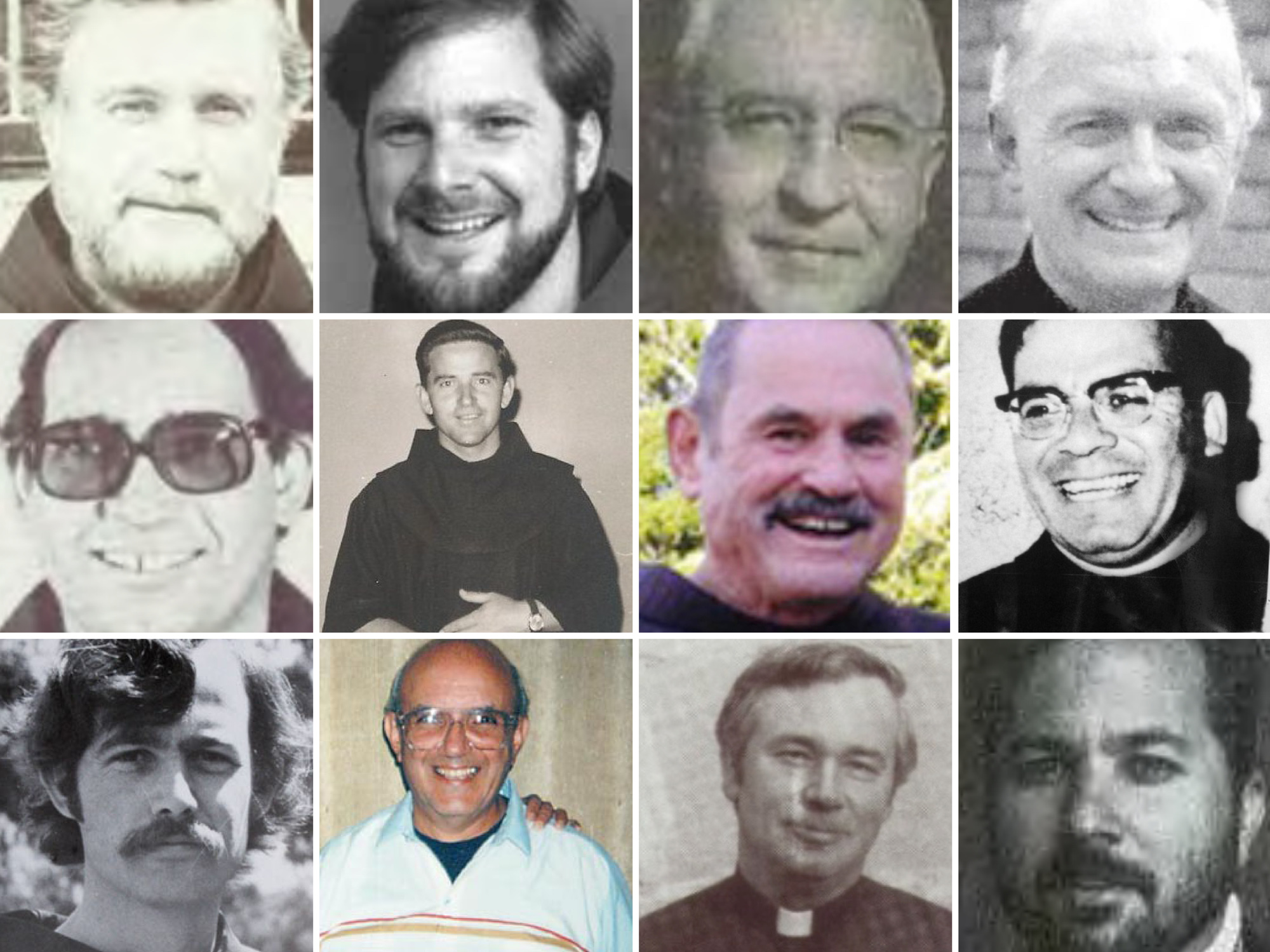

For the first time publicly, the Franciscan Friars of the Province of St. Barbara have identified 50 priests accused of sexually abusing children in its ministries since 1950. More than half — 26 — were assigned to St. Anthony’s Seminary or Old Mission Santa Barbara at some point in their careers, often after they’d been accused of molestation in another ministry, then reassigned to the Santa Barbara area.

While many of those 26 priests were previously known to attorneys, law enforcement, and victim advocates, nine names had never before been reported, according to attorney Tim Hale, who won a landmark case against the Franciscans in 2006 and has closely followed subsequent cases, as well as recent disclosures by the Catholic Church. All nine priests have died. Their names and the locations and dates of their Santa Barbara postings are as follows:

Note: These dates don’t necessarily reflect when the alleged abuse occurred, only when the accused priests were assigned here.

