UC San Diego scientists sifting through nearly 200 years of Santa Barbara Channel sediment discovered an “explosion” of plastic pollution after World War II, according to a study published in the journal Science Advances. Core samples dating back to 1834 revealed that the amount of microscopic plastics in the channel doubled about every 15 years since the 1940s. “Our love of plastic is actually being left behind in our fossil record,” said lead biologist Jennifer Brandon in a press statement.

Brandon’s team chose to study the Santa Barbara Channel because of its relatively still waters and a near total absence of oxygen at the seafloor. They picked a spot to drill a few miles offshore and 1,900 feet down. Each half centimeter of core sample represented roughly two years of human history. Most plastics were invented in the 1920s but not used in significant commercial quantities until after WWII. Brandon said their new discovery supports the idea of using plastic accumulation as a defining point of the Anthropocene, a proposed new geological epoch marked by humanity’s effect on Earth.

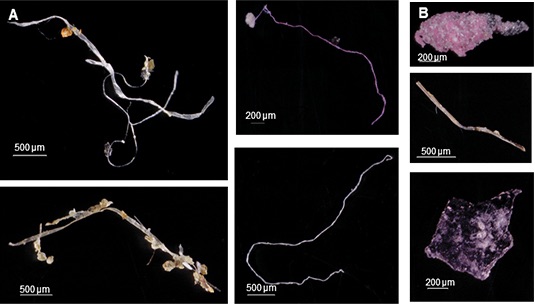

Brandon said the majority of the microplastics they discovered were in the form of clothing fibers and were smaller than a piece of lint. Much of it was likely carried to the ocean in storm runoff or discharge from wastewater treatment plants. The study didn’t analyze the effects of plastics on marine life, but the authors referenced previous research showing that ingestion of plastics by small organisms can cause physical damage that reverberates throughout the food web.

Last February, a team of Newcastle University scientists found plastic microfibers in the guts of nearly three quarters of the organisms they collected from deep-ocean basins. In April, an explorer visiting the Mariana Trench — the deepest trench in the world — found plastic bags at the bottom.