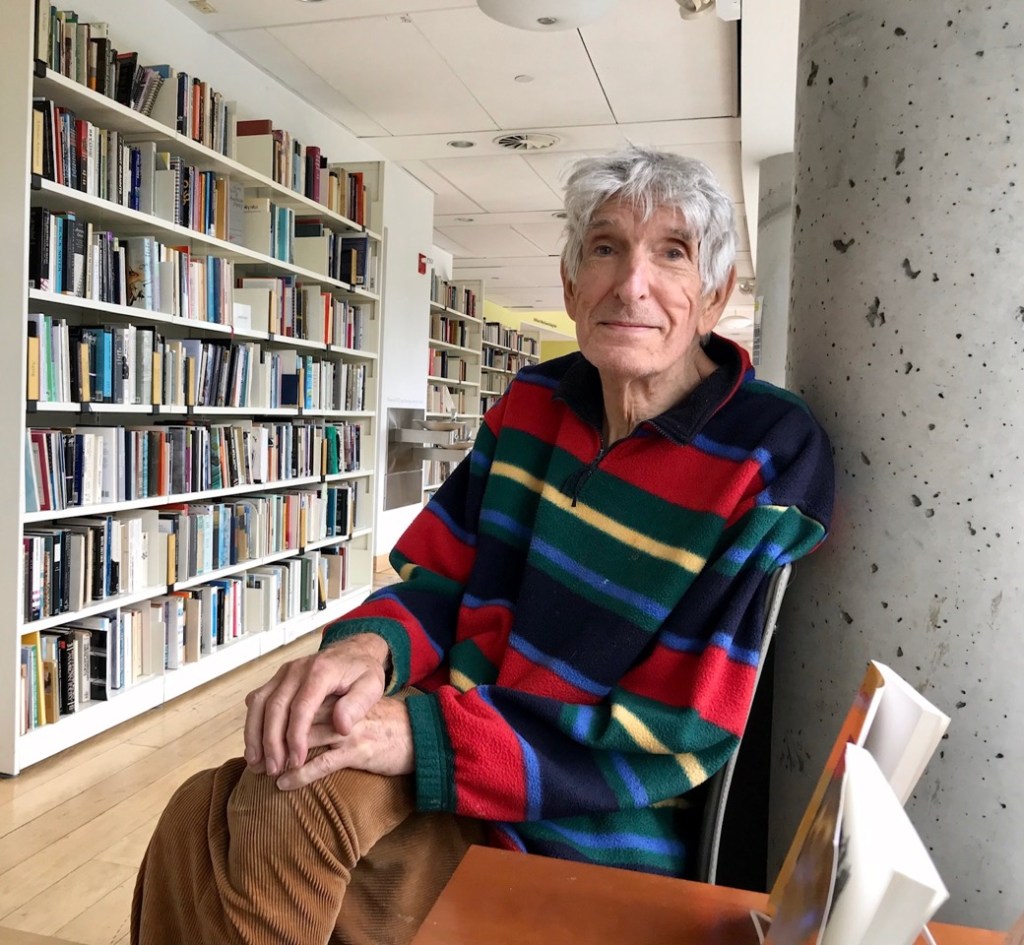

Bernie, or Double-N to his spell-checking friends, was a blazing force of good human nature. His boisterous personality, projected by a booming voice, might have scared the daylights out of you upon an initial encounter, but inevitably you would warm up to his spirited presence, and often become his friend for life.

His was a sportswriter and publicist by profession. He started as a newspaper reporter in Berkeley and his native San Francisco. College football was his favorite beat, and that brought him to Santa Barbara in 1964, when UCSB hired former Stanford coach “Cactus Jack” Curtice and brought in Bernie as the school’s first sports information director (SID).

When UCSB dropped its financially draining football program after the 1971 season, Bernie went big-time as SID for the Washington Huskies. After three years in Seattle, he was hired by ABC, the leading sports network, to be its director of media relations for NCAA football. That took him to New York. He spent the rest of his life there, migrating to Cohn & Wolfe, a global ad agency, after the ABC sports empire was broken up.

Although the hustle and bustle of the Big Apple were ideally suited for Bernie, he left a big piece of his heart in Santa Barbara. He often came back to visit UCSB, which made him an honorary alumnus and enshrined him in the Gaucho Athletic Hall of Fame. He had purchased his first home in Isla Vista, a ramshackle dwelling above the seashore on Del Playa Drive that he called “The Cabin,” and he retained ownership for years after moving out. It was there he hosted Bernie’s Bicentennial Bash in 1976. It was a party to end all Fourth of July parties.

In New York, Bernie would celebrate birthdays and other occasions at McSorley’s Old Ale House, the city’s oldest saloon, founded in 1854. It is ruled by a slogan mounted on the wall: “Be Good or Be Gone.” There are just two choices from the bar: light ale or dark ale. Bernie composed poems as a hobby. He was no W.B. Yeats, but he did show a flair in his ode to McSorley’s:

Where the ghosts grovel, gulp

and glare,

Where we were drawn to drink and dare;

Where history swirled and timelessness twirled

And where camaraderie unfailingly unfurled.

