This week, the Santa Barbara community mourns the young people killed in the Isla Vista shooting five years ago. Like so many shootings, this deadly attack could have been prevented.

Gun violence is a deeply personal issue for both of us. Senator Feinstein, while a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, discovered her colleague Harvey Milk, after he had been shot by another supervisor. Congressmember Carbajal, at age 12, found his older sister’s body after she took her own life using a firearm.

We understand through our own experiences that there can be warning signs before someone uses a gun to harm themselves or someone else. In the Isla Vista shooting, the gunman had shown signs he was going to commit violence.

In the weeks and months leading up to the massacre, the gunman’s mother warned local law enforcement about his desire to kill those around him. He posted disturbing videos on social media, drafted a 140-page manifesto planning his deadly attack, and spent months stockpiling more than $2,000 worth of firearms and ammunition.

Despite that disturbing behavior, his family and law enforcement were powerless to keep a gun out of his hands.

Following the shooting, California passed a law that allows family members and law enforcement to ask a judge for an extreme-risk protection order, a temporary order to block dangerous individuals from purchasing a gun for 21 days and to remove any weapons they already possess. After the initial 21 days, there’s a second court hearing to determine whether the judge’s order should be extended for up to a year.

This isn’t a new idea. Federal law already has nine categories that prevent someone from obtaining a gun, including people convicted of a felony, committed to a mental-health institution, or battling drug addiction.

But current law in many states doesn’t provide any way to prevent people who show violent and disturbing behavior from buying a gun before they act.

Think about that. Even if you know a loved one is considering violence, you would have to wait for that violent act to occur before the judicial process would allow law enforcement to temporarily remove their guns. That makes no sense.

Similarly, the law doesn’t stop someone who has been abusing his or her partner from buying a gun, unless there has been a previous domestic-violence conviction.

Simply put, there is still no nationwide tool that would allow law enforcement and the courts to prevent tragedies like Isla Vista.

Congress must fix that.

That’s why we introduced the bipartisan Extreme Risk Protection Order Act, legislation that would give family members the tools necessary to keep guns out of the hands of dangerous people.

Our bill would help states enact laws so that family members could go to court and ask a judge to prevent someone who is clearly violent or intent on committing violence from buying or having a gun. It would provide a safety measure for our homes, schools, and communities, while ensuring due-process rights are protected.

California’s law has shown that extreme protection orders work. After the law was enacted, San Diego’s city attorney obtained 100 of these orders against people exhibiting a range of violent and threatening behavior, from domestic violence to stalking to threats on social media. Here in Santa Barbara, the county has issued another 21.

Those extreme protection orders recovered 169 guns, including 16 assault rifles. In one case, law enforcement seized a cache of 56 guns, explosives, and 75,000 rounds of ammunition.

Unfortunately, only a handful of states have similar laws in place. In most states, families are essentially powerless if they fear their loved ones are going to hurt themselves or others with a gun.

Using the California law as model, the Extreme Risk Protection Order Act would provide all states with the same protections — a measure that even the National Rifle Association has recently supported.

There is overwhelming public support for many commonsense gun-safety proposals like banning bump stocks, ensuring suspected terrorists cannot buy guns, and requiring universal background checks. In fact, in the last election, many pro-gun-safety candidates won big in traditionally Republican districts, including seven in California.

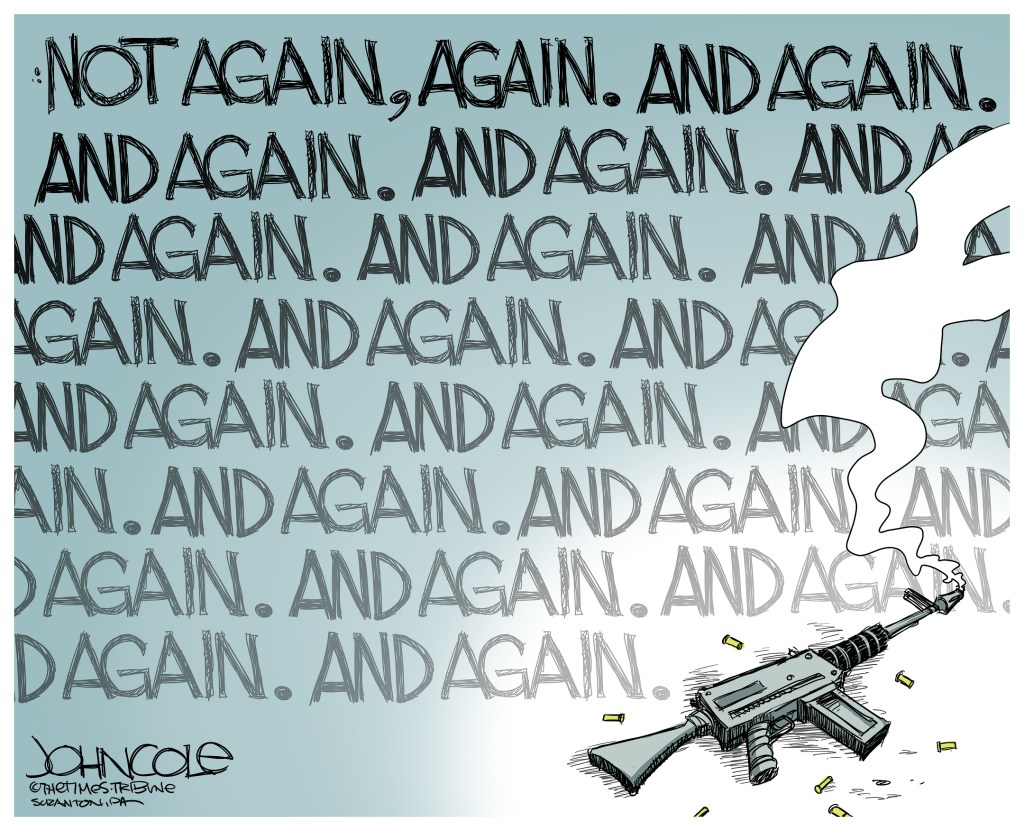

But even as we debate big ideas to stop gun violence, including a ban on assault weapons, small steps like a nationwide system of extreme risk protection orders would save lives.

This is a sensible way for Congress to make a significant change, and we hope our Republican colleagues will join us in the effort.