Whether they just want to be more knowledgeable foodies or get inspired to embark on careers as chefs, culinary journalists, or even food reformers, UCSB students can now take a class called the History of Food. The enlightening and literally appetizing course was designed about a decade ago by two Department of History professors, Lisa Jacobson and Erika Rappaport, who transformed their research on book projects into the class.

While studying the dynamics of alcoholic beverages, food shortages, and wars, it dawned upon Jacobson that these topics were so vast that they had potential to be a full quarter-long course. “Even though food is something we have every day, the class gets students to reimagine the way they see it,” explained Jacobson. “The course sets the table for thinking about questions focused on justice, access to food, hunger, reform, and the way food creates identities.”

With topics that include industrial foods, the intersections of gender and food work, and “counter-cuisines” — efforts to grow and cook natural compared to industrialized foods — students’ eyes are opened to how food is viewed across different cultures and how culinary culture evolves over time. As a student in the class last quarter, I learned that food has been the reason for the rise and fall of empires, and that it frequently dictates global trade. While food brings people together, it also tears us apart, and it is woven into the fabric of our cultural differences.

Jacobson encourages students to consider how what they eat communicates who they are — essentially, are we what we eat? Students are encouraged to incorporate their day-to-day life experiences with food into classroom discussions. We also conducted family interviews and had opportunities to cook and sample wartime recipes. Because of that, Jacobson said that the class “accounts for a higher-than-usual student participation.”

In a lesson on how food companies rebrand products to increase sales, we learned about how Campbell’s created and endorsed a tomato carrot-cake recipe to pump up their tomato soup. A fellow student baked the recipe for the class to try, which was an interesting, savory-sweet blend, to say the least.

“The course content changes each time we offer it because food history is a very vibrant field,” said Jacobson. “We are modern historians with an abundance of material to cover, and there is always new information that is uncovered.”

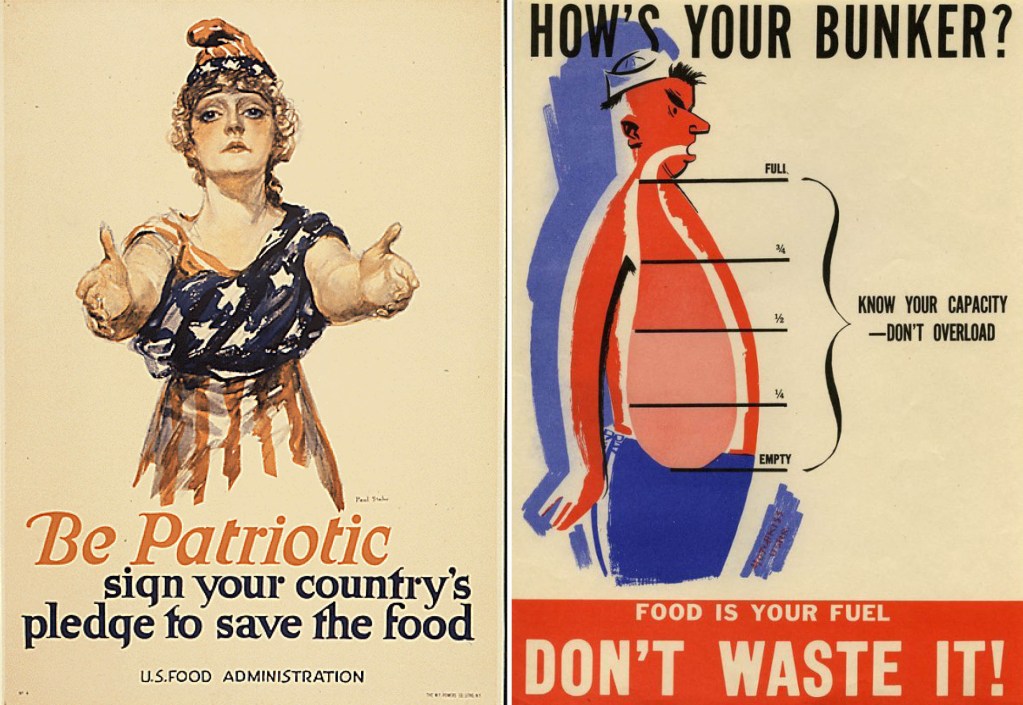

Our course mostly examined modern interactions with food, but it began with the extravagance of the Spice Trade, covered the migration of food in the post-Columbus era, and touched on legislative food reforms in the 20th century, like regulating the meat packinghouses. It then focused on our contemporary perceptions of wellness, obesity, and eating disorders.

Jacobson, who is researching a book project called Fashioning New Cultures of Drink: Alcohol’s Quest for Legitimacy After Prohibition, handles classes about how perceptions of alcoholic beverages have evolved over time, among other topics. Rappaport, who wrote the 2017 book A Thirst for Empire: How Tea Shaped the Modern World, taught us how caffeinated beverages have streamlined social change, with cafés creating hotbeds for intellectual discussions. Two of the most compelling for our class were Rappaport’s lecture on “The Caffeine Revolution” and Jacobson’s discussion of “Intoxicating Foods and Beverages.”

By exploring these topics, the “History of Food” stimulates curiosity about something so familiar as what we eat and makes us think critically about our choices. It’s a great way to learn more about something that we all do every day.