Camillus Cavagnaro — Old Mission Santa Barbara, 2005-2006

Philip Colloty — Old Mission Santa Barbara, 1973-1975

Adrian Furman — Old Mission Santa Barbara, 1989-2001

Martin Gates — St. Anthony’s Seminary, 1965-1966

Gus Hootka — Old Mission Santa Barbara, 1993-2006

Mark Liening — Old Mission Santa Barbara, 1941-1942, 1985

Finbar Kenneally — Old Mission Santa Barbara, 1939-1940; St. Anthony’s Seminary, 1977-1991

Felix “Raymond” Calonge — St. Anthony’s Seminary, 1965

Felipe Baldonado — Multiple CA missions (Oakland, Stockton, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and San Francisco), 1953-1964

Father David Gaa, the Province of St. Barbara’s leader, issued a statement alongside the full list, which was quietly posted on the order’s website late last Friday. “The list is being published as part of our continuous commitment to transparency and accountability,” he wrote. “We are determined to demonstrate, through this action, that we are committed to helping survivors and their families heal.”

Hale, among others, contends the release is actually a self-serving strategy by the Franciscans to preemptively shield the order from potential criminal liability after a Pennsylvania Grand Jury published a searing report against the Catholic Church last August. It was the most expansive investigation yet by a U.S. government agency of abuse within the organization. “Every Roman Catholic diocese around the country fears that Grand Jury report and what it might mean for them,” said Hale.

Last December, in a similar fashion to the Franciscans, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and the Catholic Church’s western Jesuit province self-published a list of 200 clergymen accused of child molestation, 12 of whom held lengthy postings in Santa Barbara dating back to the 1950s.

Gaa said the heightened public awareness of criminal activity within his order “came in the early 1990s from St. Anthony’s, our minor seminary in Santa Barbara. Since those early days, the friars have worked to help with the healing process for those who were abused and for the protection of children.” The order currently oversees 136 priests in ministries throughout California, Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington state. It’s headquartered in Oakland.

The order, which didn’t return calls for comment, deemed an allegation credible if there was “a preponderance of evidence that the allegation [was] more likely true than not” after an internal investigation, according to its website. Priests who’d been convicted in court or admitted to the crimes were also named. More than 120 victims were identified, the friars said. In many instances, they claimed, the accusations were made several years or decades after the alleged abuse occurred, oftentimes after the priest had died.

The list, posted in its entirety below, illuminates when certain priests were accused of molesting minors and when they were placed in Santa Barbara. Gerald Chumik, for instance, was assigned to the Santa Barbara mission in 2003 despite being accused in 1990 of forcing a boy to perform oral sex on him. The Franciscans admitted to first receiving a report of Gus Krumm’s misconduct in 1980, yet they allowed him to continue serving in Santa Barbara until 1982, and again from 1985-88.

Of the 50 total named priests, only four are still alive. Three of them — Chumik, Stephen Kain, and Josef Prochnow — held positions in Santa Barbara. Kain was named in a 2004 lawsuit for assaulting at least one student while working at St. Anthony’s Seminary in the mid-1980s. He was named again in Los Altos in 2001. Prochnow is accused of abusing minors at St. Anthony’s Seminary from 1971-1978. All three, the order claims, now live in “elder care facilities” under what it calls a Safety Plan, a sort of supervised probation for offending priests administered by the order’s internal Review Board. The order has not said where these facilities are located.

Hale said he has reason to believe at least one of them is located in a residential California neighborhood “with families nearby who have no way of knowing who these men are or the risk they pose to children.” Hale said, “The only reason the Franciscans can get away with this is because they never reported the perpetrators to law enforcement, or if they did, it was long after the criminal statute of limitations had expired.” As a result, he said, the men escaped prosecution and having to register as sex offenders. The description of an “elder care facility” may also be misleading, Hale said. “It creates the false impression that these men are in failing health and perhaps less of a threat.” But just last month, he learned, Prochnow was ministering across the street from a school. “I’d love to see the state attorney general step in and look at whether the Franciscans breached their duties as mandatory reporters,” Hale said. “It may be too late, but it’s worth an investigation.”

Hale said while the new names will help the public better understand the sheer scope of the abuse perpetrated by the Franciscans, it likely omits any information that could open them to legal liability. “This is the Franciscans protecting their own,” he said. “Their feet are being held to the fire, and that’s the only reason they’re releasing this information. But I’m confident this is not the complete story.” Now by his count, Hale said, “37 Franciscan predators have been assigned, in residence, or performed their ministry on a recurring basis in Santa Barbara.” The Franciscans dispute that number, he said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.