Where the waiter’s brogue was

deep and heavy

While delivering mugs by the bevy;

Lingering echoes of incessant barks:

“30 lights … and 30 darks.”

When he was gone, Bernie told his friends, his only wish was to have them hoist a mug in his memory at McSorley’s. After he died on October 16, word got out that there would be such a gathering on November 7. So there I was, with some 100 other people who could make it, all with a special connection to Bernie.

They came with stories to tell from all phases of his life. Gaucho football players from the 1960s showed up. Several former UCSB students whom he had helped professionally were in the crowd. I was one of them.

I met Bernie shortly after he arrived at UCSB in 1964, when I was starting fall practice with the freshman track team. He had a pat on the back and a handshake for all the athletes in the locker room. Later I saw him at work behind an open window in his tiny Robertson Gym office that he called his coke stand. Therein he pounded furiously on a typewriter, cranked press releases out of a ditto machine, and raised hell on the telephone in a voice that carried across the campus. He was one of my inspirations when I tried my hand at sports writing for the UCSB yearbook.

Flash ahead to my graduation in 1968 with a degree in anthropology. The summer went by, and I had no job, no idea about my future. My brother needed a ride to UCSB for the start of the fall quarter, and just before I was going to drive back to Los Angeles, I ran into Bernie. Minutes after he inquired about my situation, he called News-Press sports editor Phil Patton, who was looking for somebody to cover high school sports. I had an interview two days later and soon began a 38-year career at the paper.

Bernie’s own career took off at ABC. He had shown his chops when the Green Bay Packers spent a week training at UCSB before Super Bowl I in 1967, and he helped coach Vince Lombardi and the team with their press relations. At all the big games ABC exclusively covered — USC-Notre Dame, Ohio State-Michigan, Texas-Oklahoma, Alabama-Tennessee — Bernie was the guy behind the scenes, setting up interviews and preparing Keith Jackson and other announcers for their jobs. Network television was extremely competitive, rampant with high-strung egos, but everybody got along with Bernie.

It was fitting that when Bernie was at UCSB, he met Phil Womble, a young man with cerebral palsy who was interested in sports, and brought him into the Gaucho athletic family. Womble was an inspirational fan of the Gauchos for the rest of his life. Whenever Bernie visited Santa Barbara, his first stop was Womble’s apartment. In 2006, the three of us celebrated a 200th birthday party at Elings Park. Bernie and Phil were 70, and I was 60 — the only one who survives today, with both of them in my heart.

At Cohn & Wolfe, Bernie handled various sports promotions. Duane Freeman was 19 when he went to work for the firm, a trepidatious African-American in a starchy milieu. Bernie welcomed him aboard. “He took me under his wing,” Freeman told me at McSorley’s. “He was the sweetest man, one of a kind. I loved him like a brother for 20 years.”

As he advanced in his seventies, Bernie was expected to retire. But Freeman, an office manager, took him under his own wing. “I said he can sit with me, we’re good,” Freeman said. “I love hanging with the dude.” Bernie produced an in-house newsletter before finally retiring at 80 three years ago.

Bernie lived in a prime Manhattan location, 78th and Columbus. He was rarely alone, because old and new friends kept showing up. Engaging in conversation was his favorite pastime: “Let me say this about that….” My wife called him “the Jesus of the Upper West Side.” The late Beano Cook, an ABC colleague, often joked: “Bernstein’s wife will be the first woman ever to die from listening.”

Bernie was too involved with too many people ever to take a wife. That deficiency meant that his kitchen was unexplored, but he did take care of his abode. Every spring, Bernie planted flowers outside his door and lovingly tended them. He moved to a place with patio two years ago and created a virtual botanical garden. In one of the flower boxes, a dove hatched a pair of eggs. Bernie named the babies Scrambled and Omelet. He was saddened when their mother fled, and they did not survive.

Bernie had his own battles for survival over the last four decades of his life.

First quarter:He was accosted at his door by thugs who took him inside and beat him viciously with a poker. They wrongly assumed he had a safe full of riches. His sense of humor came out when he told his assailants, “I’ll write you a check.”

Second quarter: Colon cancer, surgically treated, leaving him with a clean bill of health.

Third quarter: A subdermal hematoma that could have taken him out if not for his hospitality. Concerned that he did not fling open his door, visitors summoned emergency medical attention.

Fourth quarter: A serious infection and a fall that sent him to intensive care. There was a period of recovery, but then, on fourth and goal, he boldly went for it. He got up and took another fall.

In his last act of generosity, Bernie had arranged for his body to be donated to Cornell University for medical science.

His spirit hung in the air at McSorley’s as dozens of mugs were raised in appreciation.